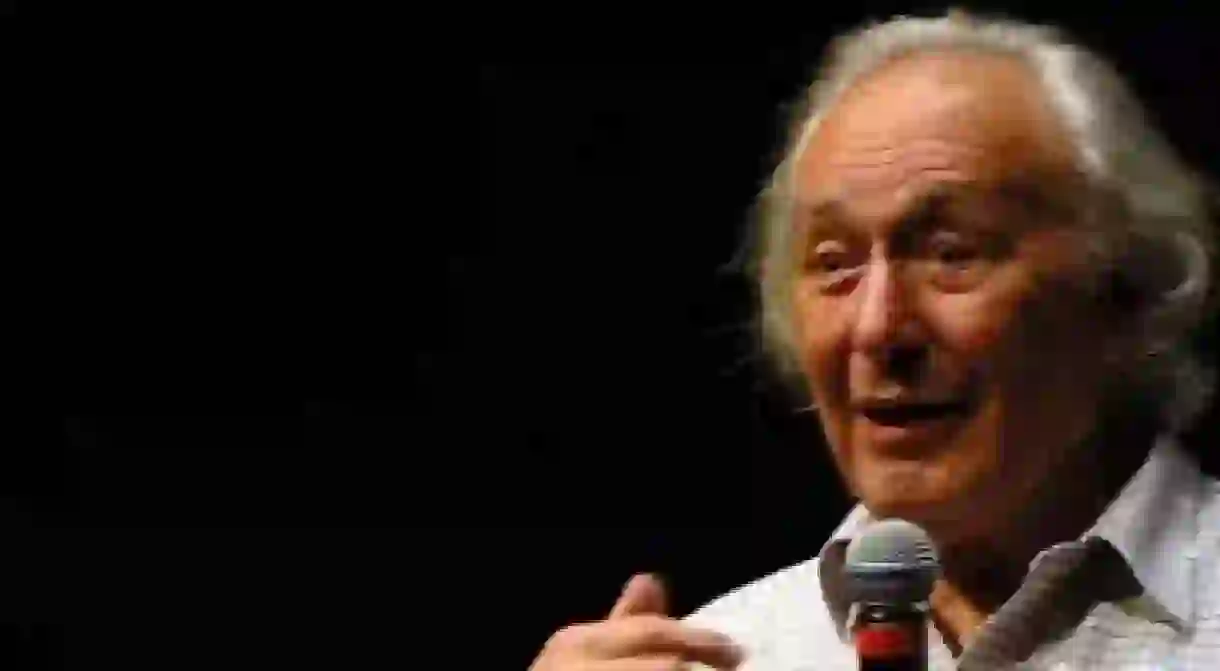

William Klein: Avant-garde New York Photographer

Street and fashion photographer William Klein’s avant-garde photography in the 1950s fundamentally changed the medium. One of the most influential photographers of the 20th century, Klein got up close and personal with his subjects, utilizing unique shooting techniques to create gritty, energetic images of city life.

A painter, sculptor and filmmaker, Klein came to photography almost by accident, but ultimately used his lack of training to his advantage. Unlike his contemporaries of the time Klein used a wide-angle lens and high-speed film, introducing grainy, blurry photos and completely setting himself apart from the existing photographic canons. In 1954, William Klein took his camera to document the streets of New York City. His gritty, distorted photographs showed a raw energy and technique that had yet to be seen, completely revolutionizing the art form.

Born and raised in New York, Klein spent many days as a child at the Museum of Modern Art. He graduated high school two years early at age 14, studied sociology at the City College of New York and served for two years in the United States Army. After the army, Klein enrolled at the Sorbonne in Paris with a grant from the American G.I. Bill, successfully escaping a future at his family’s law firm.

At the Sorbonne, Klein studied under the painter André Lhote but moved on quickly to the more progressive teachings of Fernand Léger. Léger preached a rejection of conformity and bourgeois values, and encouraged his students to look beyond their medium by going out and taking to the streets.

While living in Paris, Klein exhibited his paintings and sculptures throughout Europe. He created spare, abstract paintings and completed commissioned work for architects in Paris and Milan. Klein photographed a series of revolving black and white panels he created for an Italian architect, enjoying the distorted effect the movement created in the photo. Eventually Klein put the photos through enlargers, blurring the classic abstract geometric shapes into something new, and exhibited the photographs in Paris.

It was at this show in 1953 that Klein met Alexander Liberman, the Art Director of American Vogue, who was so impressed that he offered Klein a job in New York on the spot. Klein took Liberman’s offer and moved back to NYC in 1954.

Liberman gave Klein free rein with his photography, often funding Klein’s personal shots, but also contracting him as a fashion photographer for the magazine. Klein ultimately spent a decade shooting for Vogue and later photographed for magazines such as Vanity Fair, The New Yorker and Harper’s Bazaar.

