Quiet Riot: The Political Art of Saudi Arabia

Though the kingdom of Saudi Arabia as it exists today was founded in 1932, it is only in recent years that a local contemporary art scene has truly begun to take root. Saudi Arabia is still known internationally for strict censorship, highlighted recently by the sentencing of Saudi blogger Raif Badawi to 10 years in jail and 1,000 lashes. It is a reputation that seems at odds with the growth of a contemporary art scene, as contemporary art is so often tied to contemporary events and the expression of opinions about those events. However, the country’s art scene has been growing and artists haven’t been shying away from contemporary issues. Saudi artists have been quietly addressing political topics, exploring just what sentiments can be expressed and how under one of the world’s strictest regimes.

Over the course of the past week, art enthusiasts from around the globe could be found at Manhattan’s piers 92 and 94, enjoying 2015’s edition of The Armory Show. The Armory Show is a leading international art fair, and each year a curated section of this fair explores the artistic climate of a certain geographic region. For 2015’s Focus edition, curator Omar Kholeif highlighted the Middle East, North Africa, and the Mediterranean, or MENAM region. Fittingly, one of the main collaborators for 2015’s Focus MENAM initiative was Edge of Arabia, a nonprofit social enterprise dedicated to promoting the art and culture of the Middle East, and most particularly, Saudi Arabia. Below are just some of the works produced by Saudi Arabian artists over the last several years, all of which have been shown publicly in the country. While the country is certainly strict, these artists are navigating ways in which they can address sensitive topics in ways that can be celebrated rather than shunned.

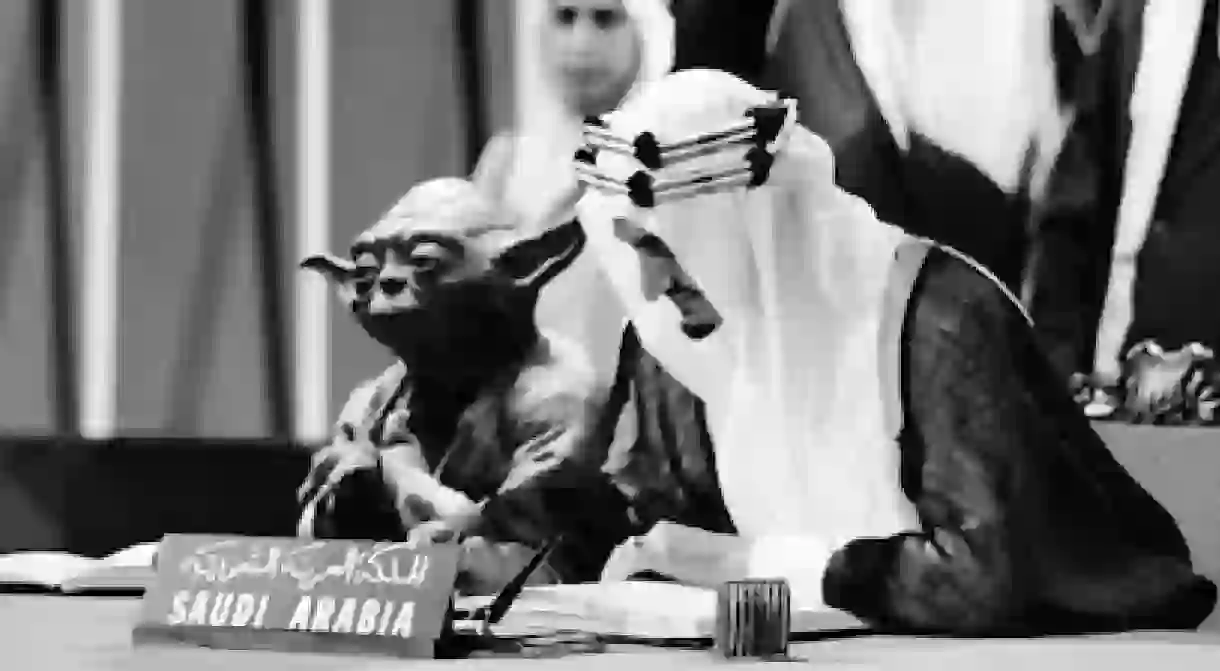

The Last Jedi Master, by Shaweesh

Though many may not associate the kingdom of Saudi Arabia with street art, artist Shaweesh proves a potent counter-example. His artistic career began when he felt the basketball courts near where he lived needed more color, and has since evolved into a broad, mixed-media practice. His body of work now includes several post-production pieces that play with viewers’ perceptions by depicting everything from Captain America interacting with Middle Eastern refugee children to familiar soldiers raising a testament to a fast food chain. Perhaps the most political of these works, however, is ‘The Last Jedi Master’ (2013), a piece that addresses the political structure of the country. At first glance, the image simply appears to be an old photograph documenting the late King Faisal’s participation in a meeting at the United Nations. It only takes a moment longer, however, to notice the small figure just over his shoulder, none other than Yoda, a character from the Star Wars franchise, appearing to act as advisor to the King. It’s a work that carefully toes the line of acceptability, as insulting the royal family would be a crime, but the image isn’t necessarily insulting. It’s a tongue-in-cheek mixing of popular culture and tradition, and can be argued and interpreted in many different ways, helping it avoid cases of overt censorship while allowing it to play with political themes.

