Dancing, Singing, and Dying in "Moscow Never Sleeps"

Irish director Johnny O’Reilly gives Moscow a glossy sheen in his comedy-drama about its stressed-out citizens, but there’s no concealing the stains beneath the veneer.

A pale, grey man is stretched out in what could be a morgue at the start of Moscow Never Sleeps.When his eyes open, he asks a nurse if he’s in heaven or hell. No such luck—he’s still alive in the Russian capital.

It’s impossible not to conclude that Valeriy (Yuriy Stoyanov), an alcoholic TV comedian with a terminal heart condition, embodies Vladimir Putin’s morally exhausted Russia—like the skeleton of the beached whale in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s searing Leviathan (2014).

The symbolism becomes even more obvious when Valeriy is kidnapped by a gang of young louts. He fights back a bit and even struggles with the idiot who pulls a gun on him, but that’s because he’s reached the point when it doesn’t matter to him if he lives or dies. The booze he’s craving will finish the job anyway.

Moscow Never Sleeps is a fleeting day-in-the-life look at members of two connected families and other Muscovites with whom they’re entangled. Spliced together from panoramic aerial shots and vignettes, it’s like an ironic version of Dziga Vertov’s Soviet documentary Man With a Movie Camera (1929) blended with Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia (1999) and given a sprinkling of Richard Curtis’ Love, Actually (2003).

One of those heavy-set, world-weary types women adore, Valeriy has a wife and a long-term mistress (Elena Babenko), who know about and tolerate each other. He also has an estranged son, Ilya (Oleg Dolin), who is stalking his ex-girlfriend, the pop singer Katya (Evgenia Brik). Katya returns his feelings but, as the trophy wife of the oligarch Anton, values material comforts and her career more.

Played pugnaciously by Leviathan’s Aleksey Serebryakov, Anton is emigrating to New York so he can fight from a safer distance the Russian government, which has hijacked a property development deal he’d put together. Anton’s ex-wife and small son are just blips on his radar.

Another strand follows two teenage step-sisters, Lera (Anastasia Shalonko) and Kcenia (Lubov Aksenova), who live in a cramped apartment with Lera’s mom Luba (Anna Gulyarenko) and Kcenia’s dad Vladimir (Mikhail Efremov). Just as party girl Kcenia bullies the introspective Lera, so would-be bon viveur Vladimir abuses the long-suffering Luba.

Early on, Vladimir dumps his near-mute mother Vera (Tamara Spiricheva), an elderly pianist who may not be as senile as he thinks, into a care home. She has been living with his first wife’s twenty-something son Stepan (Sergei Belov), whose partner Masha (Sofya Resnyanskaya) resents being the old lady’s primary caretaker. Stepan can’t bear the thought of her being left to die alone.

Though Moscow Never Sleeps isn’t confrontationally political, except in the brutish Anton’s manipulation by brutish apparatchiks, it self-evidently takes the point of view that the personal is political.

The compromising desire for upward mobility that dominates modern Russian city life has afflicted Katya and a reasonably well-off middle-aged couple with whom Lera thinks she has a vital connection. Kcenia has started to whore herself and become a drinker like her father and dead mother. Masha wants to make a fresh start without being burdened by Vera. The movie’s upbeat tone shouldn’t be mistaken for superficiality; selfishness, O’Reilly suggests, has become the sine qua non of Russian society.

Though family love and romantic love lie bleeding, Lera and Stepan are holdouts against this tendency. Young people discovering their integrity, both want answers about a lost parent: a ghost of the faintly more benevolent Russia they first knew (or imagined they did). They emerge as the film’s most sympathetic characters, representing a measure of hope for the post-Putin era.

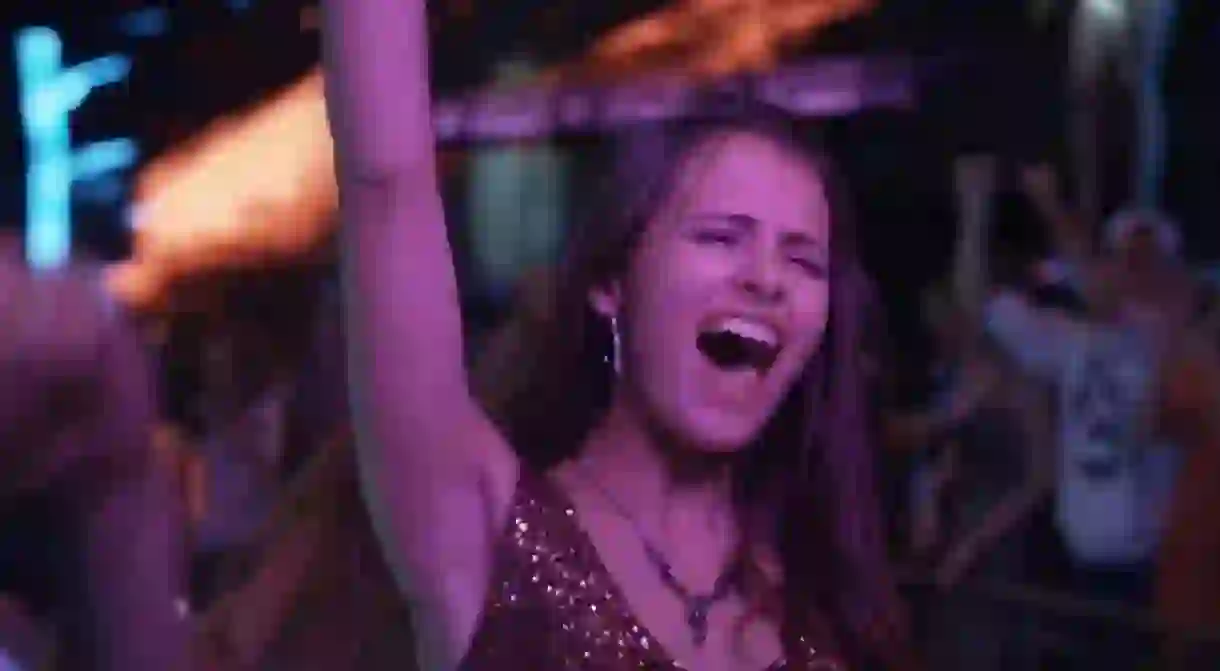

Counterpointing the erosion of human values, the film’s setting is a booming metropolis—class-divided, gridlocked during rush hour, a mecca of Eurotrashy clubs at night. Fedor Lyass’s cinematography is sharp, clean, and fluid. The tone may be mock-celebratory, but shots taken from a helicopter scudding directly overhead would suit a National Geographic documentary.

The story unfolds on Moscow City Day and culminates with a fireworks display. It’s both a magnificent send-off for the two characters who’ve died and propaganda for a cynical civic culture in which the lifeblood is vodka.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nyEkMN6lQKs