How Nick Cave's Lyrical Genius Sets Him Apart From Other Songwriters

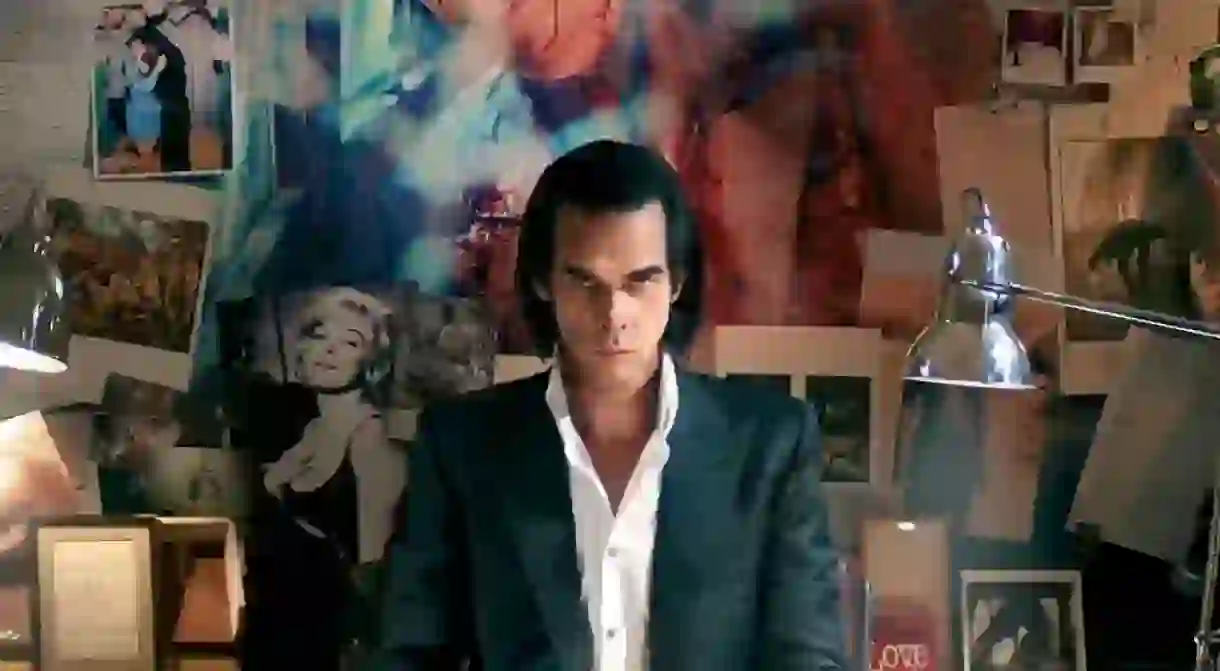

Performer, pianist, guitarist, novelist, screenwriter… there is more than one Nick Cave. To celebrate the release of the Bad Seeds’ newest album, Skeleton Tree, and documentary, One More Time with Feeling, we take a look at what makes the man such a unique artist: the writing.

Even the most ardent Nick Cave fan will acknowledge it’s not particularly easy to fall in love with his music. Whether it’s Cave’s voice — groaning, a bit off, (the man himself has admitted it wasn’t very likeable) — or the general darkness of his output, it’s the kind of charm that takes a while to crystallize, especially for the uninitiated. Yet charm it certainly has, and it’s not all about his magnetic personality, either. Make no mistake: writing is what sets Cave apart from other rock stars, and lyrical sensibility is, more than the music itself, the dominant feature of his artistic work.

If anything, 20,000 Days on Earth — the partly-fictionalized documentary Nick Cave released in 2014 — makes clear that his creative process is centered on the typewriter. As the camera follows him working on his last album, we get a glimpse of just how fundamentally his words instruct the compositions. “Songwriting is about counterpoint’ he admits in the film, ‘counterpoint is the key: putting two disparate images beside each other and seeing which way the sparks fly. Like letting a small child in the same room as, I don’t know, a Mongolian psychopath or something, and just sitting back, and seeing what happens. Then you send in a clown, say, on a tricycle, and again you wait, and you watch… and if that doesn’t do it: you shoot the clown”.

