The Berlin Wall Murals Tell a Story – Just Not the One You Think

The longest continuous stretch of the Berlin Wall, the East Side Gallery is at once a historical artefact and living artistic creation. Controversy surrounding its restoration has opened up debate about artists’ rights and the way we remember the Cold War.

Every year, millions come to experience the ‘historic’ Berlin Wall at the East Side Gallery. But the murals on this 1,316-metre stretch of wall are not the relics of resistance some visitors imagine them to be; instead, they constitute an evolving artistic reflection on German reunification.

Between February and September 1990, 118 artists from 21 countries created 106 artworks on a remnant of the Wall, and, in the process, the East Side Gallery, the world’s largest open-air gallery. Imbued with optimism and solemnity, these murals perfectly captured the zeitgeist: elation at the events of the previous November and heaviness connected with memorialising the division and hardships of the Cold War.

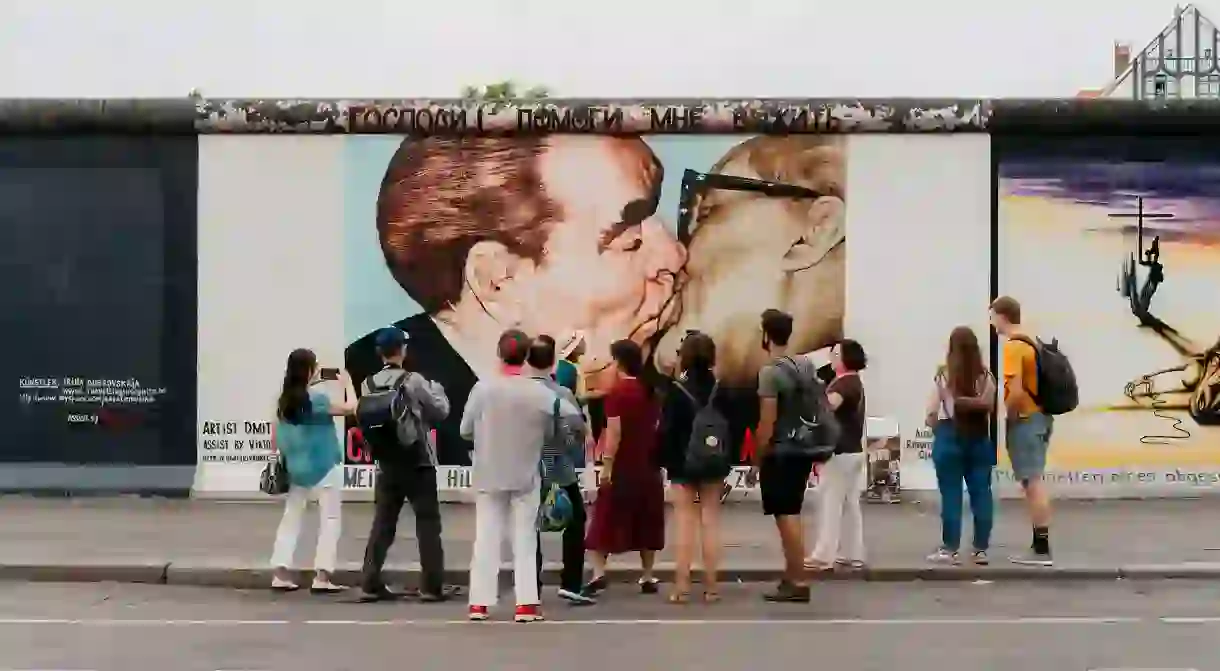

In this sense, they echo the era, while offering a preventive against historical amnesia. Among the most epochal images is Russian artist Dmitri Vrubel’s My God, Help Me To Survive This Deadly Love – also known as the Fraternal Kiss. It depicts the embrace between Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and East German head of state Erich Honecker at the 30th anniversary of the creation of the German Democratic Republic, in 1979. The image conveys the political kinship between the GDR and the Soviet Union, while the title, which appears on the mural, adds a satirical layer, given the ultimately calamitous nature of this intimacy. Equally evocative, Detour to the Japanese Sector by East German artist Thomas Klingenstein recalls a childhood wish to explore and live in Japan, experienced at a time when travel from the country was strictly controlled. Elsewhere, German-Iranian painter Kani Alavi’s Es geschah im November depicts, in haunting fashion, a horde pouring into West Berlin.

In November 1991, this portion of the Wall was designated a national monument and, five years later, Alavi founded the East Side Gallery e.V. artists’ initiative to oversee the preservation of the works; nevertheless, years of exposure to the elements and vandalism badly damaged them. In 2002, German art historian Gabriele Dolff-Bonekämper commented on the difficulty – the near futility – of attempting to conserve the murals. “If we want to keep the images, they’ll have to be repainted,” she wrote. “If we want the gallery to be a living artistic reflection of our own time, new ‘original’ paintings must be allowed, covering the old originals.”

Following some minor renovations, the artists were invited to repaint their designs in 2009. The restoration was controversial: 21 artists refused to repaint their murals, deeming the fee they were offered insultingly low. They went on to sue the city of Berlin when the murals were “forged” by an urban renewal firm, claiming their works had been copied without their consent.

It’s also open to debate whether the artists who did decide to return to the East Side Gallery were able to faithfully re-create their original artworks. After all, how could they channel that same heady mix of jubilation, shock and sobriety that characterised the mood in 1990?

However you choose to look at it, this latest chapter in the history of the gallery is part of what makes it so special: it’s at once connected to its origins and an evolving response to those events.

This story appears in Issue 4 of Culture Trip magazine: Art in the City.