The 10 Peruvian Figurative Artists The World Needs To Know

Anything said about contemporary art in Peru will always have an opposing argument. But it’s a fact that the country’s art is pushing to break from a conventional scene and becoming more accesible to all crowds that seek a specific style in a bigger and more diverse pool of artists. The following list includes the 10 most interesting contemporary Peruvian figurative artists nobody should miss.

Salim Ortiz

Inspired by the work of Joel Peter Witkin, plastic artist Salim Ortiz’s paintings are charged with violence and lechery. Ortiz’s subjects are dead chickens, sinister dolls, fetuses and murdered victims (he’s “killed” many alive individuals like Nobel laureates, other famed painters and his own mother), all used to highlight the savage nature of his country. Ortiz, who likes to hang in places where morality doesn’t exist, has rebelled against the Peruvian art scene after a series of rejections from conventional galleries who tilted his work as grotesque, by holding his own art exhibits at brothels, gay bars or in the streets of a marginal barrios at hills, where, according to him, only his true followers will dare to go to see his work. Ortiz has achieved one of the purposes of art: his work provokes discussions and generates emotions, often getting the aberration and/or fascination of those who don’t fear to look at the aggressive and unvarnished side of the human condition.

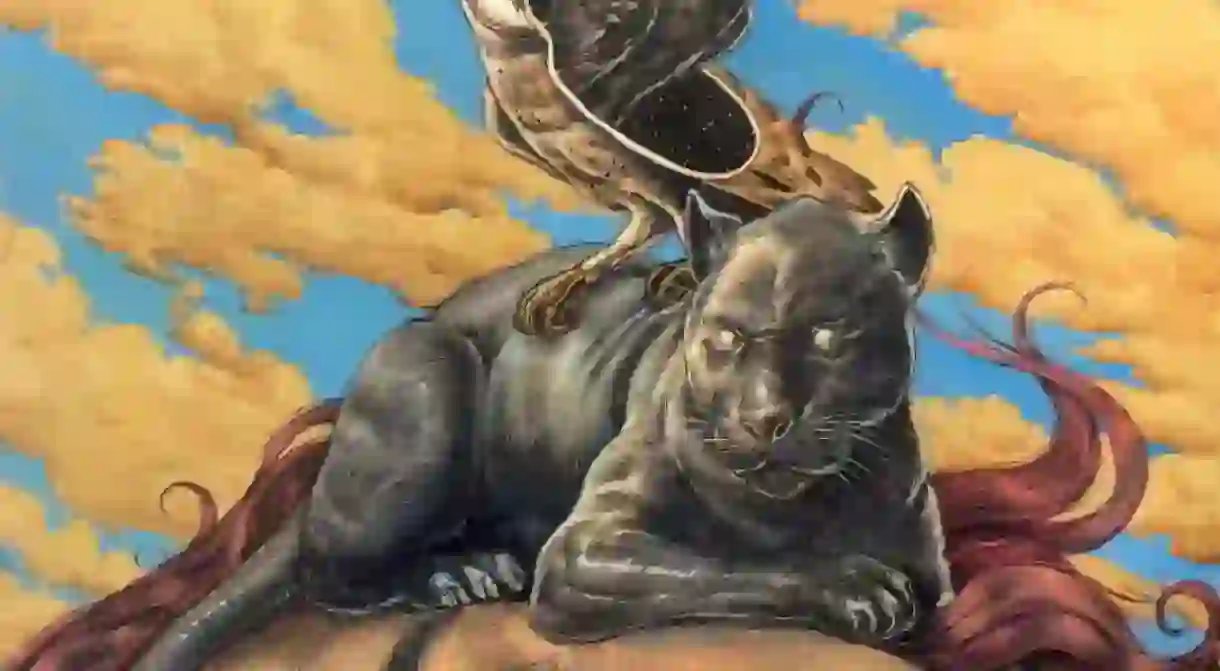

Jhoel Mamani

Jhoel Mamani sees the real world composed of fantastic elements. His surreal paintings come alive naturally; it seems like the characters are transitioning, shifting, from the inside out, perhaps looking to escape the frame and fly away. His work is plagued by birds —especially crows— anthropomorphic beings and hybrid creatures and female characters, depicted in watercolors, chinese ink and oil painting. Magical realism, he calls it.

