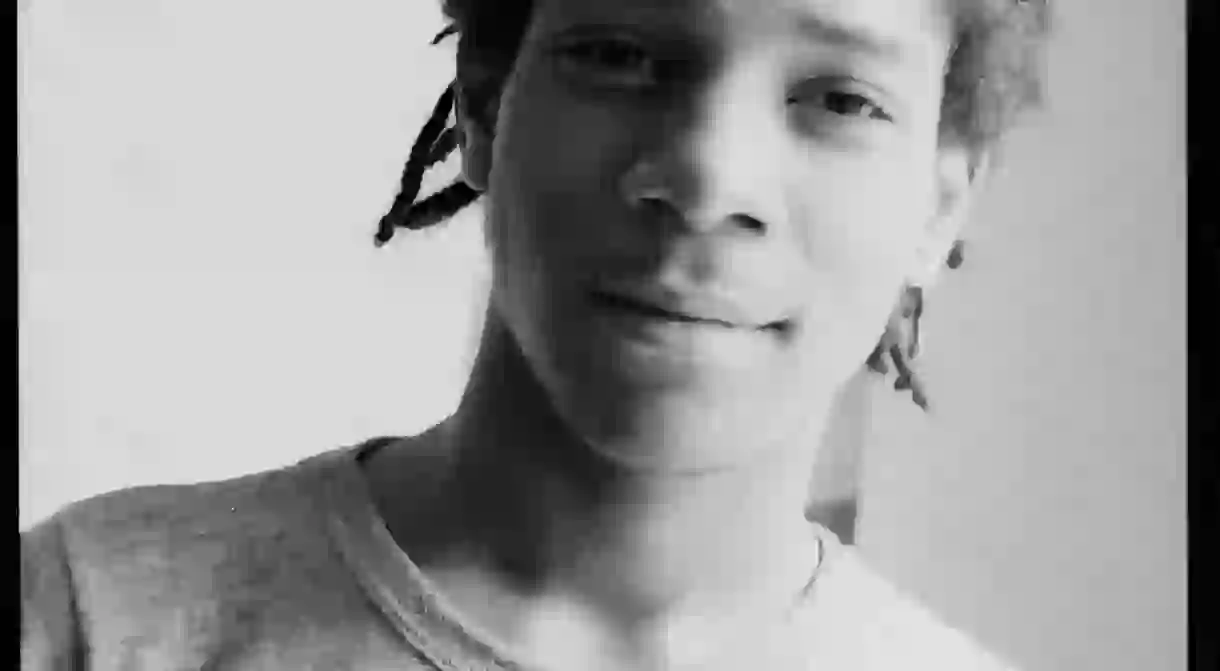

Sara Driver on Jean-Michel Basquiat: "It Must Have Been Like Living With an Elf"

Sara Driver’s vivid Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, now playing at IFC Center in Greenwich Village, is a revelatory documentary about the late artist’s early flourishing. Here are Driver’s thoughts on Basquiat and a unique period of cultural ferment.

Indie filmmaker Driver, best known for her magical realist drama Sleepwalk (1986), moved in the same Downtown New York artistic circle as the young Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960—88), the neo-expressionist and primitivist painter who would move like a comet through the American art world in the early ’80s once his genius was discovered.

The finding of a trove of Basquiat works and photos prompted Driver’s beautifully calibrated biographical film detailing the formative (albeit haphazard) years of the artist formerly self-tagged as SAMO. Boom for Real is especially cogent on how Basquiat drew from here, there, and everywhere—not least the ravaged East Village streets—when synthesizing his incomparable style.

Culture Trip: Did you know Jean-Michel?

Sara Driver: Yes. All of us working in art and film in the East Village knew each other. The streets were pretty dangerous so we stuck together as part of the same group.

CT: Did you know him as a friend or as an acquaintance?

SD: Just as an acquaintance. I’d see him and exchange a few words now and then.

CT: Why did you decide to focus on his late teenage years in Boom for Real rather than tell his whole story?

SD: My friend Alexis Adler lived with Jean-Michel in 1979—80. She was the first person to give him a key to an apartment where he lived. We all knew he had lived there as her roommate because of the mural on the wall and bathroom door. Everybody else would throw him out of their house when he would stay at their house and start painting their floor, but Alexis let him paint whatever he wanted. I teased her about it. I said, “It must have been like living with an elf.” She’d wake up in the morning and something would have been painted.

When Hurricane Sandy struck New York in 2012, Alexis suddenly remembered that she’d put away this work that Jean-Paul had given her and left in her apartment 30 years earlier. She was worried because the work was in a bank vault underground in the flood zone. She went over to the bank vault to check it out, and there was much more there than she remembered.

