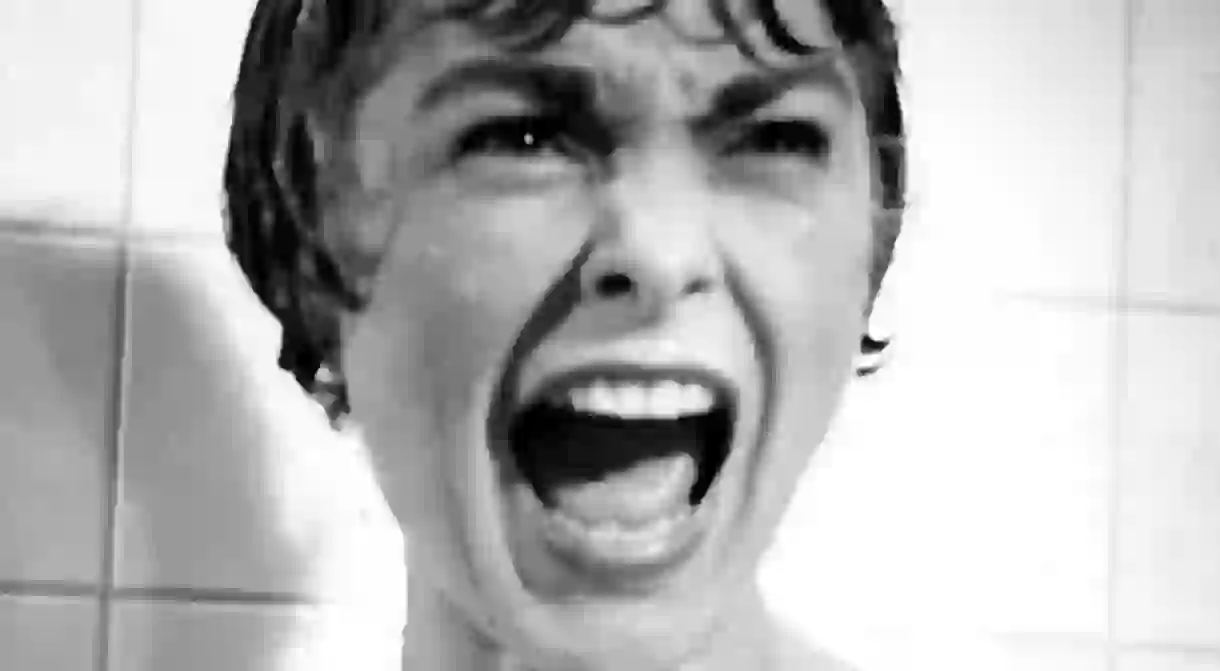

A Troubling Documentary About the 'Psycho' Shower Scene

Alexandre O. Philippe’s 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene parsesthe frenzied stabbing of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) by Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). This makes for an entertaining piece of film history—but a worrying piece of sociology.

To tell the story of how Hitchcock shot the celebrated shower scene and how George Tomasini edited it, Philippe relies on 39 interviewees to propel the narrative. 78/52—named for the scene’s 78 camera set-ups and 52 edits—moves along at quite a click.

Initially, it reconstructs Marion’s drive to the Bates Motel before the talking heads get down to contextualizing Psycho within Hitchcock’s oeuvre as an anomalous black and white B-movie amid his run of sumptuous, elegant color thrillers. The documentary’s centerpiece is an elaborate deconstruction of the horrific scene.

Having slept that day with her divorced boyfriend (John Gavin), Psycho’s protagonist Marion has stolen $40,000 and gone on the lam, fetching up at the Bates Motel. She resolves to return the money, but Hitchcock the Punitive won’t let her wash away her sin.

He has Norman, dressed as his dead mother, stab Marion repeatedly to the sound of Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking strings score. Philippe starts the deconstruction of the chilling scene 40 minutes in, around the same time Hitchcock depicted Marion’s three-minute slaying.

Shock value

Walter Murch, the supervising editor on The Conversation and editor of Apocalypse Now, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and The English Patient, provides Philippe with the most meticulous analysis of how Tomasini created the scene’s chilling effects.

Tomasini brilliantly mosaicked together cameraman John L. Russell’s elliptical closeups of Leigh’s face and Marli Renfro’s body as Marion’s flesh is punctured and she slides lifelessly down the shower stall wall.

