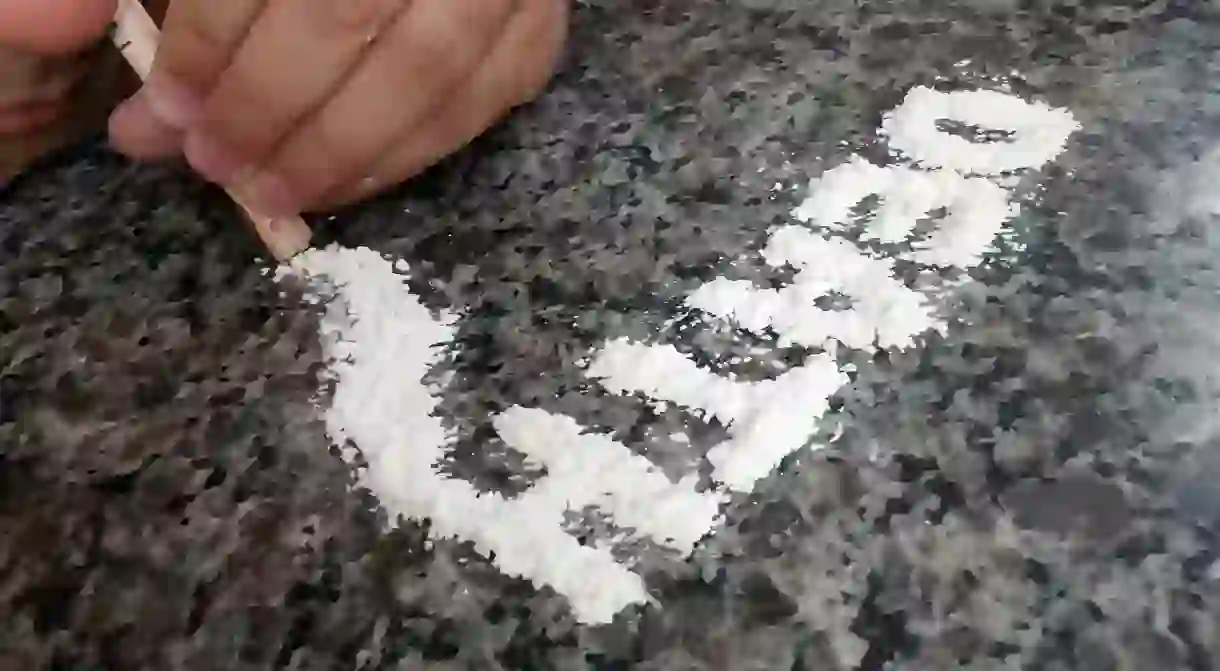

How Cocaine Tourism Is Causing Homicides in Colombia

Though Colombia is now synonymous with incredible biodiversity, world-class coffee, and life-changing travel experiences, for many the country still has strong associations with the cocaine trade. Stereotypes aside, here’s why taking cocaine as a visitor has devastating effects on far more than just body and mind.

Colombia is the highest producer of cocaine in the world, and unfortunately, many visitors see taking it as a ‘must-do’ activity on their trips to Colombia. However, there are a variety of reasons why you should avoid taking cocaine in Colombia, and not just because it could land you in jail. It’s hardly advisable to take cocaine anywhere, but Colombia, with its decades of drug-related violence, is arguably the last place you should consider taking it.

Between 1990 and 2010 there were 450,000 homicides in Colombia, with somewhere in the region of 7 million Colombians being internally displaced, a huge number of which were connected to the cocaine trade. As author Gustavo Silva Cano put it: “Cocaine has made Colombia bleed”.

Colombia’s internal conflict is incredibly complex and multifaceted. Though it is too simplistic to pin the blame for all of the violence on a single cause, many see the multi-billion dollar cocaine industry as having played a huge part in sowing terror and death in the country. The Medellin and Cali cartels, FARC guerrillas and right-wing paramilitary groups have all said to have been heavily involved in the cocaine trade, which financed weapons, bombings, military training, and terror amid ordinary Colombians.

