Karl Ove Knausgaard Turns Inward in the First Volume of His New Series

Autumn offers quieter, more meditative considerations of the world than any volume in the author’s celebrated tell-all My Struggle.

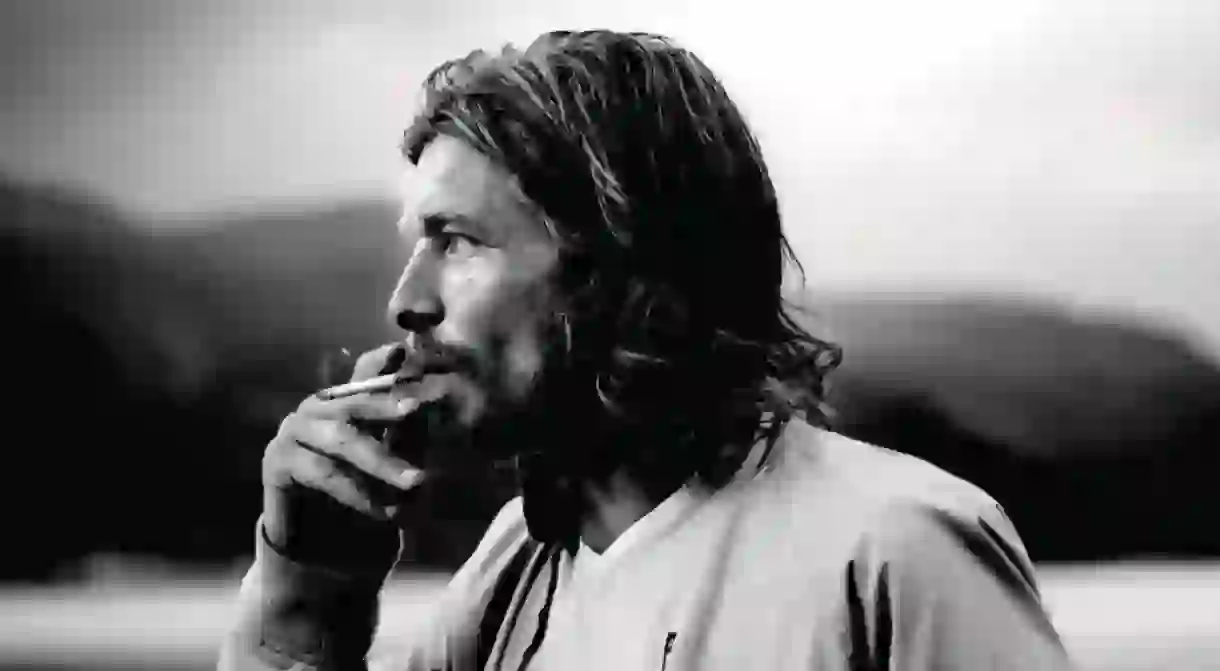

The Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard has, until now, chosen a somewhat difficult path for himself. If he seems a bit worn out, we should be understanding. Novelists, of course, do have a tendency to suffer unduly, in their work and in their life, and in this he is no exception. But if writers must agonize over every word, then surely he has endured more than most, for if you know him at all, you know him as the author of My Struggle, the autobiographical super-epic stretching across six volumes—enormous in size, infinite in detail, merciless in self-examination, the project has also served its author with brutal blowback from his family and friends. And though critical and financial success has been delivered to him, one doubts if he’s enjoyed much peace these last years (he’s also had several children in the same period of time).

It is along such a weary road, or perhaps at the end of it, that he joins us now, new book in hand. The book is remarkably thin in comparison to his other works. It bears the becalming title of Autumn. It is broken into three- or four-page sections, each serving to describe an object or sensation in an idiosyncratic, yet elemental, fashion. (“The mouth is one of the five orifices of the body,” he writes in a section titled “Mouth,” and doesn’t fail to add that it’s “located on the forward-facing side of the head.”) Interspersed throughout the book are a handful of illustrations by Vanessa Baird, and these are pleasingly naïve in their effect, at peace with their own rudimentary draftsmanship, as though set down by an angst-less Munch. The quality of the translation from the Norwegian by Ingvild Burkey, clean and unaffected, further lowers the blood pressure. You could read the book forward or backward, in part or in whole, with nothing to fear for loss of information, insight, security, or excitement.

In short, this is one of the most tranquilizing published works you are ever likely to encounter. As you daydream across pages of total blandness (“the bed gently accommodates one of our most basic needs: it is good to lie down in bed.”), you are increasingly relaxed, so that when Knausgaard arrives at one of his more saccharine observations (“Holding an infant close to one’s body is one of the great joys in life, perhaps the greatest”) you will scarcely be disrupted, so gently does the remark fall into its soft-focus environment.

That Knausgaard has arrived at this de-stressed zone of literary activity does seem a natural, and earned, sequel for the embattled author of My Struggle. But he doesn’t frame it that way. The scaffolding within which he’s working—and which has given him the opportunity to inform us, for example, of the nature of the bed, “with its four legs and its flat, soft surface”—is the project of describing the world, object by object, to his fourth child. “Letter to an Unborn Daughter” reads the introductory header, and he addresses her explicitly at times throughout the book: “Showing you the world, my little one, makes my life worth living.” The bald sentimentality may have some readers glancing away from the page in discomfort. But Knausgaard has always had a genius for intuiting the dark forces that make prose compelling—and indeed, without this address to his daughter, the rest of the book’s search for elemental description would lack principle, and slip into incoherence.

But most likely you won’t be reading Autumn in order to peek into Knausgaard’s private missive, a prayer really, to his daughter. Nor will you read it purely out of respect for the poor man’s need to write something simple and unobjectionable after the herculean typing of his past books. Our motivation in picking up Autumn—and then Winter, etc., as this is the first in a tetralogy—will be the same as with all his books: because Knausgaard is our supreme magus of the mundane.

The phrase “total blandness” was used above—and that, as a description of his style, can be evidenced on almost every page—but Knausgaard’s ability to suffer that quality, to shoulder the existential heft of so much trivia, to peer down into life’s instances of thin gruel with patience and match them with the most scrupulous note-taking, transforms the material into a distinct pleasure:

“Chewing gum was only transgressive when we were seven, eight years old, when chewing a small piece of gum with your mouth open was cool and having your mouth full gave you a certain status. I used to save mine, I remember. One wad of gum could last for several weeks back then. The taste was gone after a few hours, but not the texture. That is no longer the case. Since everything nowadays is sugar-free, the taste disappears after only a few minutes, and the consistency becomes loose and grainy, having lost its elastic quality entirely. With one exception: Juicy Fruit.”

Not even such a long passage, yet it feels chockablock with opportunities to talk about anything else, to close out the gum reflections, move on to a topic of relatable value, and do something with a writing life. But Knausgaard persists, and it’s with a strange ineluctability that he arrives at the funny little delight of “Juicy Fruit.”

There are delights throughout Autumn, but they remain little, and only rarely are they funny. They are instead, mostly, instances of the neurotic vantage that Knausgaard brings to domestic life. It might not be what the protagonist of My Struggle set out to do when embarking on his literary career, but in fact, that is where he has been heading all this time, toward his fated cud, lacking in nutrition and “unworthy in all its insignificance” as he himself describes chewing gum—but pleasant, harmless, and quite relaxing, too.

James Copeland is a writer and poet living in Massachusetts.

AUTUMN

by Karl Ove Knausgaard

translated by Ingvild Burkey

Penguin Press | 224 pp. | $27.00