Gyre: The Plastic Ocean Trashes LA

The USC Fisher Museum is full of garbage. Colorful bits of plastic have traveled over land and sea— bought, sold, discarded, collected, cataloged, and remixed into art. No, it’s not a prank you’re not in on. It’s Gyre: The Plastic Ocean, an activist art exhibition in which 25 international artists create art from found trash while raising awareness about its impact on oceans and wildlife.

On view through November 21, 2015, the show is an aesthetic maelstrom, well worth wading through.

An ocean gyre is a massive whirlpool made up of networks of currents, encouraged by wind and the earth’s rotation. There are five major gyres in the world’s oceans, which accumulate massive quantities of marine debris — the vast majority of which is plastic. The North Pacific Gyre, home to the notorious Great Pacific Garbage Patch, spans an area roughly twice the size of the United States. It is the largest ecosystem on Earth, where plastic is commonly mistaken for food by sea creatures and seabirds, causing serious health problems and death.

Many of the works in Gyre take trash out of the ocean and into the gallery to confront the public. ‘These plastic objects are coming back to haunt us,’ Pam Longobardi says of her Drifter’s Project. The artist is one of the chief orchestrators of the exhibition, which is a continuation of a project that began as a data-gathering and cleanup expedition of artists, scientists, and policymakers along the Alaskan coastline in 2013. On the trip, Longobardi collected thousands of pieces of garbage that now comprise her work, ‘Bounty Pilfered,’ an enormous black cornucopia of found detritus in the museum’s main gallery. The piece is jarring, offering up a gluttony of Technicolor garbage as if saying, ‘Eat this.’ It’s no coincidence that the piece shares initials with British Petroleum — for her, the memory of the 2010 Gulf oil spill looms large. According to her, ‘this work is evidence, testimony of a crime against nature.’

