The Photographer Recreating 120-Year-Old Images of Patagonia

Photographer Laura Ferro grew up on the Península Valdés, in Argentina, and has dedicated her life to documenting the history of this coastal part of Patagonia. In her latest project, she recreates 120-year-old images of the remote region, depicting the changing appearance of the landscape over time. Culture Trip reports.

On the long gravel roads of the Península Valdés, you can look through your rearview mirror and see cars coming up behind you from many miles away: they look like mini-tornadoes kicking up dust as they race through the empty Patagonian steppe. Península Valdés is characterized by an almost unfathomable emptiness, different from the Patagonia of the Andes, to the west, where mountains harboring ice-blue glacial lakes and dark-green pine forests loom over you like a postcard. The Patagonia of Península Valdés is more desolate: flat, barren, with foot-high shrubs and endless visibility.

There are no planes flying over, indeed there are hardly any buildings here, so at night the yellow-green landscape plunges into pure darkness and silence. On the coast, where sheer cliffs meet crystalline bays and coves (and, of course, the open sea), wildlife abounds: elephant seals, Magellanic penguins, sea lions and if you’re lucky, southern right whales and orcas. To the average visitor, it looks like a world largely unchanged from one or two hundred years ago; to those more intimately familiar with the region, however, even minor changes in the landscape reveal clues about the passage of time.

Laura Ferro, a 34-year-old photographer, is one of these people who can read the landscape. Her ancestors have been herding sheep on the peninsula since her great-grandfather immigrated here from Italy in 1888. Since she was a young girl, she’s heard stories of lonely gauchos out on the steppe, fallen asleep to the eerie songs of distant whales and documented the history of the people and nature of Argentina’s great Patagonian peninsula.

“This is a place where the past lives on all around you,” she says. “In fossils that are 30 million years old, in megalodon teeth, in old tools, in sharpened stones. In the landscape itself.”

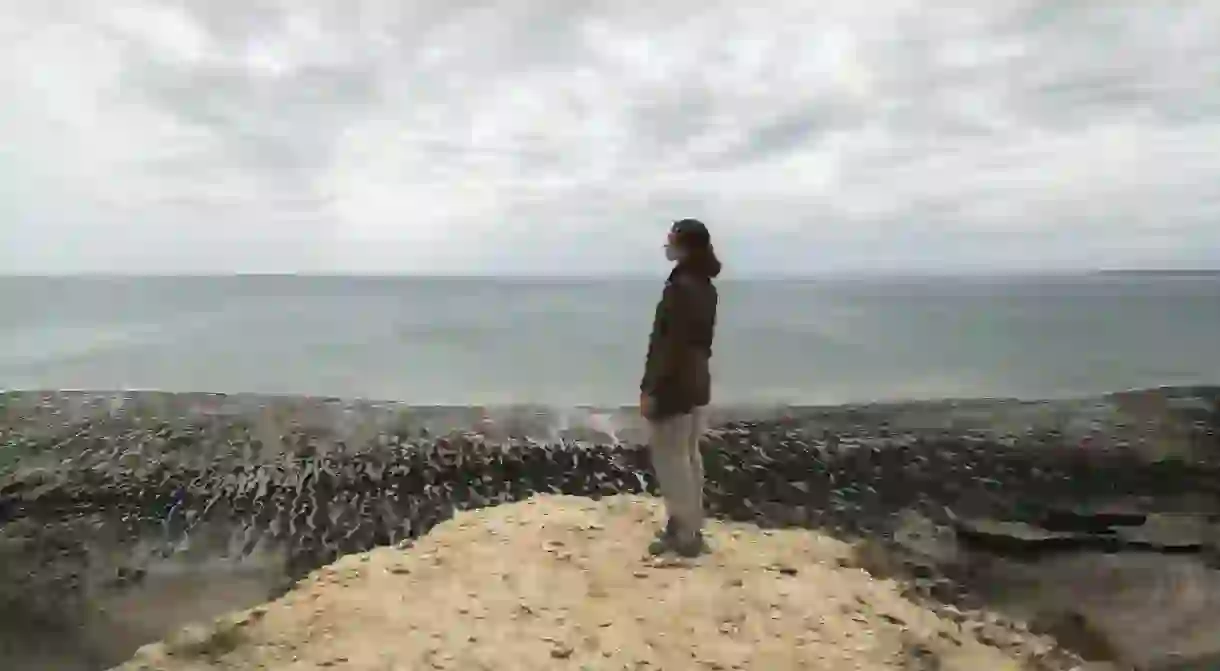

Ferro has always been fascinated by the concept of time and the different ways it can be made visible – that’s why she became a photographer in the first place. Now, in a new collection of photos called El tiempo es un paisaje (Time Is a Landscape), she’s recreated images that were taken 120 years ago to show what has changed – and what hasn’t. Carrying with her a camera and a trove of black-and-white photographs taken by an unknown visitor to the region at the turn of the 20th century, Ferro has roamed the peninsula and attempted to reconstruct the photos – taking them from the same position, and even going as far as to seek out the same wind and weather conditions. The many similarities that remain leave the few differences exposed. In one of the photos, the natural stone pyramid that once served as the namesake of the only town on Península Valdés – Puerto Pirámides – has crumbled and disappeared. In others, coastal erosion is clear. Despite the changes in the physical landscape, Ferro’s photos are remarkable reconstructions.

“I’m always reconstructing, always reconstructing,” she says with a chuckle.

Patagonia, in all its emptiness, has long attracted writers, artists and thinkers hoping to find meaning in its barren lands. Bruce Chatwin, inspired by a prehistoric bone on his grandmother’s mantel, set off through the south of Argentina in search of people who, for various reasons, were also drawn to Patagonia and decided to settle there; the result was In Patagonia, one of the most famous travelogues ever written. Descriptions in Antoine Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince are said to have been based on a trip the author took to Península Valdés.

Ferro is drawn to the region because of an innate, deeply personal connection that is inextricably tied to her upbringing. Her first book, Lo salvaje apareció en mis sueños (The Wilderness Appeared in My Dreams) is an ode to that childhood, and the family history that shaped it, in the form of photos and poetry.

In the book, she writes, “As if I were opening an old piece of furniture, I began collecting fossils, classifying maps, arranging photos, drawings, letters, and travel diaries.” And, she continues: “As the archaeologist of our family archives, I was reconstructing my own story.”

It helps that her grandfather, Emilio Ferro, kept an impressive library. His study, in the main house of the estancia that is still in the family today, was lined with dark-wood cabinets filled with original leather-bound volumes of geological and botanical surveys of the region, huge framed maps from centuries past and old photos of her great-grandfather and his fellow gauchos camping out in the fields. In a nearby wooden shed on the property of the main estancia, a creaky door opens onto dressers stuffed with more old papers, journals and ledgers than anyone but Laura knew what to do with.

One of the few mysteries Ferro hasn’t been able to solve, somewhat ironically, is the identity of the anonymous photographer whose work she has spent so much time trying to recreate. She’s narrowed it down to a few possibilities, but she will likely never be completely sure of their name.

What she does say with certainty, after following in their footsteps, is this: “Now I can understand his spirit. Always elevated, looking for the highest point from which he could document the natural world below. After so much climbing, walking, traversing winds and tides, finding the place where the body decides to stop and freeze that moment forever is a feeling like none other.”