Julius Shulman | Defining Mid-Century Chic Though Architectural Photography

Julius Shulman is the most iconic architectural photographer of the last century. His photographs provide an eloquent narrative to the buildings he encounters and his early images redefined photography. Shulman spent his boyhood on a small farm in Connecticut and it was here that he began to contemplate the relationship between his life and the land: assessing the dialogue of buildings, the people who lived in them and the surrounding landscape. We discover more about this extraordinary artistic figure.

Shulman first gained an interest in photography at High School when taking an optional photography course. He photographed a local athletics event and the results astounded his teachers. His image of the hurdles captured the moment with beautiful composition and unanticipated clarity. After the course, Shulman abandoned photography for a few years until picking up his camera again at the University of California. Whilst at university, Shulman began to combine photography with architecture, taking photos of the old buildings that surrounded him.

After university, Shulman decided to return to his family. It was back in Los Angeles that he was introduced to the Austrian architect Richard Neutra, who later became a close friend. It was through his work for Neutra that Shulman first engaged with architectural photography as an art-form. Self-confessedly he states ‘architecture didn’t mean anything to me’, but Shulman still knew how to make a photograph work. His images for Neutra, in particular of Miller House (Palm Springs), focus on the juxtaposition between calm modernist architecture and the ancient, wild mountains behind.

Built in 1921, Hollyhock House is Frank Lloyd Wright’s first Los Angeles project. Unsurprisingly, Lloyd Wright invited the eminent Shulman to photograph his architecture. Hollyhock House famously connects the indoors to the outdoors with large, panoramic windows, rooftop terraces and courtyard gardens. This connection of building and landscape is something that resonated with Shulman, allowing him to capture the essence of the architecture.

In his ‘Exterior View of Hollyhock House’, Shulman divides the space equally between land, building and sky as if they have always belonged together. Shulman’s clever use of foliage as a framing device unites the picture and focuses the eye on Frank Lloyd Wright’s creation. The white of the architecture is echoed in the whiteness of the leaves and these elements of white appear to glow, pushing out the darkness to the peripheries of the scene. In another ‘Exterior View of Hollyhock House’, Shulman’s keen eye for the rhythms of architecture appears again. In its isolation from the rest of the house, the colonnade is less of a building and more of a pattern. The monochrome becomes a geometric play of light and dark, leading the eye into the distance. Dark plants dance upwards in imitation of the columns but with an organic sway.

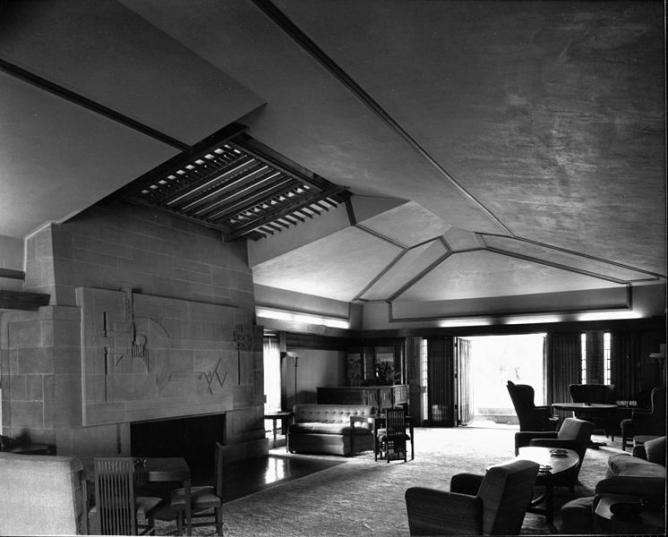

Shulman’s interior works embody an equal level of elegance. ‘Interior of Hollyhock House’, has a similar sense of rhythm. The white ceilings, pale stone and bright sunlight contrast with dark lines of coving, the black hearth and the silhouettes of curtains and wing-backed chairs. The scene is balanced in the polarity of monochrome. Despite the similarities with other works, Shulman’s interior photos have another quality: ‘Human Occupancy’. Each interior expands on the story of the outside: the images are grounded, less timeless. The human aspect gives the viewer an intimacy with the occupants, their life and the building in which they live.

