Lagos Soundscapes: An Interview With Sound Artist Emeka Ogboh

Armed with microphones, a digital recording device, and a video camera, Emeka Ogboh captures the maddening hyper-visuality of Lagos: vivid colours, the syncopated cries of street and highway hawkers, yelling bus conductors, the impatient bleats of car and bus horns, and hoards of people in constant motion. In collaboration with the Goethe Institut Lagos, Ogboh has launched an online live sound streaming of Lagos Soundscapes this year, coinciding with World Listening Day on July 18, 2013.

Lagos is the subject and object of your visual interest. What makes the city so attractive?

EO: I live and work in Lagos. I am deeply embedded in the city, just like everyone else living there. There is no way you can ignore the pervasive influence of Lagos. From the moment you wake up until you go to bed, you are affected by the city. As an artist, it’s normal that one’s place of domicile becomes the starting point of one’s work. Lagos is a very dynamic city and nothing is predictable. Things keep evolving at a fast and constant pace, which make for an interesting narrative. It is a city of many faces and parallels. It is the unpredictability of Lagos which informs my work.

An artist can approach Lagos as an erratic muse that needs to be disciplined and cuddled at the same time. It can also function as the artist’s ultimate Neverland. I am curious as to why sound became your main form of intervention, although I know you have since begun to work with video and photography as well, which we will get to in a moment. But let’s talk sound first.

If you have ever been to Lagos you will understand why sound is my preferred medium. One of the first impressions of the city is the intensity of its soundscapes. For a first-timer in Lagos, especially if you are from the Global North, it can be a shocking experience to have the city’s soundscapes invading your eardrums. But my forage into sound art actually began after I attended the media class on the audible spectrum taught by the Austrian multimedia artist Harald Scherz at the Winter Academy in Fayoum, Egypt in 2008. Upon returning to Lagos, I began experimenting with sound. I remember receiving a phone call from a friend around that time. This friend, who lives in Abuja, Nigeria’s political capital, was visiting Lagos. After 15 seconds into our conversation, I asked him if he was in Lagos because I could pick up the distinctive Lagos soundscapes in the background. He was startled that I knew that he was in Lagos. He had wanted to pay me a surprise visit. In a sense that phone call opened my ears to the uniqueness of the sounds of my city. So I started to listen, record, and experiment with these sounds. The more I recorded and listened, the more I appreciated their power to immerse and transport the listener. I find sound more engaging than any other medium.

At what point did the process move from the personal to become a work of translation for public consumption?

EO: I think it was from the moment I made a conscious decision to present Lagos Soundscapes to the public. Before then, I was mainly recording and listening in the quiet privacy of my studio, completely taken by my new discovery. As an artist, I thought about what I could do creatively with the sounds. When the opportunity came to show the project in a public context, the question of how to present it came up. How do you put together sounds that you have recorded around the city over a period of time into short clips for an installation? What sounds should be included or not included in a representation of Lagos? In short, what sounds would best sum up Lagos as a place? These were the questions I had to answer for myself.

So how was the initial public reception? If I am right, your first sound exhibition was at the African Artists’ Foundation in Lagos?

EO: No, it was at the Winter Academy in Fayoum, Egypt in 2008. I installed an audio-visual work in the academy’s bathroom. My first Lagos Soundscapes exhibition was at the AAF in 2009. I remember setting up the installation and not being sure what to expect from the public. But I think the idea of relocating familiar sounds to an unusual context gave the public an opportunity to listen to and appreciate Lagos differently. At the same time, many were just content with the idea of my work being a new thing in the art scene.

How have the sounds of Lagos changed since you first started?

EO: Lagos is largely a work in progress and throughout this period the city sounds of course have been in constant flux. New structures are being established, while old ones are being dismantled. This process has had a noticeable effect. Hawking, for example, has been banned on most of the newly renovated roads, but hawkers are a major part of Lagos Soundscapes. With plans for the government BRT buses to expand to all the bus routes, it is only a matter of time before danfo buses disappear completely. Imagine how Lagos will look without its iconic yellow buses. This means that the verbal mapping (the bus route calls of the conductors) will gradually disappear. Bus conductors are a very important element in Lagos Soundscapes. Their verbal mappings – by this I mean their solicitation of passengers – add authenticity to the Soundscapes.