The sequence used jump cuts to intensify its shock value. A shot of Norman’s kitchen knife pulling away from Marion’s midriff was reversed so it that it looks as if the knife is about to pierce her.

The scene ends with the fallen Marion looking at the camera, shower droplets like Man Ray tears on her cheeks, her blood—diluted chocolate syrup was used, Renfro confirms—swirling down the drain. We are reminded that Hitchcock had filmed tiny vortices before.

Crotch patch

Some of the talking heads draw attention to the tendrils of Marion’s hair that are splayed against the while tiles and the curl of her right hand in extreme closeup. These physical details emphasize the terrible vulnerability of a defenseless, naked woman viciously attacked out of the blue by a knife-wielding maniac.

Renfro warmly describes her experience working on the film as Leigh’s body double. The crotch patch that is all she wore in the shower kept falling off, and she volunteered to remove it all together, but Hitchcock—whether gentleman or prude—insisted she keep it. When Renfro went back to work as a Playboy model, she didn’t bother to tell anyone she’d worked with Hitchcock.

Renfro worked seven days on the film. That Leigh only worked 21 days indicates how much importance Hitchcock attached to the shower scene, after which Psycho is comparatively dull until it’s disclosed who Norman thinks he is when he is in a fugue state.

Early on, some of the interviewees—notably academic Marco Calavita—make too much of Psycho as a sociocultural phenomenon.

Squalid killings

It’s one thing to acknowledge Psycho’s role in opening the door to widespread sexualized killing in the cinema. It’s quite another to suggest it was a kind of cosmically significant stepping stone between the quadruple Clutter family murders in Holcomb, Kansas, in 1959—the subject of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood—and the Manson Murders in 1969.

The majority of homicides by psychopaths are not connected to the historical moment, but are only retrospectively fitted into it. Psycho‘s highly aestheticized shower scene bears little relation to the squalid killings (one perhaps accidental) of two women by Ed Gein, the psychopathic Wisconsin body-snatcher, arrested in 1957, whose maternal fixation mirrored that of Norman Bates in the Psycho source novel written by Robert Bloch.

There is no mention of Gein in 78/52, though his desire to “become” his mother (by wearing a suit of human skin) presaged the movie’s Norman wearing his dead mother’s clothes.

The film’s interviewees also include Hitchcock’s granddaughter Tere Carrubba, Leigh’s daughter Jamie Lee Curtis, and Anthony Perkins’s son Osgood. Other contributors include Bret Easton Ellis; Eli Roth; Amy E. Duddleston, editor of Gus Van Sant’s shot-by-shot Psycho remake; Hitchcock scholar Stephen Rebello; and the critic and filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich, who says that he felt as if he’d been raped after he first saw Psycho.

Morally wrong

Former hobbit Elijah Wood watches the film with two other guys and says nothing remotely of interest. The great critic David Thomson surely shared many valuable insights with Philippe but was only given a few seconds of screen time.

No one writing or talking about Psycho denies that the shower scene is virtuosic. But the only interviewee in the film who allows that there is also something morally wrong with it is the drily acerbic Richard Stanley, the South African director of Hardware.

It’s doubtful, of course, if morality should ever be invoked when discussing art. Horror films provide thrills and release, and the best of them offer critiques of social malaise.

Marion Crane’s butchering is bone-judderingly frightening—the quintessential look-away scene. I’m not convinced, though, that Psycho has that much to say about American society in 1960, or that it amounts to anything more than Hitchcock’s gloatingly cold desecration of a seductive blonde woman—a woman he portrays intimately in order to make the viewer care for her. It makes one suspect that had he been able to show Norman’s knife buried two or three inches into her body and rending it, he would have done.

A lurch into foulness

The scene is so repugnant it’s hard to understand why it’s glibly praised, as it unquestioningly is by so many in 78/52. It’s inspiring of many lurid, “sexy” giallos and the American wave of slasher films directed by lesser talents than Hitchcock in the 1970s led to the legitimization, even institutionalization, of a vile strain of misogynistic cinema.

As for Hitchcock, he went on, eventually, to the serial killer suspenser Frenzy (1972), a lurch into foulness that even Psycho didn’t anticipate. He remains the most pathological of the great directors, and one of the most irresponsible.

78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene is screening at the IFC Center in Manhattan.