Ale Wendorff

Ale Wendorff’s work is a see-through mirror to her life experiences, where the recurrent use of eyes and thin outlines withholds an enigmatic truth. The characters in her collages, drawings and paintings are in intense interaction with one another, in search for the root of their emotional processes within their own anatomy and voice. Her murals can also be seen all over Lima, in districts like Miraflores.

Jhoco

Jhoco’s latest work lies in expressionism at the verge of fauvism, prioritizing figures, traces and color. His characters appear in dark, sometimes sordid environments, seemingly pensive as they go through a long and unknown wait; they are variations of his personality marked by an existentialist behavior, with a psychological profundity.

Hugo Salazar Chuquimango

Hugo Salazar Chuquimango is a surrealist painter whose art is conceived during his night shifts as a guard, a time when silence and solitude complements the internal conflicts he must deal with in between dreams and paint after work. As an artist, Chuquimango has found themes in his past jobs, often painting self-portraits where he appears multiple times dressed as a guard and playing poker with himself, or as a crew member of a ship, surrounded by sirens or other terrible monsters.

Gala Albitres

A magnifying glass will come in handy when looking at Gala Albitres’ engravings and illustrations; every trace is meticulously done with the precision of someone who has a love and patience for her art work. Albitres’ art, which also includes drypoint and screen printing pieces, can have a linear narrative attached to them where the femininity of her characters reveal internal strength found in freedom. Albitres believes this is an act of resistance that rejects stereotypes and proves that women can be tender and subtle without being weak or submissive.

Amadeo Gonzales

Cartoonish, playful and curvy are the characters in graphic artist Amadeo Gonzales’ universe. Gonzales turns what could be a fun doodle into powerful art for a concert flyer or the front cover for a magazine, using an explosive combination of vibrant colors. His work doesn’t need much interpretation, it’s rather straight-forward, punchy. Gonzales and his brother Renso are behind “Carboncito” a comics and graphic arts magazine that features South American and Spanish artists. In 2015, he published a brilliant book titled “Bandas Inexistentes records”, a set of illustrations of imaginary bands.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Waw6n8qdUM

Fernando Gutiérrez Huanchaco

Fernando Gutiérrez Huanchaco uses photography, sculpture, video and painting to explore cultural dynamics within a city. His work “La chucha perdida de los Incas” (translated to “The forgotten pussy of the Incas”) is based on deceased artist and anti-hero Mario Poggi’s search for a sacred object linked to fertility and the origins of the Incas he is said to have found in the Amazon. In “La chucha perdida de los Incas”, Huanchaco does a remake of Poggi’s quest and presents the videos, maps, photographs and other tools he used during a real jungle expedition he went on shortly before Poggi passed.

Andrea Barreda

Women are present in her art as much as they’re in society. In an honest act of catharsis, Andrea Barreda paints realist outdoorsy scenes plagued with mystery and surrealist elements, some of which evoke the imminent arrival of death. The connection of her female subjects with the cryptic animals surrounding them, is strong and often perturbing. Like in her paintings and drawings, dreams can be landscapes full of exotic vegetation where we are left to face a concealed part of ourselves, a quiet wilderness we don’t know we carry inside.

Juan Javier Salazar

Every July 28, Peru’s Independence day, artist Juan Javier Salazar would get on a bus and sell stuffed maps of Peru to passengers. It was his way to give back the country to Peruvians in a form they could touch, feel or kick as they pleased. Salazar’s intervention, along with his other plastic and graphic arts work, was also his attempt to understand a country he thought to have been flattened out by a system ruled by elites he was adamantly against. His work was an irreverent and sharp —yet ironic and hilarious— space where he would argue in favor of decolonizing Peruvian history while criticizing the criminal establishment guilty of creating a contradictory narrative in a nation that “could’ve been” but never was. A truly remarkable storyteller, Salazar passed away in 2016.