Gauguin's Tahiti: A Creative Obsession

Gauguin’s travels to French Polynesia have been well documented, and the artist entered a new phase of both his personal and artistic career after arriving to Tahiti for the first time. Whilst improving his creative output and altering his painterly style, he allowed life in Tahiti to alienate him from Europe, and became absorbed within the hypnagogic world of his paintings.

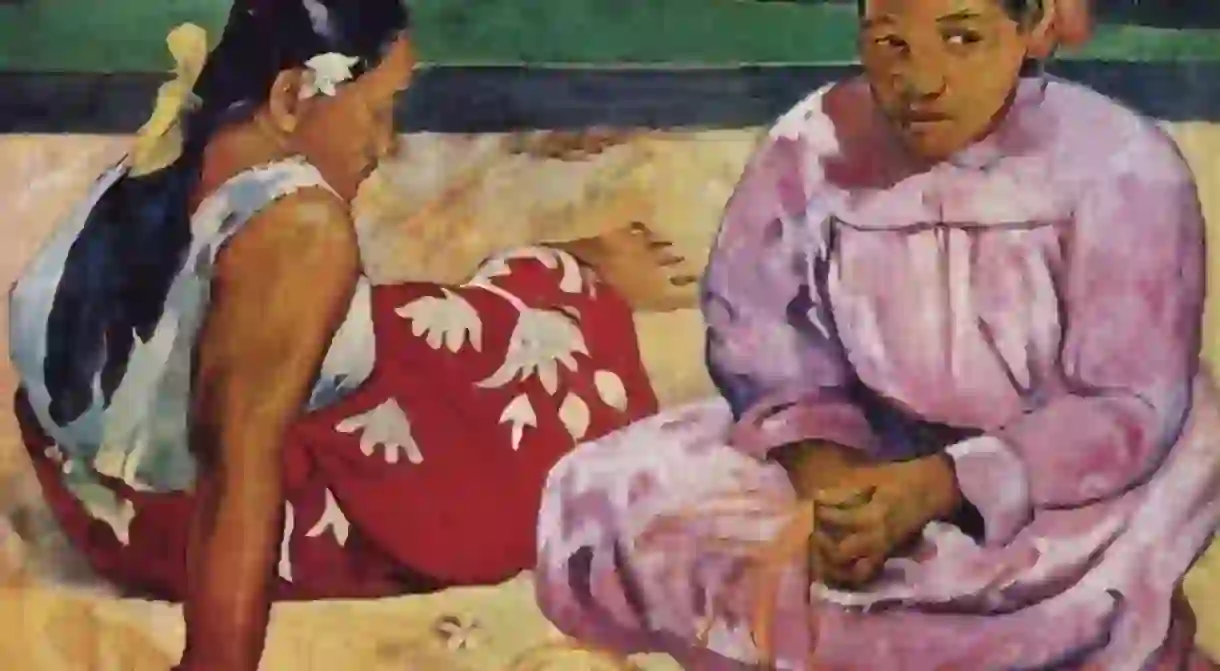

Due to various problems in his personal and professional life such as concerns over his popularity as an artist, struggling to make enough money, and lacking in aesthetic inspirations, Gauguin travelled to Tahiti in 1891, leaving his old life and family behind. It is believed that he thought that a journey to an exciting and alledgedly exotic foreign land would bring about a new era in his life, and refresh his artistic career as a painter. This certainly did happen, at least with regards to his painting style, and works by Gauguin from this time in his life move from his previous impressionistic style and the teachings of Pissarro towards having more Primitive characteristics. The colours become more vivid and the shapes bolder and more graphic, whilst his subject matter turns gradually towards the Tahitian women of the island, often getting on with menial, everyday tasks, sometimes carrying solemn expressions.

Gauguin became obsessed with Tahiti, and the ways in which it was effecting him. It can be seen to have represented a sort of refugium peccatorum for him, and it was undoubtedly full of temptations and novelties. The scenes of Tahiti gave his paintings stronger peculiarities, and in addition to an influence from his female subjects, the painter took great influences from the nature that suddenly surrounded him, giving him a newborn affection for life. In his journal ‘Noa Noa’, Gauguin outlines his experiences of life in Tahiti with fantastical images and great descriptive writing, the extremities of which have been disputed by literary critics as fraudulent hyperbolic claims of primitivity and eroticism in a place that was relatively Westernised by the time Gauguin arrived. The area of Papeete, where Gauguin initially chose to settle, was already occupied by a number of settlers from Europe, and so Gauguin was not as immersed in exotic primitivism as his contemporaries often thought.

Although Gauguin’s surroundings were not as untamed as perhaps he would have liked, the theme of nature and the natural beauty of the human body in his works is important. Whilst he reportedly referred to Tahitians as “fool” and “meek”, causing many critics to accuse him of having excessively bourgeois tendencies and a colonial attitude, he was moved by their culture and art in one way or another. The works of Primitivism that he came across on Tahiti directly influenced his painting, whether his agenda was to intrigue overseas audiences, or to capture the beauty of the Tahitian women and their surroundings is still in dispute. Over time however, Gauguin did begin to adopt the culture and belief systems of the Tahitians, and gradually rejected the missionary teachings of Catholicism, blaming them for the disappearance of many Tahitian works of art.

Old Polynesian myths tell that minerals, plants, animals and men all share the same roots and consistency. This exotic interpretation of what Ancient Greeks more or less referred to as atomism, has been reshaped as a modern quest in a number of different areas of research. It is possible that nature has never really been far from Polynesian social and cultural life, but the shift in Gauguin’s painterly style and personal attitude can be seen to express not only the importance and beauty of nature, but its fundamental role in inspiring scientific discoveries and artistic efforts. The story of Gauguin’s later life and its eventual end is fairly dejected, with his abandonment of Europe came an alienation from the people there, and the slump in sales of his paintings did not recover in his lifetime.