Chilean Artists Remember Victims of Dictatorship Through Virtual Portraits

Altogether, 1,198 people went missing during Augusto Pinochet’s brutal military dictatorship of Chile from 1973 till 1990. This visual project uses art and technology to create a powerful monument to their memory.

During Pinochet’s 27-year regime, an estimated 40,018 people were victims of torture and/or murder, including more than 1,000 people whose whereabouts are still unknown, referred to as desaparecidos (‘the disappeared’).

The numbers are hard to verify, as during and after the dictatorship Pinochet continually denied and covered up any cases of human-rights abuse during his rule. Only within the past decade have justice officials in the country processed cases from victims’ families to reveal that there were many people whose whereabouts remain unaccounted for and were presumed killed during the dictatorship.

Pinochet seized power on 11 September 1973, violently staging a coup that allegedly killed Chile’s president (and founding member of the Socialist Party) Salvador Allende. Upon assuming his role as leader of the country, Pinochet immediately set on eradicating any Socialist sympathies in the country, causing the murder, torture and exile of many (including UN Human Rights Commissioner and former Chilean President Michelle Bachelet). Presently, 11 September is the day that commemorates the victims of Chile’s dark recent past.

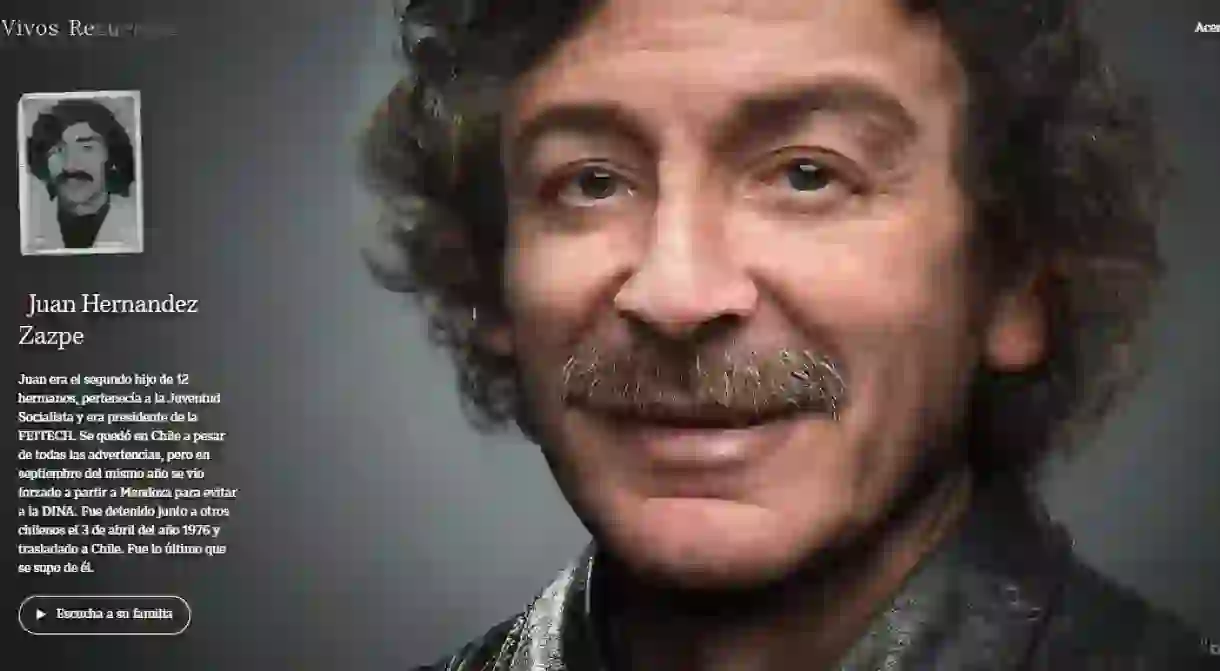

As part of a powerful campaign to remember the disappeared, the Socialist Party of Chile joined forces with creative agency Wolf BCP on an artistic project that remembers the disappeared. It’s centred around 10 people who were all young members of the Chilean Socialist Party at the time they were last seen.

Guided by pictures of the subjects taken before their disappearance, which date from around the early 1970s, the agency mixed technology and graphic art to create a depiction of each person as if they had aged and were still alive today. They also worked closely with the families of the disappeared to make sure every detail was as truthful as possible.

“It was a long process to compile the data and to talk to the family about how they would imagine them if they were alive today, to get any traces of them that could help the process,” said Sebastián Castillo, creative copywriter at Wolf, to a local news station. “We also looked at photographs of uncles, dads, people who looked like them, and could age in a similar way.”

One of the subjects portrayed was 25-year-old Sara de Lourdes, who was taken by National Intelligence (DINA) at 8am in the morning on 15 July 1975 outside the National Health Clinic in southern Santiago. Lourdes was arriving at the building for an internship, which was a part of her nursing studies. After she was taken for questioning, she was never seen again.

The portraits are free to view at the Socialist Party’s headquarters in central Santiago. There is also a video showing families’ reactions as they first see pictures of their loved ones. It was widely shared on social media alongside a website that provides more information about the project and each of the subjects.

As the website says, “The only way of not letting history repeat itself is by keeping the memory alive.”