'Armand V' by Dag Solstad, a Novel in Footnotes

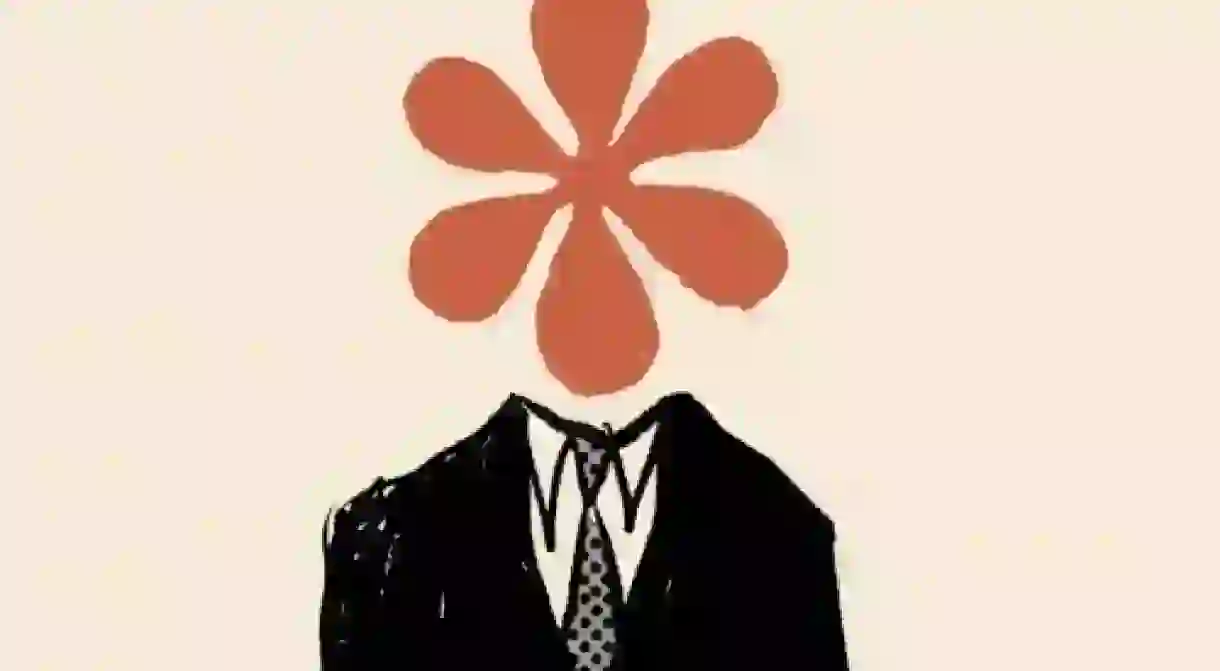

In Armand V, Norwegian writer Dag Solstad creates an entire work out of footnotes to a novel that doesn’t exist.

Armand V is not really a book at all. Comprised of 99 (one wonders why 100 was simply too many) footnotes to an imaginary text, Armand V recounts the story of a distinguished Norwegian diplomat whose ambassadorial duties take him from Oslo to Jordan, Budapest, Madrid and eventually London. Meanwhile, Armand’s son joins the Norwegian special forces, leading to a mild – none of Solstad’s characters could be described as volatile – crisis in ethics, as Armand questions how his service to his country’s foreign policy has led to the endangerment of his own son’s life.

Solstad is regarded as one of Norway’s finest writers by contemporary authors. A quick online survey will surface a cornucopia of lavish compliments about the Norwegian writer’s genius. Karl Ove Knausgaard – best known for his fiercely realist six-part novel My Struggle – wrote about how Solstad’s language ‘sparkles with its new old-fashioned elegance, and radiates a unique lustre’, while critic James Wood referred to the three of his works translated into English as ‘jewels’. Literary superstar Murakami is currently translating Solstad’s ‘strange novels’ into Japanese, while Norwegian novelist Per Petterson called him ‘without question, Norway’s bravest, most intelligent novelist’.

Despite his industry fan-club, Solstad is relatively unknown outside the publishing world and indeed Norway. With only three of his works translated into English – as Wood alludes to above – Solstad is mentioned comparatively rarely in relation to Norwegian literature to the likes of Knausgaard. However, three has now become five, as New Directions in the US and Penguin Random House in the UK release two more of Solstad’s works; T Singer which won the Norwegian Critics Prize for Literature in 1999, and Armand V, which won the Brage prize in 2006.

For a novel written in secondary, add-on material, the overall text (or non-text) hangs together in a curiously coherent way. Subtitled ‘Footnotes to an Unexcavated Novel’, Solstad’s unique creation invites the reader to piece together the fragments of narrative into a coherent whole – like archaeologists unearthing broken pieces of a mosaic. Certain passages – the rather tedious descriptions of his self-consciously intellectual social circle at university – are unnecessary, even for a footnote, which is impressive, seeing as footnotes are already considered unnecessary to the original text. But, this is what makes the work so satisfying – it is actually rather life-like. As the narrator ponders: ‘This lack of coherence is extremely troublesome, yet at the same time extremely accurate with regard to the way life is experienced.’

It wasn’t until the 1980s that Solstad began experimenting with metafiction – his work in the ‘60s and ‘70s was decisively political with a left-leaning energy – but it appears he has turned experimentation into a craft. The engine that drives Armand V is the book’s continual observance of its own non-existence. Where Solstad triumphs in turning formlessness into form, in turning a book that isn’t a book, into a book. In the beginning of the novel, the footnotes are peppered with whimsical references to ‘the text above’ maintaining the illusion that some original text exists, like dark matter, intangible but proven. But as the work continues, the purity of the illusion begins to fade, as the narrator (or Solstad) reveals: ‘wishing to write a novel about the Norwegian diplomat Armand V., I’ve decided the best way to realize this is not by writing a novel about him, but by allowing him instead to appear in an outpouring of footnotes to this novel. The sum of these footnotes, therefore, is the novel about Armand V.’ Formlessness has become form.

This subversive, rebellious, self-annihilating kind of writing is shared by Solstad’s fellow countryman, Karl Ove Knausgaard. Writing in the London Review of Books, author Ben Lerner discusses the attempted ‘literary suicide’ of Knausgaard that fuels the energy of My Struggle. In other words, by writing everything, he will end up with nothing. If Knausgaard destroys through overwhelming presence, Solstad annihilates through absence, but their literary projects share a similarly subversive ambition. (The twin to Solstad’s Armand V might be the section in László Krasznahorkai’s The World Goes On, where a chapter of consecutive blank pages is followed by several footnotes to the preceding, absent text.)

As a reader, there is something infuriating about Solstad’s work, as if we aren’t getting what was promised, but rather the frozen, reheated leftovers. But what the book does trigger are larger questions about storytelling, and the ways in which we shape the narratives of our lives – why do some things earn a place in the text while others are relegated to the irrelevant footnotes? What Solstad reminds us, is that all experiences – even the non-experiences – can be transformed into substance.

Armand V by Dag Solstad will be published by New Directions on May 29, 2018