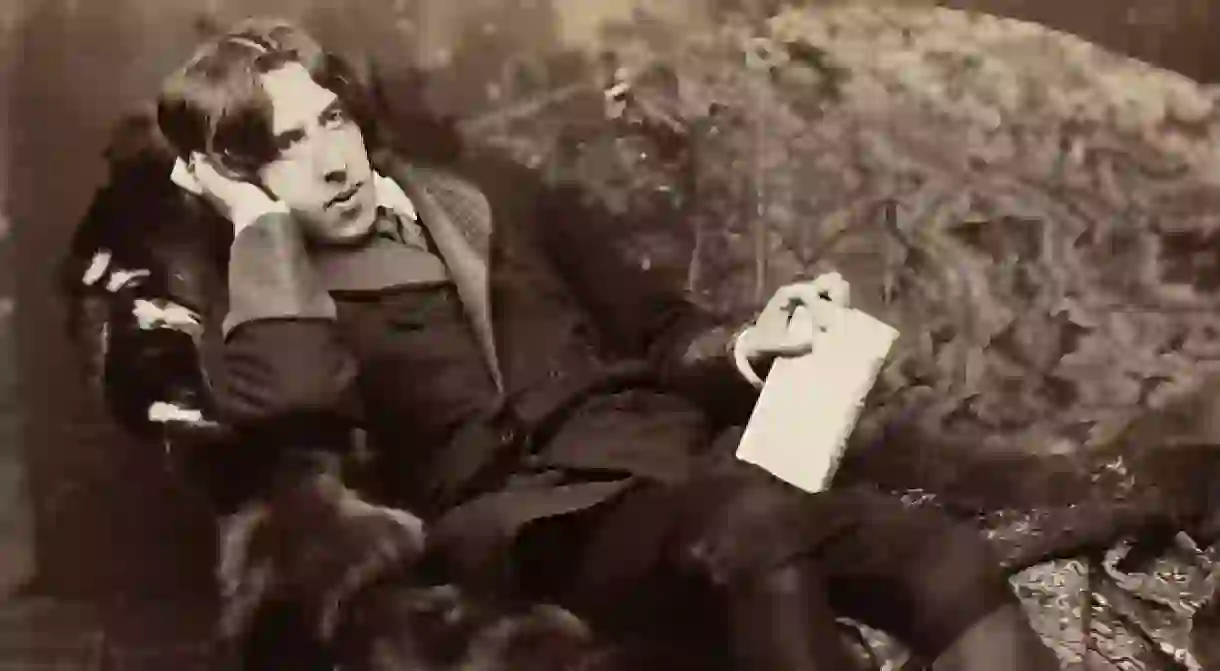

An Introduction To The Genius Of Oscar Wilde In 8 Quotes

Incomparable may be too nice a compliment to reserve for anyone, but it certainly isn’t a word wasted on Oscar Wilde. Rare are the writers who have influenced culture, let alone literature, quite to the extent that he has. What makes him so special, you ask (no doubt annoyed, as you should be, by all this praise)? Well, that would depend on who you’re talking to. There are three Oscar Wildes: the wit, famed raconteur and comedic playwright behind The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband; the tragedian, whose own life ended in misery and gave us such moral works as De Profundis, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and Salomé (the last best served in Strauss’ operatic version); and the thinker, who theorized surprisingly thorough aesthetic and political philosophies in Intentions and ‘The Soul of Man under Socialism’. So, which one do you like best?

From ‘The Portrait of Mr W. H.’ (1889)

Art, even the art of fullest scope and widest vision, can never really show us the external world. All that it shows us is our own soul, the one world of which we have any real cognizance. And the soul itself, the soul of each one of us, is to each one of us a mystery. It hides in the dark and broods, and consciousness cannot tell us of its workings. Consciousness, indeed, is quite inadequate to explain the contents of personality. It is Art, and Art only, that reveals us to ourselves.

This passage is taken from ‘The Portrait of Mr W. H.‘, a story first published in 1889, in which an attempt is made to discover the identity of the dedicatee of Shakespeare’s sonnets (who is only known by his initials, W. H.). Besides exposing a particularly intriguing theory – that the sonnets are for Willie Hughes, a male actor who specialized in playing female roles – the work also serves to impart some of Wilde’s aesthetic philosophy. We understand, thanks to him, that art is the only way we have of communicating emotions. Why? Because that’s its point; art is expression.

From The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890)

‘You like every one; that is to say, you are indifferent to every one.’

‘How horribly unjust of you! […] I make a great difference between people. I choose my friends for their good looks, my acquaintances for their good characters, and my enemies for their good intellects. A man cannot be too careful in the choice of his enemies. I have not got one who is a fool. They are all men of some intellectual power, and consequently they all appreciate me.’

Oscar Wilde’s claim to worldwide fame has perhaps more to do nowadays with The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) than with anything else. While the work is a dark, gothic masterpiece of a novel, the divine dandy couldn’t help inserting himself inside the story. Lord Henry Wotton, certainly the most entertaining character, is an immoral wit who provides many a dinner scene with necessary bon mots. Yet, not unlike Wilde’s, his wordplay should by no means be taken too lightly; it is always used to expose some truth or other, and ends up unwittingly providing the book with a moral framework. Wotton’s the reply, of course.

