The Forgotten Modernist | Architect Luis Barragán

Luis Barragán (1902-1988) was a Mexican architect, recognizable for blending the simplicity of his modernistic, color-blocked structures with the plants, terrain and natural light of his native country. In 1975, his work was featured in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and in 1980 he won the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize – but, despite this, he accrued little fame during much of his life.

Louis Barragán embodies the Modernist movement in architecture: creative, thoughtful, and simple. Barragán was born in Guadalajara, Mexico in 1902 and trained as an engineer in his home state from 1919 to 1923. Although his engineering degree never, strictly speaking, came to fruition, he put it to use in different ways: an engineer of the arts, steering Modernist architecture in Mexico in a new direction, and becoming one of the most influential architects of the 20th century.

After he completed his studies, his family funded an excursion to Europe in 1925, where he became enraptured with architecture, landscaping and urban planning. He returned to Mexico to begin his first series of architectural projects, residential buildings in downtown Guadalajara. Though they brought him some recognition for their solidity of design and artistry, the traditional style Barragán utilized pales in comparison with the modernistic pieces he went on to create.

He traveled again to Europe and New York in 1931 for a bout of first-hand education in the modernistic arena. Barragán met the French Ferdinand Bac, a garden designer, writer, and risqué caricature artist, and the exiled Mexican-muralist José Clemente Orozco, punished for his critical and bloody depictions of the brutal treatment of peasants and workers. Finally, Barragan was introduced to legendary Le Corbusier, an architect and urban planner devoted to the minimalist improvement of overcrowded and impoverished cities.

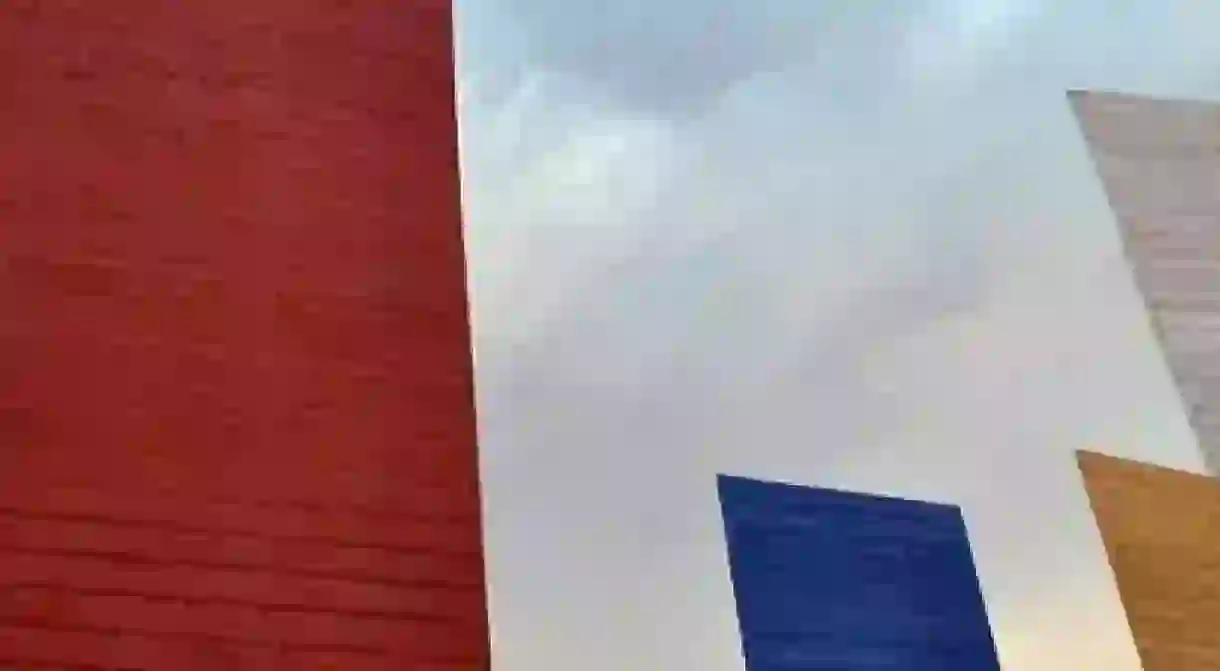

Barragán returned to Mexico, enlightened and intrigued by the idea of developing an innovative and personal style of Modernist architecture. Much of his renown came from his ability to mold his buildings into the Mexican landscape rather than awkwardly copying European models. He relocated to the post-volcanic landscape on the outskirts of Mexico City to begin work on his Jardines de Pedregal, in which he incorporated both landscaping and architecture by crafting elegant gardens that intertwined with and accentuated his trademark blocky and colorful housing structures.

The project was an economic failure at the time, yet – akin to the delayed success of Van Gogh – Barragán accrued renown for los Jardines well after their realization. He masterfully blended the starkness of modernistic simplicity with natural elements that utilized and accentuated the Mexican terrain and color scheme. The use of native plants and the manipulation of natural light were trademarks of his architecture, and set him apart as a genius in both Modernism and cultural appreciation.

Barragán’s architecture served a purpose beyond mere aesthetic pleasure. His 1955 rendition of the Convento de las Capuchinas Sacramentarias in Tlálpan was built to disseminate soft rays of natural light, mirroring the gentleness of convent life. His 1957 Torres de Satéllite, a series of urban sculptures (the tallest reaching over 600 feet), was purposefully designed to be viewed by vehicle. His intention was to not only symbolize a traffic-congested city, but also to energize daily commutes.

The concepts embodied in Barragán’s architecture helped define his legacy: his projects absorbed and beautified their surroundings, creating more than just a large number of structures. His individual virtuosity allowed him to convey usefulness and purpose within the simple minimalist lines of Modernism. The resolution of these two ideas, so starkly opposite, is what made him one of the greatest architects of the 20th century.