This implies that your previous recordings are now historical documents or belong to an archive of memory. It will be interesting to see how the old recordings and what you do in the future will come together to present a more complex Lagos.

EO: True. When I first began to record, I did not envisage this development. I was only looking at things from a creative perspective and did not realize that I was slowly building an archive. It was only when Oshodi was restructured and renovated between 2009 and 2010 that it occurred to me that there had been a transformation in the sounds there. It was at this point that it became apparent to me that Lagos soundscapes were changing in relation to infrastructural developments going on in the city.

My goal is to create a narrative of the transformation of Lagos with the recordings I’ve already completed and those I have yet to make. I am not looking to work with only my own recordings but will seek out older recordings of Lagos from the past, such as archival video footage and other audio material.

To take our conversation in a different direction, I am particularly fascinated by how Lagos has become transportable or transposable in your work. You have been able to plant Lagos elsewhere and in several locations. In that way, you have made an interaction with Lagos ‘auratically’ phenomenological and imagined rather than physically experienced.

EO: My ability to create the interaction you just described lies chiefly in the medium I am working with. I have worked with other media in exploring Lagos (video and photography), but I have found sound to be the most powerful in conveying a sense of the place. Lagos soundscapes have a strong impact on the imagination. They cannot be ignored. I intervene by carefully choosing the sounds that completely embody or signify Lagos in a new environment.

Tell us about the audience reaction to your Soundscapes outside Nigeria.

EO: The reactions have been a mixed bag. They have ranged from positive to negative, as well as somewhere in between. Lagos Soundscapes have annoyed the hell out of some people, and at the same time stoked the curiosity of others. The work has been described as noisy and obtrusive, especially in some quiet European cities where it has been installed. In Cologne, someone broke one of the loudspeakers of the installation and the police were called in because the sounds were felt to be a nuisance. But for some people, Lagos Soundscapes was an intriguing intervention that added colour to the atmosphere.

I think the most interesting reactions to my work have come from Nigerians living abroad. The soundscapes stirred up their emotions and brought a whiff of home within earshot. One particular reaction was from a Nigerian student in Helsinki who thought he was having a mental breakdown when he came across the Lagos Soundscapes in a completely foreign environment. The experience inspired him to visit Nigeria that same year after being away for three years. In Cape Town, I remember some Nigerians heading out of their shops when they heard the danfo bus conductor screaming his lungs out on Adderley Street. So too, in Manchester, you could easily spot the Nigerians in the crowd based on their reactions to the installations.

Your most recent museum exhibition was The Progress of Love at the Menil Collection in Houston. You successfully installed a danfo bus. This was a shift from your more schematic representation of the danfo bus in previous exhibitions, with the yellow surface and two black stripes on the museum wall. What did the physicality of the actual bus add to the experiential context of your work?

EO: In my aesthetic universe, the danfo bus is a stable visual sign around which I assemble acoustic references to Lagos. It is further conceptualized as a spontaneous ‘agora,’ in transit, shifting Lagos or its people from one stop to another. As you rightly observed, the danfo bus has been represented in my previous works as yellow paint with two black stripes on a wall surface. That concept was strictly a visual one. It evolved from the painted walls to constructed and painted booths in other exhibitions, and finally to the corporeal presentation of the danfo bus in The Progress of Love exhibition. Having a danfo bus as part of my installation was transformational. It shifted viewers’ experience from the sonic to a more physical interaction with Lagos through its most iconic symbol. I think it created a more realistic experience of the city.

You have also begun to engage Lagos with other media, such as video and photography. Your Fractal Scapes are recent video experiments that treat Lagos in a radically different way than your work with sound. Can you talk a little bit about these new experiments and how they relate to your Soundscapes?

EO: My experimental videos are abstract ‘time-based’ paintings of Lagos. The city has been documented mainly through paintings, such as of market scenes, street scenes, skylines, bus parks, as well as of the inner city. Lagos has also been variously documented through photography. The paintings are either impressionistic or realistic interpretations. But they always present a singular view of Lagos, shorn of the city’s legendary complexity. They are static, and hang on walls in art galleries or in people’s homes. As an artist working with digital media, I love these paintings but cannot connect to their static quality. Nonetheless, they have provided a point of departure for me to use video to explore Lagos differently.