Evolution of Man, by Ahmed Mater

In 2012, Edge of Arabia held an exhibition in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, titled ‘We Need to Talk’. Featured in the show was Ahmed Mater’s ‘Evolution of Man’ (2010), a work comprised of a light box depicting what looks like a series of x-rays, which address the role of oil in the country. When read left to right, the series depicts a gas pump transforming into a human figure holding a gun to its head. The work quite directly links oil with self-destruction, significant to any oil-dependent society. It’s a piece that would be read as political in most contexts and doubly so in a country like Saudi Arabia, where so much of the national wealth is derived from petroleum exports. It shows that Saudi artists are aware of these issues, and not afraid to engage with them. While it could be read as an indictment of the country’s relationship to oil, it could also be read as globally applicable, similarly accusatory to the nations relying on these explores, an reading that may have helped the piece pass the inspection of the government officials sanctioned to confirm the acceptability of works shown in ‘We Need to Talk’.

Brainwash, by Hala Ali

‘We Need to Talk’ also featured many works by young female Saudi artists, including an installation by Hala Ali entitled ‘Brainwash’ (2011). The title along lends itself easily to political connotations, and the work itself doesn’t back down from these as it addresses the country’s relationship to media. The piece is designed to resemble the large brushes of an automated car wash, but the brushes themselves are comprised of stacks of newspapers. Coupled with a title such as ‘Brainwash’, the piece speaks to the way media influences perception. The political nature of the work is only amplified when one remembers the strong hold the Saudi government has over media production within the kingdom. Similarly to ‘Evolution of Man’, the political nature of the work is couched in its broad application, as the work could as easily be about media around the world and is not necessarily specific to Ali’s own country.

Esmi – My Name, by Manal Al Dowayan

Manal Al Dowayan’s ‘Esmi – My Name’ (2012) is a work comprised of larger-than-life strings of prayer beads, each featuring a woman’s name and is a piece inspired by the status of women in Saudi Arabia. Islamic prayer beads are a common sight throughout the region and are obviously closely tied to religious belief, particularly for local audiences. There is nothing inherently controversial about this, of course, as the large prayer beads could easily be read as a celebration of the faith. A key part of the work, however, is the fact that each bead bears a woman’s name. When describing the project, the artist explained that she often observes disdainful attitudes towards female names in Saudi Arabia, something she felt had no basis in the Quran or Islamic teachings. The prayer beads became a way to reclaim female names and, in a sense, sanctify them. While the role of women in society is still highly contentious throughout Saudi Arabia, the artist’s work allows her to protest one unfair element, while backing of her work with religious doctrine offers the piece a certain level of defense.

21st Century Manuscript, by Ahmed Angawi

Lastly, Ahmed Angawi comments on Saudi Arabia’s rapid development and the ways globalization interacts with tradition and faith in his work, 21st Century Manuscript. At first glance the work, depicting the Ka’ba and surrounding area, would not look out of place in a much older manuscript, one that could be found in the Islamic art wing of any major museum. What makes this manuscript ’21st century’ in nature, however, is a small detail in the lower right hand corner, namely a small bulldozer plowing it’s way through the image’s border. Even in the religious centers of Mecca and Medina evidence of rapid development and globalization can be found, and the work suggests that this could be coming at the expense of the traditional values of these cities, or perhaps the country as a whole. However, the work avoids placing direct blame, and seems to side with protecting these holy sites, something that certainly helps avoid controversy. Instead, it invites all viewers to explore a topic many of them have likely encountered, but perhaps had not thought much about before. Of course, the works listed are only a small sample of artists and artwork being created, employing contemporary art as a means of communicating about contemporary issues. Other works circumvent biases against depictions of the human form by using x-rays, while another Saudi artist combines connotations of torture with the popularity and regional significance of falconry. There is no shortage of creative ways to approach sensitive topics. While Saudi Arabia may not be the easiest place to produce contemporary art, a growing number of artists are developing new ways to approach the paradox of contemporary art in Saudi Arabia and exploring just where the boundaries lay with a government that’s increasingly allowing these boundaries to be redrawn.

By Cassandra Flores