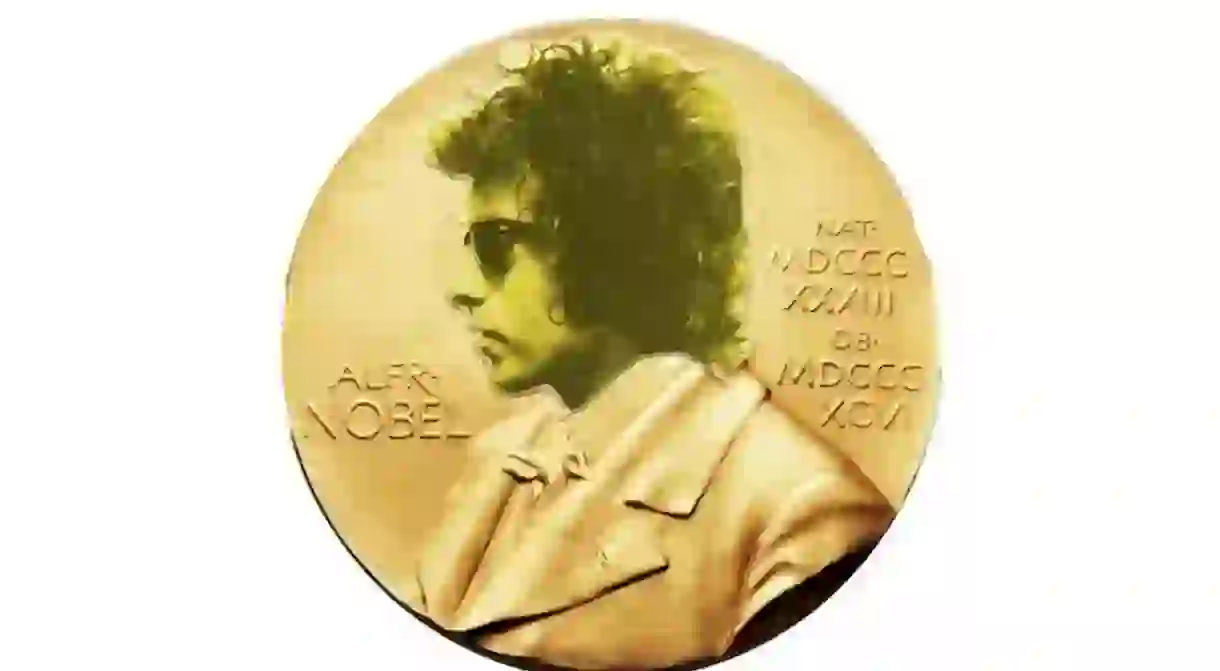

Should Bob Dylan Have Won The Nobel Prize in Literature? Two Contrasting Views

This morning, the Swedish Academy awarded its last Nobel medal for 2016, the prize for excellence in the field of literature. The selection is always met with baited breath by the literary community and for good reason: the committee isn’t shy about making snubs or stirring controversy. This year’s selection touched upon both when the committee chose Bob Dylan to be the recipient, thereby redefining what can be considered literary achievement. Our two literary editors debate on the deservedness and detriments of Dylan’s win.

THE DEFENSE

It should be remarked, first and foremost, that Bob Dylan isn’t exactly the first musician to be made laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature. That honor belongs to Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, winner in 1913, whose reported 2,230 folk songs (known as the Rabindra Sangeet) form an important facet of his oeuvre, to the extent that they are now considered foundational to Bengali culture.

Still, Tagore was awarded the prize mainly for his poetry, and in particular his own English translation of Gitanjali (1910) — which, replete as it is with verses like “Rest belongs to the work as eyelids to the eyes”, doesn’t quite make a strong case for Nobel literary taste… but never mind. Bob Dylan, then, may certainly be the first person rewarded for his musical output, but there again, the Swedish Academy has clearly chosen to judge his songwriting as one would poetry. In their words, he was rewarded “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”. In that they are not wrong.

One could go to great lengths to prove that poetry is, at its core, an art of performance, whose origins are largely undifferentiated from music, but I’m sure the reader will already be familiar with the connection (it is that obvious). In any case the names dropped here and there in favor of the decision — Orpheus, Faiz, Homer, Sappho, etc… — illustrate the point well enough.

