The Story of Oscar Wilde in America

A quote attributed to Oscar Wilde has the famous aesthete remarking that America is “the only country that went from barbarism to decadence without civilization in between.” And yet, when Wilde arrived in New York in January of 1882 for a 150-city tour at the age of 27, both the playwright and the country were in rare form.

In Leadville, Colorado, he outdrank miners, gave talks on art and fashion to the likes of Springfield, Massachusetts (where he scandalized the local paper, which parodied him in a piece titled “Unmanly Maness”), and in New Jersey hobnobbed with Walt Whitman, who plied him with elderberry wine.

At the time that he arrived in America, Oscar Wilde (born Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde) had his greatest successes still ahead of him. He had not yet achieved literary fame with The Portrait of Dorian Grey (which includes the exchange “When good Americans die, they go to Paris.” “Where do bad Americans go?” “They stay in America.”), nor had he thrilled audiences with The Importance of Being Earnest. Above all, it was well before he would be tried and convicted for “gross indecency” in 1895. Instead, the Wilde that Americans met in the year-long tour—which was extended due to record ticket sales—was a striking, eloquent, composed, and idiosyncratic young lecturer, who made his impression on the young country well before famous-for-the-sake-of-being-famous celebrities were the norm.

In fact, Wilde in 1882 was more famous as the target of a parody by W.S. Gilbert, whose operetta Patience featured the Wilde-like “grandiose boob” Bunthorp. The fictional Bunthrop became a sensation in London, but Gilbert and Sullivan, who were managing the play on Broadway, worried that Americans would be left out of the joke without the example of Wilde. So, their producer convinced Wilde to come to the U.S. wearing his most outrageous Bunthorp-like costumes (including a coat in the likeness of a cello). Everyone expected Wilde to scandalize the crude Americans he was invited to perform for; instead, they embraced him. In turn, Wilde walked away with a different impression of the country while remaining characteristically wry, stating that “America has never quite forgiven Europe for having been discovered somewhat earlier in history than itself.”

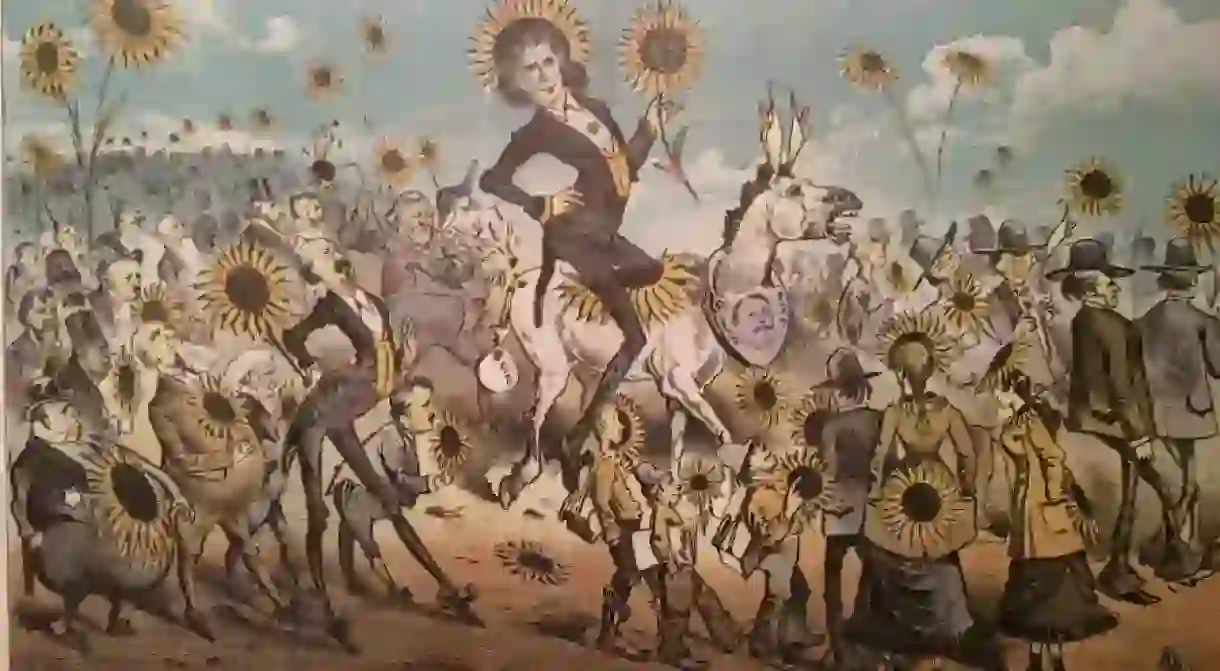

As much remarked upon, Wilde’s essential curiosity and kindness meant that he was as interested in the country’s farmers and cowboys as in its well-connected writers, wits, and politicians. In fact, his presence in America was so deeply felt that the image of Wilde created after he sat with a famous U.S. portraitist soon made its way into ads for cigars, tonics, and even quack medicine (which was also enjoying a vogue in the States at the time). When reporters arrived at Wilde’s hotel rooms, they found it set-dressed with lilies and sunflowers, with the sofas wrapped in animal skins—and at the center, ever-becoming Irish-born Wilde himself. Without fail, journalists would come expecting a self-mockery of a man, an erudite and condescending European. Instead, they found the young Wilde charming and unfailing in hospitality, leading one San Antonio writer to declare that “We can recall nothing to ridicule, even though we were so disposed,” and urged his readers to yield to Wilde’s invective to instill “in the minds of our rising youth a love of the beautiful.” For his part, Wilde remained impressed by the potential he found everywhere in America, resulting in the famous line in his later play Lady Windemere’s Fan that “The youth of America is their oldest tradition. It has been going on now for three hundred years.”