AV&C + Houzé Explore the Boundaries Between Projection and the Physical in 'Phases'

This article serves as one piece of a four-part video series focused on the 2016 Day For Night festival hosted in an abandoned post office on the edge of downtown Houston, Texas in mid-December. A previously unseen combination of headlining musicians with gigantic, immersive art installations by world-renowned visual artists, Culture Trip investigates how Day For Night is establishing the festival of the future, and the works of those involved.

For AV&C’s Stephen Baker, David Bianciardi, and former team member Vincent Houzé participating in Day For Night has presented a rejuvenating break from commercial work schedules to create something that solely serves their own interests.

New York-based experiential design and technology studio AV&C work with artists, brands, and architects to craft digital landmarks in the physical world. Houzé uses modern computer graphics techniques to create interactive art, performances, and large-scale multimedia installations.

For the festival’s inaugural year, the trio constructed lull, an immersive installation that explored “the liminal state between conscious and unconscious.”

“We were interested in exploring the state where you fall into anesthesia and you experience dreams and hallucinations,” Houzé said. “We played with digital components which was like a light simulation that would interact with the billowing fog that was in the space, exploring boundaries between what was projected and what was physical.”

For 2016’s iteration of DFN, their new installation, Phases, rumor was that it was a reverse of their first installation, and the three of them had heard that, too, although it brought a brief chuckle. As Bianciardi explained, Phases is an exploration of a lot of the same components as lull.

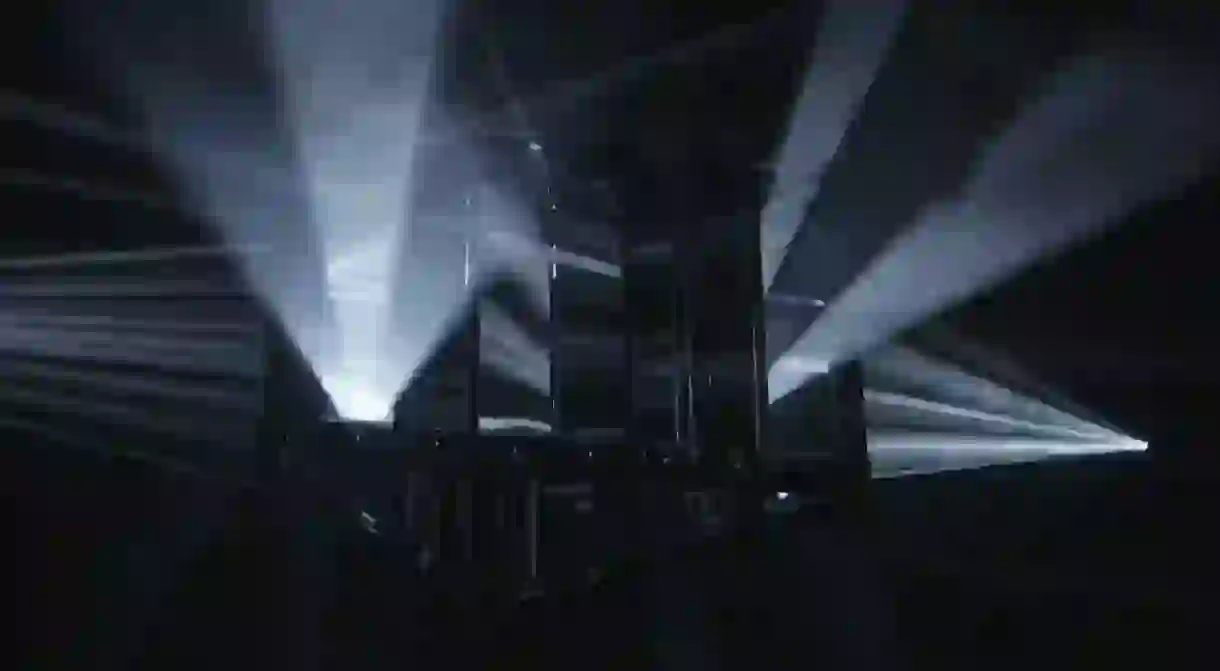

“We’re still trying to dimensionalize light and make it feel tangible,” Bianciardi said. “We’re creating this kind of dynamic sculpture of light, and it has this presence in the space. It has all these different levels still in terms of that central mirror assembly, what’s happening in the air, the scrim surface, and how it plays into the room beyond, but it’s the same materials: it’s projected light, it’s haze, and a surface that captures it in an interesting way. And there’s the sound environment, which Stephen is responsible for, the visuals and the sounds are all creating an environment.”

However, there’s still a lot that is different about Phases. Whereas lull was more organic, Phases feels more like a machine, and, while it might seem a bit antithetical, its personality is very, very strong.

“This year, to be explicitly different, we decided to be very graphic, very hard edges, very geometric, and that, in part, was informed by that we wanted to make a kinetic piece, a moving sculpture,” Baker said. “We have these mirrors that rotate throughout the space, and one piece that we found from the mirrors was that we had to be very graphic. The apparatus that we were projecting onto worked best with very strong shapes, so that gave us a very different feel even though we were using some of the same ingredients.”

“You see it in the way people respond to this space,” Bianciardi said. “There’s all the things that we want: people engage from far away down the hallway, they come around, they have these different relationships that go inside the piece, they sit down in a lot of cases. The whole range of interaction is there, but responses last year there was this blissful calm, emotional thing that happened, and this year it’s definitely ‘wow’ and all of that, but it’s definitely responding to [the installation’s] personality.”

Throughout the weekend, the pieces of Phases were moving in varying combinations and paces. At one moment, its projected shards would be spread across the scrim, gently buoying up and down in an ocean of light, almost at peace. But after a few seconds, the fragments would suck into one body and manically circle its cell, like some bizarre combination of a zord and the Smoke Monster from Lost, before exploding back into its many, glitching components and striking a brief pose. True to its name, there were many phases, some malicious and some more composed, but always unpredictable.

A huge part of the installation’s personality derives from its accompanying sounds. In line with its movements, Phases would rotate from a cold hum to snarls and crackles, like some sort of post-human form of communication. As Baker explained it, “musically this piece is very technical, very precise, there’s a lot of very low simple sine wave tones, very resonant types of sounds as well.”

Although Day For Night’s music lineup was largely recognizable for many of its attendees, the same level of awareness doesn’t apply to those behind the light installations. For whatever reason this divide exists — the art community bears some sort of barrier of inclusion, it has yet to figure out a way to inspire the same fan zeal as musicians, the rate of output and field of distribution are drastically different than in music, etc.— Bianciardi, Baker, and Houzé agree that Day For Night is helping to bridge this gap, drawing huge crowds that otherwise attend an event tied to their name and their peers. And it’s all being done on their terms.

“A lot of festivals are effectively, for all good and pragmatic reasons, are more commercialized,” Bianciardi said. “That tends to mean that if there are going to be expressions like this work that we do, we’re just as likely to be there at the behest of a brand than to do an art piece, whereas here we have the latitude to just like… there’s a focus on keeping the authenticity.

“It’s the right cross-pollination. It’s what’s happening in the culture. They’re on the edge of it.”

Watch the video above to view AV&C + Houzé’s installation and more of our interview with them.

Check out the other parts of this four-part video series on the 2016 Day For Night festival:

Day For Night Isn’t the Music Festival of the Future, It’s an Evolutionary Jump

How Magick Helped Damien Echols Survive Death Row

Michael Fullman’s ‘Bardo’ Probes the Physicality of Light