Although Shulman did at times embrace colour photography, black and white always remained his favourite method of imagery. As Ted Grant states, ‘when you photograph people in colour, you photograph their clothes. But when you photograph people in black and white, you photograph their souls!’. Schulman’s colour photos depict the architecture beautifully but they do not capture the soul of the building in the same way as his monochrome works.

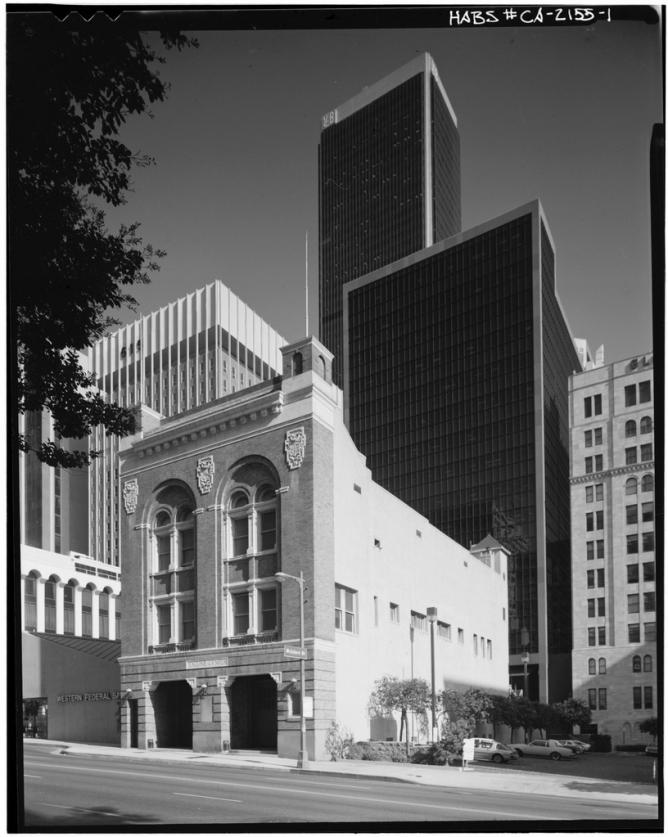

In the 1980s, Shulman photographed a variety of buildings in Los Angeles including the City Halls, a fire station and the Friday Morning Club. All are wonderful photographs, but Los Angeles Fire Station really embodies Shulman’s style. The dichotomy of light and dark is again included, with the smaller white buildings offset by a dark, looming skyscraper behind and a black tree in the foreground. The contrast does not end at colour – in this instance, Shulman has chosen to record architecture of the old and new. There is an interplay of different historic periods and perhaps this image in particular reflects Shulman’s career. The old-buildings of his university days are now eclipsed by his Modernist works. Nevertheless, the decision of an eminent, mid-century photographer to focus on this timeworn fire station displays a reverence for this classic architecture and a respect for his roots as a photographer. As Shulman changed, his subjects changed.

Shulman’s vast portfolio of work has influenced many contemporary architectural photographers such as Daniel Hewitt, Simona Panzironi and especially Los Angeles based Moby. These photographers continue Shulman’s legacy of black and white photography, rhythmic composition and capturing something of the soul of the buildings they work with.

For Shulman ‘a photograph is a design in which you assemble thoughts in your mind’. Composition is intrinsic to Shulman’s works – it makes the difference between a work being purely photography and it becoming a piece of art. Throughout his life, Shulman transformed architectural photography by considering not just the building, but the life it contained. Shulman captures the life of the architecture, its relationship to surroundings and the people who inhabit it.

In 2015, Hollyhock House will be open to visitors after a period of restoration: Hollyhock House, 4800 Hollywood Blvd, Los Angeles, CA, USA, +1 323-644-6269

By Tamsin Nicholson