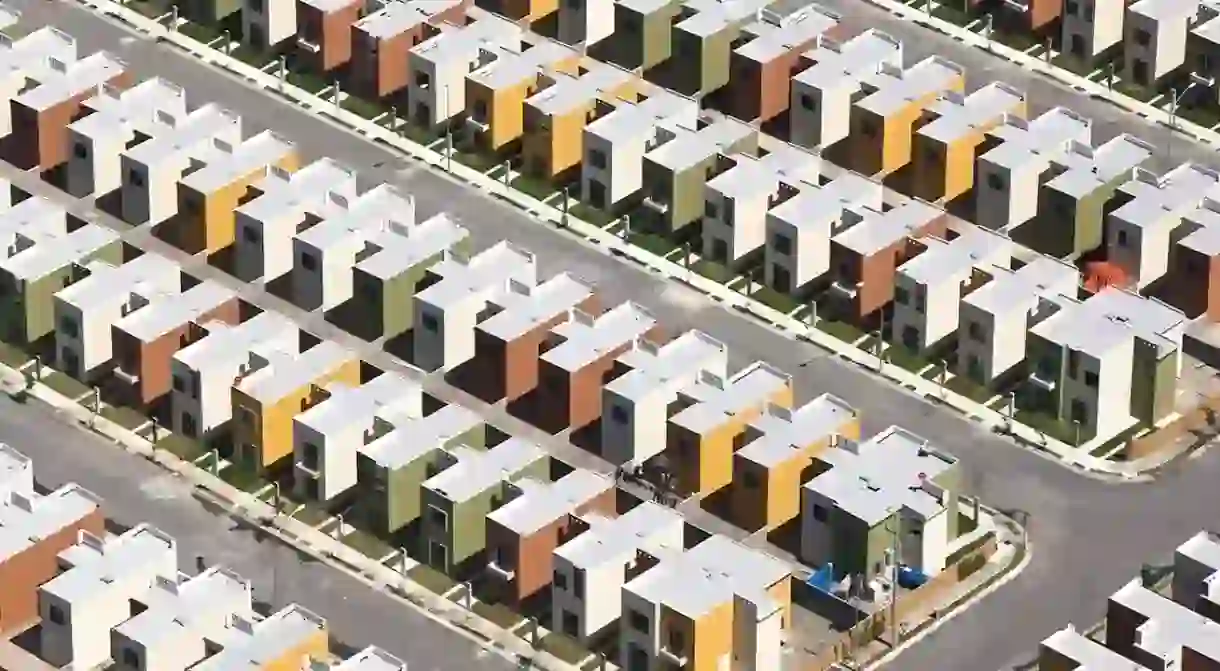

Welcome to Mexico's Eerie Identical Houses

There is something otherworldly and futuristic about the vast residential projects that you’ll find outside every major Mexican city. The identical, Lego-like concrete houses are bunched together in neat little rows and were once a source of great pride for the Mexican government. Yet today, many of the residents of these complexes live in cramped, squalid conditions and lack basic services, including sewage systems and running water.

In July, Mexican photographer Jorge Taboada is set to offer an exhibition showcasing amazing photographs of the many uniform housing complexes surrounding Mexican urban centers. Titled “Alta Densidad” (High Density), the series features aerial shots of the developments and will be featured at the Hamburg Triennial of Photography as part of group show called “[HOME].”

One of Mexico’s leading architectural photographers, Taboada was born in the northern city of Monterrey, a major industrial hub that took to the low-income housing model with particular enthusiasm.

A Disastrous Program

The complexes featured in Taboada’s work were built during the early 2000s when the government launched a massive initiative to provide affordable housing for millions of the country’s poor.

In November last year, a Los Angeles Times investigation highlighted how private investors – including major Wall Street firms and the World Bank – provided billions of dollars in funding for the housing scheme.

The new developments sprang up rapidly across the country, as the government sought to live up to Mexico’s Constitution, which stipulates that “dignified and decent” housing should be available for all citizens.

The scheme had a total cost of more than $100 billion, and some of this money was funnelled away by corrupt officials, developers and investors.

Many of the new housing units were mini-casas (mini-houses) built with cheap materials. These tiny homes were arranged in the sprawling projects showcased in Taboada’s photographs.

The mini-casa nightmare

During the low-income housing boom, developers sought to accommodate vast numbers of people in ever-smaller spaces. The Los Angeles Times investigation found that around 1 million of the new houses were a mere 325 square feet (30 square meters) – smaller than many garages.

Living conditions in such places can be horrendous. The thin walls of the structure mean that noises from adjacent houses are a constant fact of life, while limited space sometimes means that children sleep in hallways or cramp together in beds.

The government has now abandoned the disastrous housing scheme and many of the new developments are now deserted.

Still more have been left unfinished and without access to basic services. Families are sometimes without electricity for days at a time and even running water is scarce.

So despite the orderly shapes and organization of the housing projects from above, Taboada’s work ultimately tells a dystopian story.