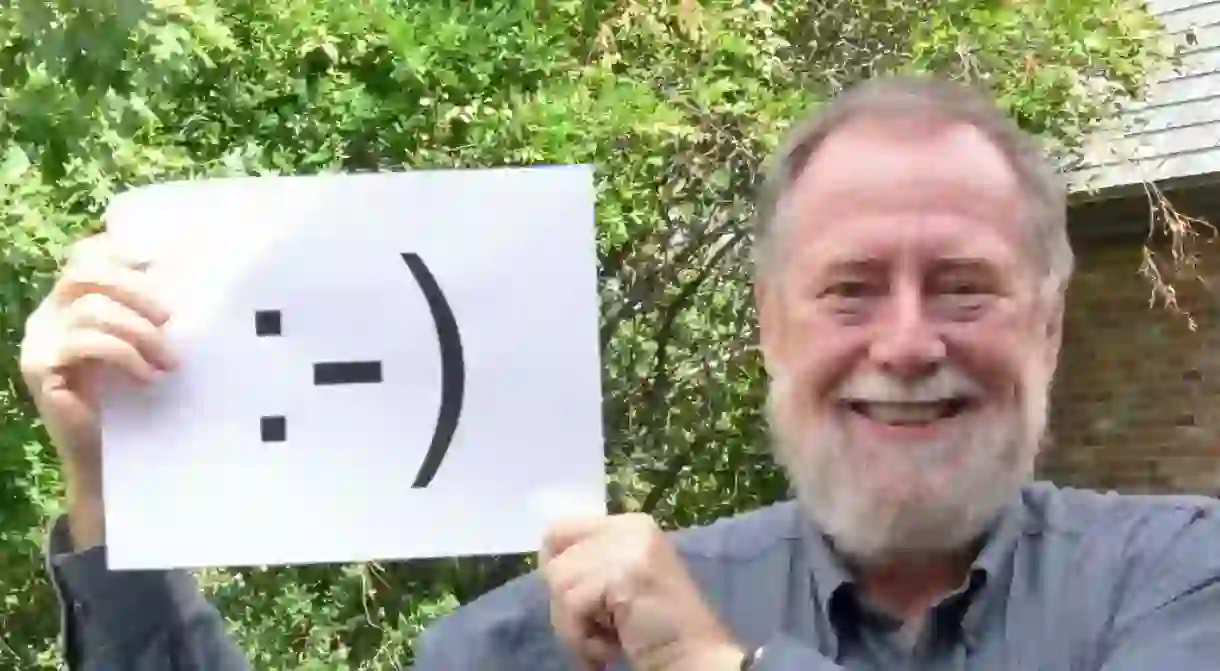

Meet Scott Fahlman, the Guy Who Created the First Emoticon

Those emojis you use every day—they started somewhere, you know, as emoticons. No one is exactly sure when the first one was used, but Scott Fahlman, a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was the first to suggest using it in messages sent on computer networks. Let’s meet Scott and learn about his pop-culture phenomenon.

In the early 1980s, the Internet was a far cry from what it is today. Computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee is credited with inventing the World Wide Web—building upon the work of dozens of pioneering scientists, programmers, and engineers that created the Internet. But prior to the www, email was in its infancy, and online bulletin boards (or bboards) were becoming more popular, connecting faculty, staff, and students in a forum of discussion about—anything, really.

There weren’t the emojis we know today to express sarcasm or humor, so the messages were oftentimes misconstrued. What was serious? What was sarcastic?

Nobody was really sure.

That’s where Scott Fahlman entered the picture. Scott was a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, and in the midst of a discussion on how to fix the dilemma, Scott inadvertently created a phenomenon: the first emoticon, a sort of sideways smiley face with two eyes and a nose. He also turned that smile upside down for a sad face, to express displeasure, frustration, or anger.

The historic day was September 19, 1982.

“We had local email and had just gained the possibility of email to a few other universities on the primitive networks,” Scott explained. “But this was text only, using only the U.S. English alphabet, so we didn’t have much to work with.”

The unique character sequences caught on quickly at Carnegie Mellon and proceeded to infiltrate computer network message boards at other universities and research labs around the world. Within a few months, different “smileys” emerged, and before long, there were dozens of them.

The open-mouthed, surprised smiley was one. A smiley wearing glasses was yet another. Eventually, there were noseless versions of Scott’s original creations.

“The noseless ones didn’t become popular until much later—I think in the 1990s,” Scott said. “I blame the bad keyboards on mobile phones, which made people try to type as little as possible, especially when it involved non-alphabetic characters.”

Then things got really creative when people with (apparently) too much time on their hands created emoticons that looked like Abraham Lincoln and Santa Claus.

Of course, there are those who argue that these so-called emoticons were used far before Scott created them in 1982. And Scott’s not discounting the likelihood. After all, he considers it a fairly simple and obvious idea.

Maybe teletype operators used them back in the day. Perhaps they were used in private letters long before the ’80s. The problem with those arguments is there’s no evidence. There is, however, proof of Scott’s original suggestion.

He didn’t keep the original post where he made the emoticon suggestion, largely because he didn’t think it was that big of a deal. But when the smiley face turned into a full-blown phenomenon, he knew he had to seriously look for it.

After some unsuccessful initial attempts, a friend of Scott’s, CMU alum Mike Jones (who was working at Microsoft at the time), organized and financed a sort of archaeological dig to find that original message on the university’s old backup tapes, searching and decoding ancient media to finally unearth Scott’s smiley-faced suggestion.

The proof was in the post.

“All I really claim is that I was—or seem to have been—the first to suggest using those original two emoticons in messages sent on computer networks,” Scott noted. “As to whether these were the first emoticons—a term that didn’t come along until later—it depends how you define it. It’s not really worth fighting over.”

That brings us to today. Scott is now professor emeritus at CMU, which means he’s formally retired, but he remains active in research, advising, and departmental activities.

And the original emoticons? Well, their fame lives on, but technology oftentimes intercepts them via content management systems and word processing programs, which turn them into little pictures 🙂 instead of the original character string. Scott feels it “destroys the whimsical element of the original.”

Nevertheless, he created something most everyone can say has become a part of their modern-day communicative life—whether in emails, text messages, or even handwritten letters. The emoticons evolved into a culture all their own, spawning animated renditions, and replacing written words.

How does he feel about being such an influence on society?

“This was 10 minutes of my life, just part of a silly online discussion more than 35 years ago,” he admitted. “So, it’s kind of a strange thing to be famous for, but it’s fun to be a little bit famous for something. I’ve come to accept that no matter what I achieve in my career as an AI researcher, the first sentence of my obituary will talk about the smiley face invention. If I’ve prevented some online misunderstandings along the way, and if people have had fun with these things, then I guess that 10 minutes was well spent.”