Nick Cave is a storyteller of the old sort — not a poet in the way we’ve come to know them, but a raconteur who edges closer to spoken word, a theatrical wordsmith with a taste for the grim and the sordid. His songs are unique in the music world because they manage to create scenes, scenarios of uncommon depth. If his sound has evolved along with the times — from the post-punk of 1980s Berlin to the experimental alternative of today’s Brighton — the frontman’s overall method has remained unchanged. Consider ‘Higgs Boson Blues’, from Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ last album, Push the Sky Away (2013):

Though this number’s particular musical style is, of course, very much in keeping with sleek modern production, the songwriting itself has been a constant in Cave’s career. Built upon an easy, repetitive, if sonically intricate accompaniment (courtesy of the ever so talented Bad Seeds), it puts the man’s linguistic talents on a pedestal. And while like all his pieces this one relies on little more than two or three-chord structures, the lyrics themselves are remarkably elaborate. This particular example may be more narratively nebulous than his usual works, but it still tells a dark tale: what is the Higgs Boson Blues? It’s the melancholy of progress, the howls of the left behind, of those finished by the future. Interspersed with the Higgs Boson’s discovery is a wealth of historical allusions: Robert Johnson’s mythical pact with the devil, Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder, the medieval Jewish hat, New World missionaries, Hannah Montana (presumably because, you know, Miley Cyrus killed her off by growing up… or something), etc…

This is Nick Cave at his best, recognizable by its intricate orchestration and vivid storytelling, a trope which has endured multiple genres and line-up changes. As the Bad Seeds, led by multi-instrumentalist virtuoso Warren Ellis, have kept refining their output, the songwriting itself has remained as baroque it’s ever been. It is what defines the swagger-and-grime of ‘Stagger Lee’, the haunting ‘Do You Love Me? (Part 2)’, the hopeless grandeur of ‘Jubilee Street’, and the seedy adventures of ‘Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!’. No other artist sets down a track in quite the same way:

“Our myxomatoid kids spraddle the streets, we’ve shunned them from the greasy-grind

The poor little things, they look so sad and old as they mount us from behind

I ask them to desist and to refrain

And then we call upon the author to explain”

Not one to be confined by format, Nick Cave has also penned two novels, And the Ass Saw the Angel (1989) and The Death of Bunny Munro (2009). The former, completed while the musician was still a mildly paranoid Berlin junkie, is the epitome of what makes Cave, well, Cave. Crammed full of verbose sentences and country drawl, it presents a plot replete with gore, delusion, and biblical references (the author likes to endow his tales with an evident higher being, despite being himself a non-believer. His rationale, like Nabokov’s, is that these worlds actually do have their creator). Euchrid Eucrow, a lonely mute born into a cast-out, violent family, lives out his days in a Southern valley run by religious fanatics, preparing his revenge on all those who hurt him, while the world around him is affected by dramatic supernatural events. But don’t worry about the what, worry about the how! Switching between first person and third person narration, Cave writes in a rhythmic prose far removed from the banalities of Southern Gothic. Here he is describing an eerie tree:

“In the numb gesture of this ever-dead, a pair of pinguid crows hopped, foot to foot, along one pleading limb, like two conspiring nuns cackling and pecking and flapping into the air, to hover a moment and then alight once again, to hop and squawk at the foot of the murmurous crop. Like the ants, the rogue crows seemed unquiet, fidgeting and flapping blackly up there in the arms of that hollow gallows-tree.”

The Death of Bunny Munro was composed in a more straightforward manner, tracking the final days of a shoddy salesman as he travels around Brighton with his child. A petty lothario, Bunny cannot help but see his life fall apart before his—and his boy’s—eyes. Though it remains fairly obvious Nick Cave made an attempt to tone down the lyricism for this second publication (why on earth would anyone ever advise him to do that?), the novel still delights with occasional flowers, particularly in its fast-paced and increasingly overwrought final quarter:

“Out of the night the great hulk of the Wellborne estate looms up, like a leviathan, black and biblical, and Bunny parks the Punto by the now empty wooden bench—gone is the fat man in the floral dress, gone are the hooded youths. Bunny steps out, his suit drenched, his hair plastered to his head, but he does not care—he is the great seducer. He works the night.”

And what could be more Nick Cave than that? He is a raconteur who delights in emphasizing his stories’ most sordid elements, in mixing the incongruous with the depraved, in creating beauty out of darkness (otherwise known as doing a Baudelaire; see The Flowers of Evil). By now, the source of his charm should be obvious to all: the modern-day bard, bearer of post-punk epics, is a great seducer. He works the night.