The Best Of London's Public Sculptures

London’s streets and parks are positively bursting with public artworks, bringing a touch of culture to even the most rational, financially driven districts. While there are many beautiful murals to be found on the side of the city’s buildings, it is the sculptural forms that often prove the most controversial, yet they are always intriguing. With pieces from traditional masters and some of the biggest names in modern art alike, here’s our round-up of London’s best public sculptures.

Nail by Gavin Turk, St Paul’s

This 40-foot-high bronze sculpture of a rusty nail was unveiled in 2011, the first permanent public sculpture by Gavin Turk — a prominent member of the Young British Artists — despite famously failing his postgraduate art degree after his final piece failed to impress his Royal Academy tutors. His installation, Ajar, can also be found in the garden of St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate, as part of this year’s Sculpture in the City programme.

http://instagram.com/p/BKGWhPfAy_B/

Winged Figure by Barbara Hepworth, John Lewis Oxford Street

This famous, Grade II-listed sculpture has perched astride John Lewis since 1963, and is perhaps Barbara Hepworth’s best known work — unsurprising, given its prominent position. Commissioned in order to liven up the plain stone wall on John Lewis’ brand new post-war building, Hepworth beat out several other artists with her design, which responded to a brief asking them to express ‘the idea of common ownership and common interests in a partnership of thousands of workers’.

http://instagram.com/p/BLimvN2jz4t/

Quantum Cloud by Anthony Gormley, North Greenwich

A colossal sculpture courtesy of Anthony Gormley — most famous as the man behind the Angel of the North — Quantum Cloud was commissioned in 1999 specially for the Millennium Dome site. Made using a computer algorithm to position 1.5-metre-long sections of steel around a central figure based on Gormley’s body, it’s the artist’s tallest sculpture, and at the time of its construction, was the tallest in the UK.

