Prosperity for Some, Not Others, in the New China of "Crested Ibis"

A prizewinning Chinese film shows how economic and ecological upheavals have impacted a group of old acquaintances in a rural area of Shaanxi Province.

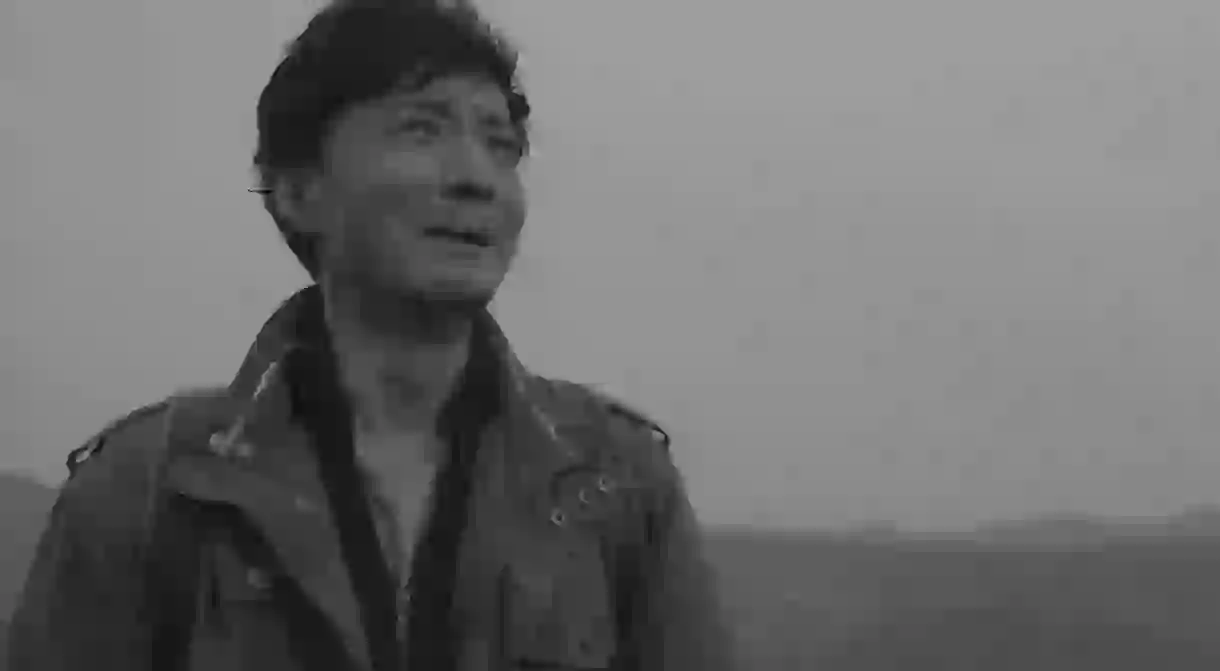

One of the undoubted strengths of Qiao Liang’s otherwise modest Crested Ibis is its sense of place. It’s set in the wide, empty landscapes of Shaanxi Province, which are as much a presence in the film as the characters whose drama plays out in their shadow.

The highland beauty of the Tongchuan locations must be impressive in reality, but Qiao has been uncompromising in shooting Ibis in black and white, creating a visual atmosphere that somehow sets it out of time. Though it took the main prize at June’s Moscow International Film Festival, it certainly isn’t arthouse fare, rather a story told along traditional, even conventional lines.

Shades of grey

That visual choice, the director has acknowledged, was also dictated by one of the film’s subjects, ecology. The grey hues in cinematographer Huang Lian’s palette—no sharp contrasts of black and white—reflect the presence of a huge cement factory that pollutes the district. But although such environmental concerns certainly feature, the film’s real preoccupation is the reappraisal of past relationships precipitated by the reunion of sometime school contemporaries.

Wen Kang (Gao Zifeng) is the local boy made good. His career as a journalist has taken him as far as Beijing; for the others, reaching even the provincial capital Xi’an seems something of a dream.

Not that Kang’s success has brought him happiness: an early scene makes clear that his wife is divorcing him, taking their child. It’s an element undeveloped except to emphasize that, when Kang is sent back to his home village on a work assignment, he is already somehow detached from the ties binding him to his new life.

Mixed blessing

He has obviously been home before for professional reasons. His first encounter when he gets off the bus in the local town is with a school acquaintance now working as a taxi-driver after losing his job at the factory after one of Kang’s previous reports revealed how much it was damaging the local ecology.

This time Kang has come back for a different story. The film’s opening sequence shows the finding of a rare crested ibis in the area (the bird has long been a protected species in China, and Shaanxi is the region where it is most often found).

If the finding is confirmed, it might result in the region being transformed into an environmentally protected zone, which would mean closure of the factory and loss of local employment.

Officially, the enormous facility may now be equipped with all the necessary pollution-minimizing devices, but we learn that, for economic reasons, they are only turned on when an official inspection is due.

Death of a mentor

The conflict between private loyalties and wider convictions is key to the film. Kang’s return has coincided with the death of his school teacher, who clearly did much to further the young man’s career.

The action unfolds against the backdrop of the ceremonies leading up to his burial, following traditional rituals and including performances of Chinese Opera, which creates a nice portrait of village life. All this is funded by the factory owner Wanpeng Ren (Zhao Jifeng), who has competition issues with Kang that date back to their schooldays.

Qing Shang (Meng Haiyan) had been close to Kang before his departure, so there’s frisson in their reunion. She now lives practically in poverty, her life changed irrevocably, we discover, by her past work at the factory. Her character is set against the effervescent Wen Tong (He Miao), who is now Ren’s media manager, as well as his mistress. It’s a familiar story: some have kept up with change, others have been left behind.

No eruptions

Crested Ibis is adapted from the eponymous novel by Zhang Ping, who is also Vice Governor of Shaanxi Province. If there’s a discrepancy in Li Yong’s screenplay, it’s that Ren continues to live so spartan a lifestyle in his home village; he has resisted relocating to somewhere more compatible with his status and presumed wealth.

There’s not a trace of the reality of China’s New Rich here. Quite the opposite: these characters might just as well be living in, say, the 1980s as today. The lack of definition seems slightly forced.

Qiao takes his narrative development slowly, holding back from an obvious denouement. The conflicts between characters simmer rather than erupt, and the film builds incrementally to a conclusion that resonates all the more powerfully for being understated. Crested Ibis may not be particularly original, but it has an intelligence,a conscious simplicity that stays with you longer than you might expect.