The Fractal Scapes are ‘mirror effect’ experimental videos. When exported frame to frame, the still images are reminiscent of the impressionist paintings of Lagos. I then introduce sound to create an audio-visual narration of the city. The video experiments are elemental but possess an abstract quality that I think points to the chaotic nature of Lagos. The Fractal Scapes address the complex nature of Lagos, a city that is navigable via multiple points of entry and departure. My video experiments are time-based paintings as opposed to the traditional two-dimensional paintings or photographs of Lagos. In an exhibition setting, the videos can be installed alongside Lagos Soundscapes to create a more immersive or embodied experience. I produce the videos with this idea in mind, although the videos and soundscapes can also be installed separately.

Lagos Soundscapes live sound streaming was launched on World Listening Day, July 18, 2013.

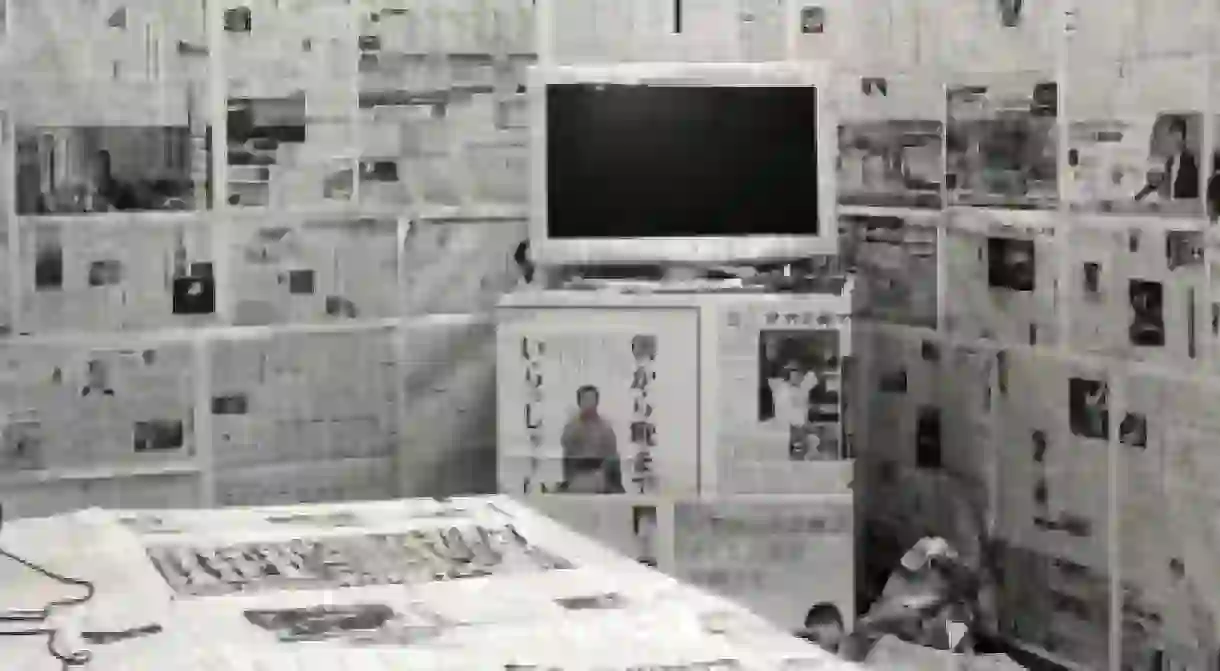

Emeka Ogboh lives and works in Lagos, Nigeria. He works primarily with sounds in exploring ways of understanding cities as cosmopolitan spaces with their unique characters. Emeka has exhibited variously in Nigeria, and internationally, at venues including the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos; Menil Collection, Houston; MassMOCA, Massachusetts;Shin Minatomura, Yokohama Japan; Museum of Contemporary Arts Kiasma, Helsinki, among others.

Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi (Nigeria, lives in USA) is an artist, curator, and art historian. He is a Smithsonian Institution Fellow and was recently appointed as the curator of African Art at the Hood Museum Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, USA. Nzewi was also recently appointed as one of the curators of the Dak’Art 2014.

By Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi

Originally Published in Contemporary And: A Platform For International Art from African Perspectives.