This Exhibit Pays Tribute to an Iconic Brooklyn Rink as the Birthplace of Roller Disco

Roller disco disappeared from the pop culture scene almost as quickly as it blew in: The dance craze—or was it a sport?—was huge from 1978 to 1982. In its short life, it left a mark not just on the history of music but also on fashion, entertainment, and the Civil Rights Movement.

A new exhibit titled Empire Skate: The Birthplace of Roller Disco at the City Reliquary in Williamsburg brings the roller disco days back to life, and celebrates the role of Brooklyn’s Empire Skating Roller Rink.

Anyone who arrived in New York City after 2007 missed out on Empire Skate, as regulars liked to call it. But the Brooklyn hangout—which closed that year after 66 years in business–was, in its heyday, one of the places to be seen, or to simply vanish into a blur of thumping bass lines, skintight outfits and lightning-fast wheels. At Empire Skate in Crown Heights, on the site of the former Ebbets Field parking garage, amateur and professional skaters of every race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and class could show up and do their roller disco thing until dawn, to the sounds of everything from the Bee Gees to funk, soul, R&B and early hip-hop.

The inclusive vibe wasn’t all that common at American rinks at the time. The “godfather of roller disco,” Bill Butler, made his name at Empire Skate after moving to Brooklyn from Detroit, where his local rink—like many others in the 1940s—was segregated and only allowed black skaters in one night a week. Butler praised Empire’s “melting pot” crowd, in a time when groups including the NAACP were organizing skate-ins and protests nationwide to fight racial segregation at roller rinks. In its way, Empire Skate’s everyone-welcome vibe honored the spirit of pioneers like Ledger “Roller Man” Smith, who roller-skated nearly 700 miles from Chicago to Washington, D.C. in August 1963 to join Martin Luther King, Jr.’s March on Washington.

The City Reliquary’s Empire Skate exhibit takes up just a room and a half—the size of nearly the entire small museum—but it packs an impressive amount of memorabilia. Besides the dazzling disco fashions, you’ll find skating paraphernalia, historical posters and a summer skating-film series in the Reliquary’s backyard.

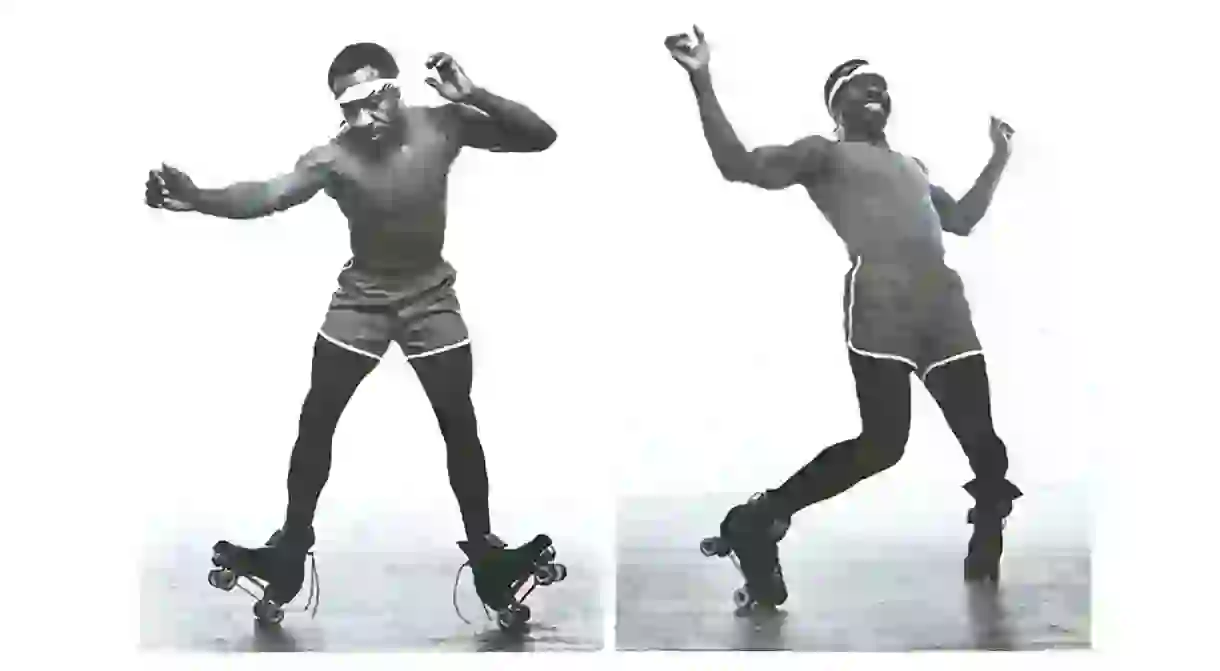

Indoors, the two video screens showing roller disco competitors doing dances like The Hustle and The Spank make it hard for visitors not to just grab the vintage rainbow skates out of the display case and bust a move. (Don’t do that: Instead, the exhibit tells you which roller rinks are open around New York City nowadays, doing their best to pick up where Empire Skate left off.)

Speaking of those vintage rainbow skates: The flashiest pairs of the era were designed by Goodskates, a company co-founded by Butler and designer Judy Lynn, which gets a nod in this exhibit. In Goodskates’s brief but dazzling life, Butler and Lynn launched a roller disco pop-up boutique at Macy’s selling glittery T-shirts and DayGlo leotards; consulted on the 1980 movie Xanadu, starring Gene Kelly and Olivia Newton-John; and opened trendy rinks like the Rollerballroom in Sag Harbor, Long Island.

Roller skating’s inroads into pop culture go well beyond roller disco, as the displays reveal: In the 1940s and ’50s, Empire Skate and others like around the country brought in crowds to do the foxtrot and waltz on wheels, and hosted Skate Queen beauty contests along with practice sessions for roller derby teams like the New York Chiefs.

Even if you’re just there for the roller disco nostalgia, it would be a shame to pay the Reliquary’s $7 admission fee (cheaper for college students, teachers and seniors; free for kids under 12) and not poke around the museum’s other quirky displays of New York City ephemera. You’ll find everything from antique Brooklyn seltzer bottles to a Statue of Liberty lightbulb and a collection of mislabeled NYC subway tokens.

The mission of the Reliquary, which launched in 2002 out of an apartment window at Williamsburg’s Grand and Havemeyer street corner, is to exist as a not-for-profit dedicated to preserving bits of New York City history that are otherwise easily forgotten. Certain relics may seem pointless to some (like a replica of a cake from a defunct bakery). But more ambitiously curated collections like the Empire Skate exhibit provide a valuable place where the small yet mighty players in the city’s history can shine on just a little bit longer.