Many people hear these shocking statistics about cocaine and comfort themselves with the thought that all of this happened a long time ago, and that drug-related violence in Colombia, particularly after its recent peace deal with the FARC, is a thing of the past. And while the country is not in the throes of extreme violence as it was back then, the death and displacement related to the drug trade continues.

With the demobilisation of the FARC, criminal groups have moved fast to take over profitable coca production areas, and the result has been a spike in displacement in rural regions. Assassinations of activists and community leaders have also increased dramatically in the past year – many leaders who dare to speak out against criminal activity in their regions face the ever-present threat of death. Once again, this is not entirely down to the cocaine trade, but it plays a huge role: the grams of cocaine sold in fancy city nightclubs might be significantly cheaper than elsewhere – and therefore an attractive option for many travellers, it seems – but it all comes from the same place, and coca-growing regions continue to be subjected to high levels of violence, displacement and murder.

Cocaine tourism represents a drop in the ocean of the international cocaine industry, which is worth somewhere in the region of $300 billion annually. However, the burgeoning drug tourism industry in the large cities of Colombia is also connected to criminal gang activity and violence. While foreigners coming to Colombia to take drugs might not have a huge impact directly, the growing local industry that they contribute to has the potential to “become a game-changer for Colombia’s drug traffickers”, and lead to increased drug-related urban violence, as drug dealers and bosses wise up to the growing market on their doorstep. Apart from the violence meted out in rural areas as a consequence of the cocaine trade, recent spikes in urban crime and murder rates are said to be linked to this growing domestic drug market.

Aside from the terrible human impact, the cocaine refining process also has a huge environmental impact: it produces more than two metric tonnes of waste per coca hectare, utilizes toxic pesticides in order to clear thousands of hectares of jungle (every cultivated hectare of coca causes the loss of around 3 hectares of forest), and creates 200 litres of contaminated water for every kilogramme of coca base produced. Seeing as most coca plantations are hidden deep in Colombia’s incredibly biodiverse jungles, this waste water normally ends up being dumped in Amazonian rivers. And then there are the toxic chemical sprays that were used for many years to target coca crops: the WHO found that glyphosate, which was sprayed over 4.3 million hectares of Colombian national territory, is very likely to be carcinogenic. The use of this chemical has been suspended, but there is strong pressure on the Colombian government from its international backers to start using it again to fight growing coca production.

Colombia as a country is not a high consumer of cocaine, contrary to the preconceptions of many visitors. However, Colombians have witnessed firsthand the damage and destruction that cocaine has wrought upon their country and, unsurprisingly, generally steer well clear of it. A 2013 study found that, although Colombian drug consumption had increased slightly since 2008, only 0.7% of the population had used cocaine within the previous year, significantly lower than similar studies in many other countries. A simple reason for avoiding using cocaine in Colombia is to avoid offending local people, many of whom see cocaine as a shameful part of their country’s past, and something they wish to move on from, or are painfully aware of the continued violence being caused by the drug trade.

There are many who argue that these devastating human and environmental impacts are the fault of the illegality of cocaine, and the dubious ‘war on drugs,’ or suggest that, in the grand scheme of things, a few travelers taking cocaine in Colombia is a small part of a huge problem. These people certainly have a point, but only to a certain extent: regardless of where it is consumed, the cocaine trade is causing devastation in rural Colombian communities, leading to displacement and violence, as well as severe environmental damage. The legalisation debate is another issue: for better or worse, cocaine remains illegal, the war on drugs limps on, and cocaine continues to devastate Colombia.

All of this might seem like another world at 3am in a hostel bar or nightclub, but if you want to visit Colombia, discover its culture, and make a positive contribution to the improvement and development of this wonderful country then don’t come here to take cocaine. Colombia has far better experiences to offer.