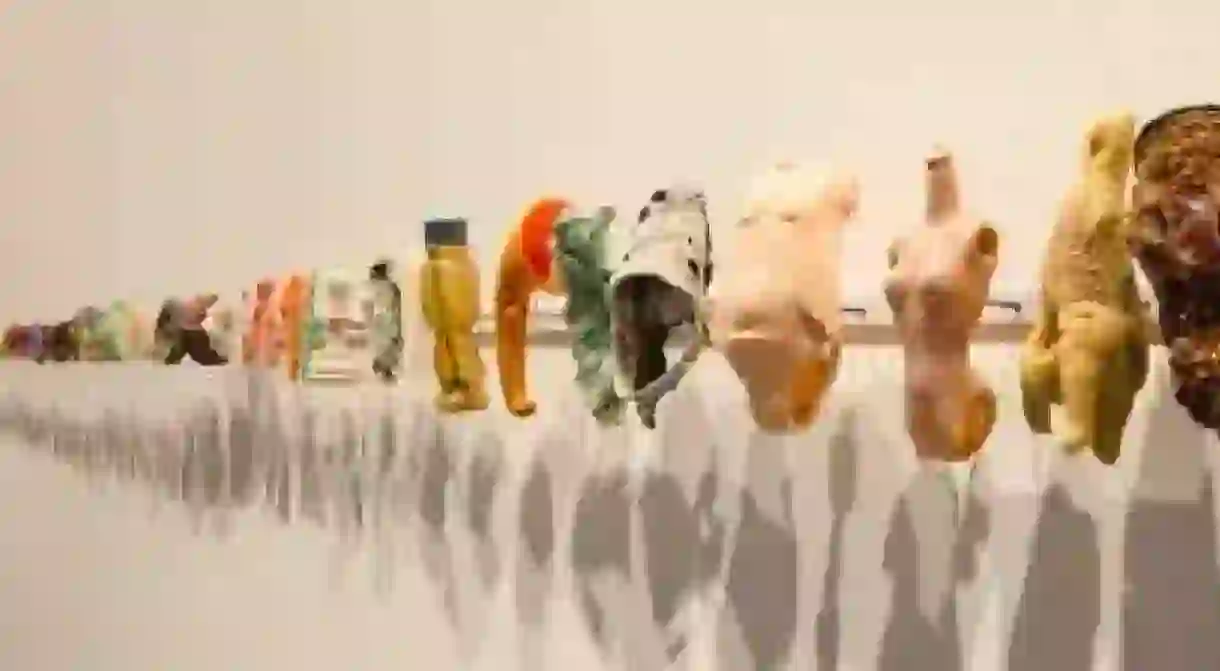

For her piece ‘Economies of Scale,’ the artist displays pieces of found plastic in a linear-scale progression across the gallery wall. Starting with a single bead of styrofoam, the pieces get incrementally larger ending with a distorted piece of plastic that bears a disturbing likeness to a human skull. Like a swath of hieroglyphics, the eroded toys and familiar household objects play off of each other to imply a poetic narrative, part whimsical part foreboding. ‘To me, these are messages — the ocean is communicating with these materials and I am translating it into forms that other people can see,’ she explains. Longobardi considers her work part of the cultural archeology of our time. Gesturing toward the bits of trash on the wall she says, ‘These will be the future fossils that archeologists find. It’s already part of the geology.’

Like many of the other artists in the exhibition, Longobardi is an activist in equal measure, and her work often takes her outside of traditional gallery spaces. In collaboration with Plastic Pollution Coalition CEO Dianna Cohen, she’s creating a model sustainable society through the Plastic Free Island Project in Kefalonia, Greece. At the show’s opening, I find Cohen among a group of rapt listeners as she describes a cleanup project in Greece: ‘Drinking espresso on the shore in Asos one morning, we spotted a sea cave and decided to swim to it. We swam in through a sea entrance in the cove, which was really like the Pirates of the Caribbean,’ Cohen recounts romantically. ‘It was lit a little bit from the light coming in from outside, and as our eyes adjusted, we looked up. It looked like it was full of colored treasure. But it was really plastic garbage.’

Cohen is at the helm of Plastic Pollution Coalition, a nonprofit working to stop plastic pollution through initiatives to measurably reduce it and educate the public about its toxic impact. She is also a practicing artist, working with plastic bags as her primary material for the past 25 years. Her piece, ‘Owl Real,’ is a collage of single-use plastic bags, sewn together to form a patchwork poem of words, logos, shape and color. ‘Plastic represents the future and technology and all of the best of humankind,’ she explains. ‘But too many plastic objects are designed with an intended obsolescence. It’s an irresponsible use of a valuable material that is now polluting our world and affecting our health.’ She hopes that her artwork spurns a significant shift in consumer attitudes towards more sustainable choices, beginning with just saying no to single-use plastic products such as bags and bottles.

Across the gallery, the glowing figures of Cynthia Minet’s ‘Pack Dogs’ beckon. The life-size model huskies are constructed entirely of discarded plastics, internally illuminated like the northern lights of Alaska. The piece is part of the artist’s Unsustainable Creatures series, which continues in the adjoining gallery with an enormous red elephant and two hawks suspended in a tumbling mating ritual. Minet is quick to confirm that the unsustainable creatures are, in fact, us. ‘These animals are stand-ins for humans and represent our total dependence on plastics, petrochemicals, and electricity,’ she explains. ‘We are chained in the same way that domesticated animals are working for us.’ A Los Angeles local, Minet isn’t afraid to get her hands dirty and frequently dumpster dives near her studio at the Brewery Arts Complex to source her sculpting materials.

As a whole, the diverse works in Gyre are as beautiful as they are haunting. Having trashed the place, the viewer is surrounded by the willful neglect of our throwaway society. A walk through the exhibition is guaranteed to inspire even the most callous viewer to take pause and wonder how things might be different and what we can do to change for the better.

By Marnie Sehayek