His lyrics appeal, aesthetically, in exactly the same manner as otherwise ‘straight’ poetry, and belong to the same art form (that is, you guessed, poetry). If the two happen to differ in the way they work with rhythm — lyrics adopt the rhythm of their backing track, whereas ‘straight’ poetry creates its own using the words’ very sound — the emotion they conjure comes from the same two sources: the intrinsic music of their language, and the narratives developed by it. In that regard Dylan’s art is undoubtedly poetic, and almost unparalleled in its ability to set a scene. He is, like Nick Cave, a storyteller of the old sort, a narrative poet. To give an example from ‘One More Cup of Coffee‘:

Your breath is sweet

Your eyes are like two jewels in the sky

Your back is straight, your hair is smooth

On the pillow where you lie

But I don’t sense affection

No gratitude or love

Your loyalty is not to me

But to the stars above

[…]

He oversees his kingdom

So no stranger does intrude

His voice it trembles as he calls out

For another plate of food

While there are, arguably, more gifted wordsmiths than Bob Dylan, even where music is involved (one can think of Morrissey, or even the late great David Bowie), none have proved to be quite as highly regarded. And that’s where knowing what the Nobel Prize truly stands for is crucial. The Swedish Academy, troubled to interpret the vague words of their founder Alfred — who wished to reward those who produced “the most outstanding work in an ideal direction” — have never really cared about literary artistry… just about the writer’s general importance. How else can one explain the prizes given to the likes of Sartre, Russell, Churchill and Bergson? None were literary writers, and their contributions to letters weren’t judged for their artistic merit. Bob Dylan, then, being without doubt the most influential and widely revered musical poet, fully deserves it. It is, after all, in keeping with Academy tradition.

—Simon Leser

***

THE DISSENT

If you’re a baby boomer or a certain kind of musicophile, Bob Dylan is sacrosanct, embodying the oft-used cliché “voice of a generation.” Perhaps the phrase originated with the acclaim of Dylan’s early protest-era albums. Largely based on the body of work he composed during the 1960s, the accolades accrued by the songwriter and memoirist have become mountainous — numerous Hall of Fame inductions, 11 Grammys, a Golden Globe, an Oscar, a Pulitzer, a Legion of Honor, a Presidential Medal of Freedom, and, at various times, a number of Guinness World Records.

So what’s the point of giving even more recognition to one of the most recognized artists in the world? The Swedish Academy cited its choice of Dylan as a Laureate for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Dylan’s bard-like lyricism can’t be argued, but rewarding it with literature’s highest award is troublesome. For one thing, if he were to be judged on his writing merit alone, he certainly wouldn’t have been a contender. Aside from published collections of his lyrics, there are only two literary works to his name. The unfinished Chronicles memoir, and his 1971 off-beat poetry collection Tarantula, a line of which topped Spin’s ‘Top Unintelligible Sentences from Books Written by Rock Stars’: “Now’s not the time to get silly, so wear your big boots and jump on the garbage clowns.”

By awarding him another medal for his trophy case, the Nobel has undermined its mission to bring undue recognition to a writer, dramatist, or poet, and elevate a body of written work that might otherwise fall into obscurity. In recent years as well, regardless of how known / unknown a writer has been, the award hasn’t just benefitted a writer, but his or her publisher as well, especially small independent ones who have labored tirelessly to build writers an audience, many of whom aren’t household American names. In fact, part of the joy of the Nobel lies in discovering a writer because they have been recognized. For them, and for all, the Nobel isn’t just a dream, it’s the summit of a career spent in decades climbing, and a recognition for an artform that doesn’t always amount to financial stability, regardless of the honors. Prestige doesn’t always pay.

But this is beside the point. I’m all for expanding the notion of what should be considered literary, as I supported the award given to narrative journalist Svetlana Alexievich, but this decision feels like a ploy. A way to jazz up the awards by bringing the Nobel to a level of populism that serves no higher purpose than to give the award a bigger splash in the media. It’s doubtful that Dylan has read or heard of many of the other contenders. He doesn’t engage with the literary community, nor does he seem to champion anyone who isn’t dead. This just isn’t his scene. Nobody but Dylan and his millions of fans will benefit from his being a Laureate. Literature certainly won’t. And if the Nobel committee is going to open its doors to anything that includes written words, who else gets to qualify and at what cost? As writer Hari Kunzru tweeted: “If they don’t give the Nobel to Kendrick in 2030 there will be trouble.”

—Michael Barron