William 'Boss' Tweed: Greed, Corruption, and the Expansion of New York City

William ‘Boss’ Tweed is a man often defined as the very symbol of cronyism and political corruption. Yet, there is far more to the story of Tweed than his greed. What lies beyond the underhanded schemes and smoke-filled backroom deals was a conundrum of sorts. By wielding such powerful influence to build and expand New York City, Tweed would use this same influence to swindle the city out of millions of dollars in a relentless attempt to impose both his political and financial might. This is a closer look at the menacing ghost of William ‘Boss’ Tweed.

William Tweed’s insatiable levels of greed coincided with a New York metropolis then undergoing rapid expansions in size, population, and financial opportunities. After the American Revolution and onward into the mid-19th century, the city’s economy centered around mercantilism. New York City was a major port city from its outset, and the overwhelming majority of its residents packed into Manhattan’s lower end. Yet as the New York population grew, so did its need for more land, economic opportunities, and public services. The city’s real estate was being developed at an explosive pace, and factories capable of producing a multitude of products sprang up everywhere.

Corona Brezina, author of America’s Political Scandals in the Late 1800s writes, ‘New York City grew larger. People crowded into areas that had been nearly empty. The narrow streets were packed. The city had to build more streets. More people needed homes, schools, and offices. They required new sewers and public transportation.’ It was this backdrop that allowed Tweed and his Tammany Hall cohorts to seize upon both financial philanthropy and political influence.

Ironically, William Tweed’s story begins in the harsh, poverty-stricken landscape of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. However, despite these humble beginnings, Tweed would gain complete dominance over all Democratic Party nominations before the age of forty. At its peak, this included the nominations of the mayor, governor, and the Speaker of the New York State Assembly. Brezina highlights, ‘Tweed knew how to get his way. He controlled voting.’

The ‘Boss’ began what came to be known as the ‘Tweed Ring.’ Though never a lawyer, Tweed opened a law office with the purpose of receiving payments from large corporations in exchange for ‘legal services.’ These services amounted to little more than using his various political contacts, through Tammany Hall, to award and secure favorable contracts to friends and business partners for a myriad of public and private projects. So quickly did his power and influence grow, that William Tweed was made ‘grand sachem’ of Tammany Hall by 1868, at the age of 45. Authors John Adler and Draper Hill, in their book Doomed By Cartoon, write, ‘Political, business, and personal friends, along with their relatives, were rewarded with real and/or fake positions.’

Even after buildings and other services were in place, William Tweed was able to continue bilking the city for more money through scams involving unnecessary repairs, overpriced goods and services, fake leases, and false vouchers. His voracious greed was beginning to soak the city dry. Tweed’s schemes are estimated to have swindled anywhere from $30-200 million, and his stranglehold on the city’s political elite allowed him to continue his dealings virtually unchecked. Adler and Hill write, ‘A major source of Tweed’s power came from his control over the nomination process. In exchange for office, politicians turned over patronage – granting privileges to him, thereby making both appointed and elected officials beholden to the Boss.’

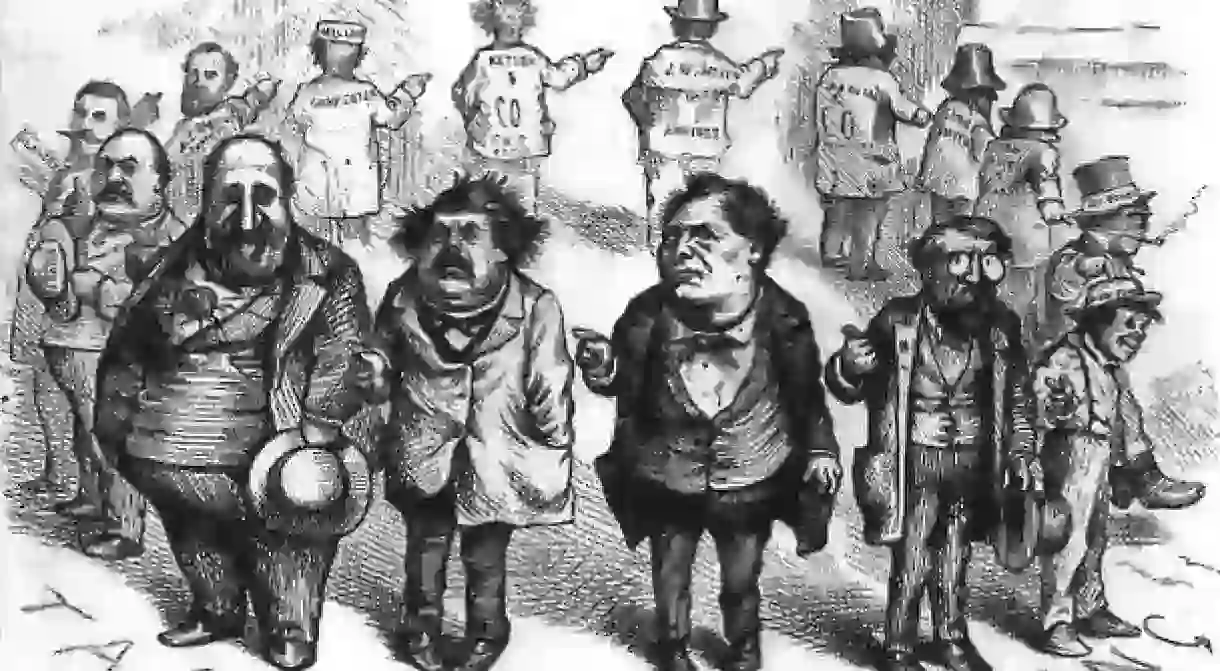

In the end, it took the efforts of the New York Times, and Thomas Nast, a political cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly, who waged a ceaseless campaign to expose Tweed and his cronies’ political corruption and greed. William Tweed was eventually convicted in 1873 of forgery and larceny charges. Tweed managed to escape from prison, and was able to flee the country. He was recaptured in Spain when Spanish police recognized him from one of Nast’s cartoons. Tweed was extradited back to the United States and sent back to prison where he died less than two years later from pneumonia in 1878.

There is no doubt that William ‘Boss’ Tweed was and remains the epitome of when the lines between the worlds of business and politics become blurred and even erased. At the pinnacle of his stranglehold upon the city, Tweed was considered the most powerful man in New York. Tweed, while issuing contracts and orchestrating projects to build and expand the city, threatened the financial and civic well-being of a city he was meant to serve. Even now, there are remnants of Tweed’s dealings still in existence today. And although Tweed was not the originator of schemes, he will continue to remain a constant reminder of the fallout when the division between politics and business gets muddied and all-too-conveniently intertwined.