Sebastian Faulks and the Mystique of Paris

Paris, war and memory is a familiar trio in the works of British novelist Sebastian Faulks. In Paris Echo – Faulks’s new novel – the writer presents the city as a squalid, enigmatic metropolis, departing from traditional literary depictions of the ‘city of love’.

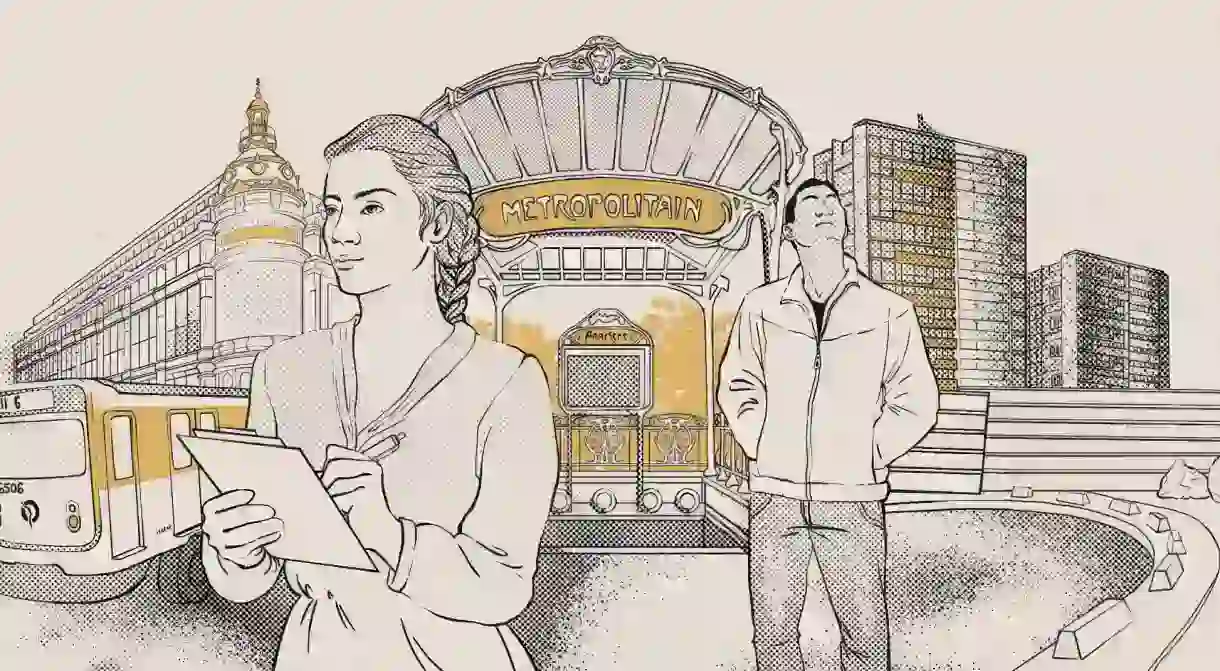

In Sebastian Faulks’s new novel, Paris is not the familiarly twee, charming city of Amelie or Midnight in Paris. Moonlit cobbled streets are replaced by the glaucous apartment blocks of Saint-Denis, while the soft sounds of late-night jazz bars give way to the city’s racketing metro. Daylight ghosts haunt its Haussmannian architecture as the shadow of its past looms menacingly over the present. It’s gritty, beguiling and infinitely mysterious.

For Faulks, what lies beneath the city is its greatest source of artistic inspiration. “I remember when at the age of seventeen – when I first went to live in Paris as a student for three months – being very struck by the names of the metro stations. They all had this great resonance, Censier – Daubenton, Barbès – Rochechouart, and it was mysterious and glamorous,” says Faulks.

In Paris Echo, the metro plays a dual role – a visceral reminder of the city’s rich history, and the novel’s structuring principle. Each chapter is paired with a metro name (“Gare du Nord”, “Belleville”, “Colonel Fabien” etc) that one of the characters passes through, anchoring the plot in the city’s urban underworld. Beyond acting as geographical and historical markers however, the metro – for Faulks – exudes something elemental about Paris: “I love the metro, I love the smell of it”, he says. “It’s the essence of Paris”.

Paris Echo traces the intersecting stories of Hannah and Tariq, who form an unlikely friendship while temporarily living in Paris in 2006. Hannah, an American history student, is there studying the lives of Parisian women under the German occupation. She spends her days at the historical archives in the upmarket 9th arrondissement, steeped in Second World War stories of resistance and revolt.

Tariq, a wide-eyed 19-year-old Moroccan, has come to Paris to explore the birthplace of his late mother and lands a job in a fast-food shop in the suburb of Saint-Denis. Their seemingly divergent lives converge as Tariq lodges in Hannah’s apartment. What she provides materially, he returns in kind, helping her with her French translations and providing momentary respite from the gravity of history.

The novel alternates between Tariq and Hannah’s perspective. Whereas Hannah is historically informed, Tariq is historically illiterate, a technique which pits his observations against the traditional flâneur narrative that is characteristic of Parisian texts. “I wanted him to record impressions of the city in a sort of I-am-a-camera kind of way, without cultural baggage.” It paints an original, dynamic portrait of the city, and one that avoids cliché.

If the underground is marked by stamps of history, Faulks’s Paris above ground is haunted by its ghosts. “One feels there is a lot that’s mysterious and quite concealed in Paris, inside these Haussmann boulevards and buildings,” says Faulks. “They seem – as Tariq reflects at one point – designed to keep secrets.”

This secrecy is embodied by Clémence, a character whose existence is questioned throughout the novel. “[She] drifts through the book,” says Faulks, representing a “mother figure to Tariq, or a possible revenant from the Second World War.” She reminds Tariq of “black and white films” and sings in a version of French he doesn’t understand. Like the facades of Paris’s fin de siècle buildings, Clémence is a shimmering apparition, who seduces and spurns in equal measure.

Faulks pins Paris’s ghostliness on its devastating exodus that occurred during the Second World War. “A lot of men were absent in German prisoner of war camps and a lot of people just fled the city,” says Faulks. “It had a sort of ghostly feeling during the occupation, so it’s not very difficult to imagine that again.” Faulks’s Paris is one that is stuck in time, ossified by the traumas of yesterday. It is therefore a fitting environment for Hannah and Tariq, who both embark on journeys to make sense of the past.

Since visiting when he was a Tariq-like seventeen-year-old student, Faulks believes Paris has witnessed another exodus of sorts. “The obvious change is that what you’d call a lower middle class French population, has largely, diminished,” he says. “The area around the first and second arrondissement, and the third, have become slightly museum-y.”

Faulks’s preoccupation with anamnesis pulses through his works. Charlotte Grey and Birdsong are both wartime novels, while his lesser known A Possible Life explores the past’s perennial interplay with the present. Paris has now emerged as the ideal arena in which to explore this theme with even greater impetus.

Paris has enchanted writers and poets for centuries, as Faulks’s epigraph to the book indicates. Quotes from Victor Hugo and Baudelaire sandwich Franz Kafka’s assertion, that “The Metro furnishes the best opportunity for the foreigner to imagine that he has understood the essence of Paris.” In believing the metro to be the city’s nucleus, has Faulks stepped into the very trap that Kafka warns of? Or does this say something more fundamental about Paris’s essence: that it is imagined rather than real, an alluring spectre that can never be grasped? In Paris Echo, Faulks masterfully reminds readers of the city’s indecipherable mystique and bottomless artistic generosity.