Upon returning to New York, Klein turned to photography to help him understand the culture shock he felt. He had little experience, so he focused on capturing whatever he found interesting.

‘I was in a big hurry. Once I got used to everything in New York I knew the trance would wear off. So I took pictures with a vengeance’, Klein said. ‘I had neither training nor complexes. By necessity and choice, I decided that anything would have to go’. And it did. Klein opened his lens, took unfocused, grainy photos and often over-exposed the negatives. He told subjects that he worked for tabloid magazines, that their portrait would be published or become famous. He told them to pose, act out, do anything. His carefree attitude perfectly matched his impulsive photos.

‘Sometimes, I’d take shots without aiming, just to see what happened. I’d rush into crowds – Bang! Bang!’ Klein said. Klein was the epitome of how not to be a photographer, the complete opposite of the elegance and appropriateness of his contemporary, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and the photography world took notice. In a world full of talented photographers, Klein’s crude, sensational photography was a radical change.

“In the fashion pictures of the 1950s, nothing like Klein had happened before. He went to extremes, which took a combination of great ego and courage…He took fashion out of the studio and into the streets,” Liberman once wrote.

Klein was always attempting to get to the rawest, truest vision, giving his work in each city an innate sense of place and transforming viewers into intimate participants of the scene. In 1956 Klein published his first photo book of the city: Life is Good & Good For You in New York. By 1960, he published four other photography books, each dedicated to the street life of an international capital: Rome, Moscow, Tokyo and Paris.

In one of his most famous photographs, a young boy holds a toy gun close to the camera, his face threatening, twisted in anger. A younger boy stares at the gunman, already admiring his age and power. Klein told the boy to act tough, and snapped the photo in a second, without tie to aim or focus. “I was a make-believe ethnographer in search of the straightest of straight documents, the rawest snapshot, the zero degree of photography,” Klein said.

Despite this, Klein’s work wasn’t always well-received in America. His photos were uncomfortable, sensational and full of anger, significantly challenging the previous idea of a photo book. American publishers saw him as a fraud and his pictures Klein find literary success.

Just as he found international success, Klein turned away from photography for film-making, working almost exclusively on films from 1965 until the early 1980s.

Klein’s first taste of film-making came in 1957 on the set of Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria in Rome. Klein was invited by the celebrated director to work with him as an assistant and the pictures he took there during his free time ultimately became his Rome photo book. The work on set did influence Klein, however, and in 1958 he made his first film, Broadway by Light, an eleven-minute short. It is largely considered to be the first-ever pop film.

His second film, Who are you Polly Magoo? is a heavily satirical documentary on the fashion industry, though Klein still worked for Vogue at the time. Cheeky and cynical, Klein’s films nevertheless have heavy themes: the anti-war movement, American imperialism, government control and a profile film on the leader of the Black Panthers. Klein has directed over 20 films, mostly documentaries or satirical fiction.

The artist returned to photography in the 1980s after a resurgence of interest in his photographs. Throughout the 1990s he continued to work, creating mixed-media art, holding exhibitions across the world and conducting photo shoots in Barcelona, Paris and London.

He was awarded the Prix Nadar, the Royal Photographic Society’s Medal of the Century and Honorary Fellowship and the Outstanding Contribution to Photography Award at the Sony World Photography Awards in 2012.

Klein’s upheaval of the contemporary art scene made lasting ripples, influencing artists and photographers in a pervasive way. In 2012, the Tate Modern focused on the influence Klein had over other artists in a unique joint exhibition highlighting the work of Klein and Japanese photographer Daido Moryama, one of the most celebrated photographers of the Japanese Provoke movement in the 1960s. The exhibition considered the relationship between the style and work of the two artists. Klein’s explosive photos served as a powerful inspiration to Moriyama, particularly the photos in New York.

“I was so touched and provoked by Klein’s photo book, that I spent all my time on the streets of Shinjuku [one of Tokyo’s neighborhoods], mixing myself in with the noise and the crowds, doing nothing except clicking, with abandon, the shutter of the camera,” Moriyama said.

In 2013, 60 years since publishing the groundbreaking book, Life is Good and Good for you in New York was published, Klein returned to New York City to shoot Brooklyn. This time, however, his challenge was to shoot in digital. Working days and nights, Klein documented the streets of the ever-popular borough for his newest photo book, Brooklyn. It was recently celebrated at the Polka Galerie in Paris with an exhibit that covered every inch of the gallery walls with his Brooklyn images.

William Klein’s film-making and avant-garde photography introduced an entirely new photographic style as well as a new perspective on city life and fashion photography. Klein infused energy into contemporary photography and—at 88 years old—it seems he isn’t done yet.