The Story Behind Norman Mailer's New York City Mayoral Campaign

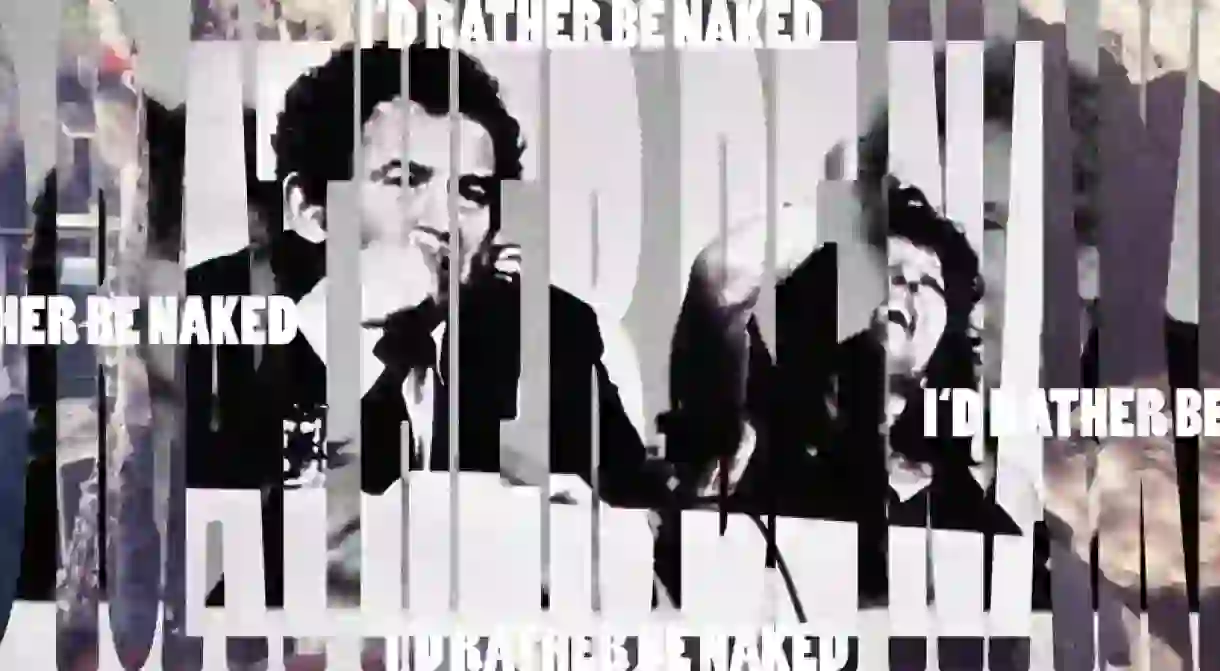

By 1969, Norman Mailer was an almost ubiquitous force in American culture. The author of 1948’s landmark war novel The Naked and the Dead had proved himself as a journalist, covering the Republican and Democratic National Conventions in 1968, a political theorist with 1967’s best-selling Why Are We In Vietnam? and as a countercultural icon, with the gonzo “nonfiction novel” The Armies of the Night. Politics was a natural next step. So, acting on the advice of Gloria Steinem (who was probably half-joking), Mailer entered the primary race for Mayor of New York City on June 17, 1969 with vociferous New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin on the “51st State” platform, which urged New York City to succeed from the rest of the state and become its own independent legislature.

That such an absurd prospect could enjoy any traction at all says a great deal about where New York was at the time. Rising crime rates would characterize the city’s 1970s nadir, poverty was widespread due to deindustrialization, and the middle class had largely left the city behind and decamped to the suburbs. The city’s political elite had stagnated, with Robert Wagner Jr’s administration offering little novelty or imagination when it came to setting the city to rights.

That was where Mailer came in. Besides secession, Mailer advocated for the banning of private cars in Manhattan, replacing them with cabs and a monorail system that would encircle the island. The new City-State would prioritize the elimination of pollution, reduction of government taxes, and total autonomy for the school districts, which might mean, according to the campaign literature “vest-pocket campuses built by students in abandoned buildings, restoring a sense of personal involvement that is lost in the large university campuses.”

Most notably, the Mailer-Breslin ticket proposed the creation of “Sweet Sundays,” which would mandate that all mechanical transportation would halt and elevators would close down so that, once a month, citizens could decompress from their busy lives without breathing in exhaust fumes. As unpalatable or unlikely as these policies might sound to us today, one of Mailer’s proposals was actually ahead of its time: a citywide supply of free bicycles that could be rented and returned at leisure.

Norman Mailer, however, had several disadvantages as a candidate. For one thing, he had been convicted of stabbing his wife in 1960, his campaign slogan was unprintable due to its coarseness (“No More Bullshit”) while another urged New Yorkers to “Vote the Rascals In,” and Mailer-Breslin campaign events were frequent fiascos (at one, the writer declared, that “The difference between me and the other candidates is that I’m no good and I can prove it,” and even referred to his own supporters as “spoiled pigs”). Still, the party won the support of the Black Panther Party after Mailer advocated for the release of their leader Huey Newton, and his self-styled party of “left-conservatism” would become a model for the Libertarian Party in subsequent decades.

To the surprise of all involved, Mailer did not come in last (only second-to-last), beating Charles B. Rangel and coming to represent the bitter divide between liberal and conservative parties in the state legislature – only in truly desperate climes would Mailer and Breslin actually look like viable candidates.

It was one of the first examples of a celebrity candidate and would be looked back on as, depending on your point of view, a 1960s lark, a serious blow on behalf of populism, or a disgrace. But the best quote probably comes from Jimmy Breslin himself who, upon learning that bars would be closed on election day, said, “I am mortified to have taken part in a process that required bars to be closed.”