From ‘The Critic as Artist’ (1891)

More difficult to do a thing than to talk about it? Not at all. That is a gross popular error. It is very much more difficult to talk about a thing than to do it. In the sphere of actual life that is of course obvious. Anybody can make history. Only a great man can write it. There is no mode of action, no form of emotion, that we do not share with the lower animals. It is only by language that we rise above them, or above each other – by language, which is the parent, not the child, of thought.

Nowhere is Oscar Wilde’s aesthetic theory expanded upon quite so much as in ‘The Critic as Artist‘, an essay published in 1891. Besides doing away with the distinction between art and criticism (by the now rather obvious, and key, claim that all art depends on the critical faculty), it allows him to make a very important point on the primacy of language. His typical contrarian wit – “it is very much more difficult to talk about a thing than to do it” – leads into a statement that linguists today will surely recognize: thought is the product of language.

From ‘The Soul of Man under Socialism’ (1891)

It is clear, then, that no Authoritarian Socialism will do. […] It is to be regretted that a portion of our community should be practically in slavery, but to propose to solve the problem by enslaving the entire community is childish. Every man must be left quite free to choose his own work. No form of compulsion must be exercised over him. If there is, his work will not be good for him, will not be good in itself, and will not be good for others. And by work I simply mean activity of any kind.

‘The Soul of Man under Socialism‘ (1891) was the essay in which Oscar Wilde developed his political position. As expected of such a devoted social satirist, he proved a virulent critic of capitalism – and particularly of charity, which he correctly saw as contributing to, and not alleviating, poverty. The brand of socialism he embraced was nonetheless very different from mainstream radical positions, in that he recognized the importance of individualism – the need for people to be given the chance to do what they want.

From ‘The Soul of Man under Socialism’ (1891)

There are three kinds of despots. There is the despot who tyrannizes over the body. There is the despot who tyrannizes over the soul. There is the despot who tyrannizes over soul and body alike. The first is called the Prince. The second is called the Pope. The third is called the People.

Another quote taken from ‘The Soul of Man under Socialism’, this aphorism highlights, with particular precision, Wilde’s mistrust of the society in which he lives. While the laws of the state are what he aims to get away from, and religious morality is what he doesn’t recognize, it is the power of the people he nonetheless fears most. A prescient thought, since his downfall in 1895 was the result of a very public and politicized prosecution against his homosexuality – or what was known back then as ‘gross indecency’.

From ‘Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young’ (1894)

In all unimportant matters, style, not sincerity, is the essential. In all important matters, style, not sincerity, is the essential.

‘Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young‘ was a short collection of aphorisms first published in a magazine called Chameleon in December 1894. An exemplary concentration of Oscar Wilde’s renowned wit, Phrases isn’t exactly meant to be taken at face value. As the example above can attest, the reader finds the dandy at his most, well, Wildean, mixing delightful nonsense (exhibit b: “Wickedness is a myth invented by good people to account for the curious attractiveness of others”) with bits of aesthetic philosophy. Style, not sincerity, is, of course, the essential in all manners relating to art; in that regard, it is worth adding that Phrases certainly counts as a work of art.

From The Importance of Being Earnest (1895)

Lady Bracknell

[…] Are your parents living?

Jack

I have lost both my parents.

Lady Bracknell

To lose one parent, Mr. Worthing, may be regarded as misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.

The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People is perhaps Oscar Wilde’s greatest play, and without a doubt his most popular. Its opening night in February 1895 was a triumph from which the writer never recovered: a mere 15 weeks later, after three damaging trials, Oscar Wilde would be sent to prison on charges of gross indecency (in matters unrelated to this work, one should add). A satire on Victorian morality, the play itself makes the best case for Wilde’s comedic genius, blending farce and witty dialogue in a story ostensibly about not much at all. And if Seinfeld ever taught us anything, it’s that shows about nothing are usually the funniest.

From De Profundis (1897)

All trials are trials for one’s life, just as all sentences are sentences of death; and three times have I been tried. The first time I left the box to be arrested, the second time to be led back to the house of detention, the third time to pass into a prison for two years. Society, as we have constituted it, will have no place for me, has none to offer; but Nature, whose sweet rains fall on unjust and just alike, will have clefts in the rocks where I may hide, and secret valleys in whose silence I may weep undisturbed. She will hang the night with stars so that I may walk abroad in the darkness without stumbling, and send the wind over my footprints so that none may track me to my hurt: she will cleanse me in great waters, and with bitter herbs make me whole.

Oscar Wilde died, broke and lonely, on November 30, 1900, at the age of 46, of an illness related to an injury received at Reading Gaol (the prison in which he was interned from 1895 to 1897). While there, he managed to write a 55,000-word letter to his former lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, in which he accuses him of indifference, before delineating his spiritual redemption (in the face of injustice, as he makes sure to point out). The paragraph above is the letter’s very last, the bittersweet realization that his life will never be what it once was. He exiled himself to France upon his release, never to go back to England again.