http://instagram.com/p/3_nlOfE1Hm/

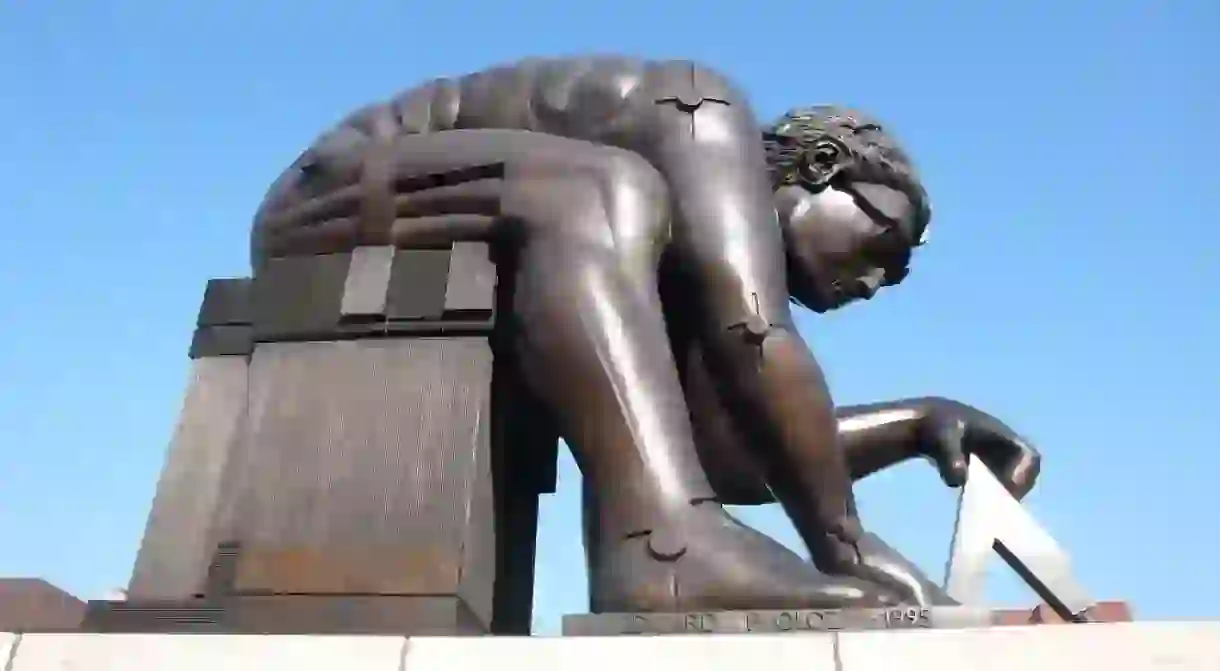

Newton After Blake by Eduardo Paolozzi, British Library

Based on William Blake’s 18th-century watercolour, pioneering Scottish artist Eduardo Paolozzi’s bust of Newton has sat in the piazza outside the British Library since 1995. Blake, a Romantic artist and poet, was famously opposed to what he believed to be the ‘single-vision’ of scientific rationalism and Enlightenment philosophy; his painting of Newton shows him crouched at the bottom of the sea, using a compass to draw on a scroll that projects from his own head. Paolozzi’s version depicts Newton as a mechanical being with his limbs bolted together, emphasising his impact on the way we view the world, as one governed by mathematics, playing on Blake’s antagonistic views. The seemingly opposing views of the pair — one an artistic genius and the other a scientific one — are combined into one form, representing the nature of the library.

http://instagram.com/p/BLlDhWRj2Ki/

The Burghers of Calais by Auguste Rodin, Westminster Palace

Celebrated French sculptor Auguste Rodin completed The Burghers of Calais, one of his most famous works, in 1889, with London’s cast having been installed in the Victoria Gardens outside the Houses of Parliament in 1914. The sculpture commemorates a moment during the One Hundred Years War, when Edward III of England demanded that six of Calais’s leaders surrender themselves, apparently for execution, in order to end the siege on the city and free its people from the brink of starvation. Depicting the six burghers as they walked to their death (although they were ultimately spared), Rodin’s magnificent sculpture was controversial, given its rendering of the group in humble, unheroic terms; Rodin maintained that he captured the anguish, pain, and ultimately, heroism of self-sacrifice. Though set on a plinth, his sculpture was originally intended to be at ground level, so that passing people could mix with the figures as though they were among them.

http://instagram.com/p/BCjKH3vQc5l/?taken-at=225322058

Fulcrum by Richard Serra, Broadgate Circle

Named as one of London’s design icons by Deyan Sudjic, director of the Design Museum, site-specific American artist Richard Serra’s monumental sculpture, Fulcrum, sits near the entrance to Liverpool Street. Made out of five sheets of steel that weather without decaying — which appear to simply lean against one another, unconnected — the 55-ft.-tall Fulcrum follows in the vein of much of the artist’s other work, with three entrances inviting the viewer to step inside and explore, engaging their perception in the artwork itself.

http://instagram.com/p/BLQyNKAAJuI/

Slice of Reality by Richard Wilson, North Greenwich

Another piece commissioned for the Millennium Dome, Richard Wilson’s Slice of Reality consists of a sliced off section of an 800-tonne sand dredger ship moored off of Greenwich Peninsula, leaving the ship’s accommodation sections, the bridge and the engine room exposed to the elements of air and river. Celebrating the merchant shipping history of the East End of London, the sculpture is also a melancholy reflection on the death and decay of the area’s former industries. Over time, the exposed sections have been sealed off with glass, leading to speculation that the artist himself may hole up inside it from time to time.

http://instagram.com/p/BJksw-wBFuB/

Three Perpetual Chords by Conrad Shawcross, Dulwich Park

Unveiled in Dulwich Park just last year, Conrad Shawcross’ three looping sculptures are deliberately austere, made out of cheap cast iron. The piece was commissioned following the theft of a bronze sculpture by Barbara Hepworth, which had stood in the park since 1970, and which was believed to have been targeted by metal thieves. Heavy and large in scale — which, it is hoped, will keep them thief-proof — the three sculptures rest lightly on the grass, ‘emphasising the juxtaposition between an industrial material and its arcadia environment’, and are intended to encourage playful interaction from the park visitors.

http://instagram.com/p/3UQwOLCqu5/

Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square

The site of a continuous series of temporary artworks since 2007 — although three consecutive pieces also occupied it from 1999 to 2001 — Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth is often a site of controversy, with commissions being one of the most talked about accolades in the UK’s contemporary art scene. The plinth is currently adorned with David Shrigley’s Really Good, a seven-metre-high bronze sculpture of a hand giving a thumbs up, with the disproportionately long thumb proving a strange, 21st-century rival to Nelson’s Column. It has been interpreted by some as a defiantly optimistic symbol of belief in the continuing buoyancy of Britain in a post-Brexit world, while others believe the depth of its black colour and the incongruously thin digit instead speak more to a parody of the very British ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ attitude.

http://instagram.com/p/BLlSq04gm6k/