I went over to her house for a cup of tea about a month after the hurricane, and she pulled everything out that she’d found in the bank vault. She also remembered she had a box full of clothes that he had painted, and she also discovered about 150 photographs she had taken of him. Because Jean-Michel was so transient, little else had been kept from that period. Most people just threw out the stuff he’d scribbled on cardboard or pieces of paper, but Alexis kept it all. When I saw what she had, I realized it gave such an insight into him as a developing artist and into our city at that time. I thought, “Oh my God, I could make a 20-minute film poem about Jean at that time”. So I went out and bought a camera and just started shooting, and I made the film in much the same way as we made films back around 1980.

CT: And it eventually became nearly 80 minutes. Where did you get the footage of Jean-Michel?

SD: That’s [artist-filmmaker] Michael Holman’s footage. He and Jean collaborated on a lot of experimental Super 8 projects.

CT: When you knew Jean-Michel, were you aware at that time that he was a genius, or was it only in retrospect that you realized it?

SD: I think certainly Alexis was aware of it, which was why she kept all the work—not for its monetary value but as a keepsake and because she valued him and thought he was so talented. For example, there was the way he would write maybe two sentences on legal-sizedpaper and cross some words out but you could still read them; everything was very intentional. What I realized doing the film was what an advanced poet he was by the time he was about 18.

CT: The film strongly gets across that language was integral to his art. Do you think that was because he was naturally verbal, or because he was influenced by early graffiti artists?

SD: He was interested in words, interested in ideas. [Writer] Luc Sante said they would read the same things, including James M. Cain and William Burroughs. When you read Jean’s writing, it was very Burroughs-like—that whole idea of cut-up literature. And I think Jean’s choice of the words that he puts on his paintings are also what made him such an incredible artist.

CT: Was Jean-Michel as articulate in person as he was in his art?

SD: [He] was a well-spoken person and he wrote beautifully. What I discovered making the film was the caliber of people he was drawn to innately when he was 18. It’s like he picked his own university to attend, and a lot of the people he chose to be with were all recent Barnard and Columbia graduates. He was hanging out with Luc Sante, who’s such an incredible writer, hanging out with Jim [Jarmusch, Driver’s partner] and talking about film. He was hanging out with Alexis, who’s a scientist. I always wondered about the charts and graphs Jean-Michel put in his paintings, and it came as a revelation to me that they were taken from Alexis’s science books.

CT: I was surprised to learn how ambitious he was. Do you think it was fame that he craved or a more complex desire to be wanted, given that he came from a troubled background?

SD: I think it was probably both. If you talk to Fab 5 Freddy and Luc, you realize none of us were thinking about money. If we got a poem published in a magazine, that would be cool. But Jean really knew his value early on. It was kind of remarkable. None of the rest of us were thinking like that at all.

CT: It was typical that Andy Warhol should see the spark in him—Warhol being the figure from the previous generation who, above all, recognized the synergy between fame, art, and glamour.

SD: And Andy got a lot out of that relationship, too. It was a mutual admiration society. I like the collaborations they worked on.

CT: I sense some nostalgia on your part for Downtown at that time, which is perhaps inevitable since you lived through that period.

SD: Yeah, but the city has changed, and I’m a realist. A bunch of my peers and some of the artists involved with the film saw it at the New York Film Festival and everyone—including myself when I first saw the footage—had forgotten how burned out and how destroyed New York was at that time.

CT: Was it important to you that the film ended at the point when Basquiat was on the brink of major fame?

SD: Yes.

CT: It would have become a tragedy if you’d have gone on much longer, wouldn’t it?

SD: That story’s already been told. This is a story that hasn’t been told and has new insights into Jean-Paul. Once he became famous and had sycophants and drug dealers around him—and a whole spider web—it got quite ugly. He was so young and he had so much weight upon him. Jean was very sensitive, and I think he knew before the end what a commodity he had become, and that was very destructive to him as a person. The zeitgeist ended, too—the community of people working together at the end of the ‘70s and early ‘80s—so it just seemed the right spot to end the story.

The city started changing after that. We has an unnamed disease that was mysteriously killing people—AIDS—then there was Ronald Reagan. I was thinking recently how those times echoed now: then we had a B-actor President and now we’ve got a reality TV President. We are on the verge of a Cold War now; we were then when Russia invaded Afghanistan. Not only this city, but the world was a very dangerous place at that time, just as it is now.

CT: Are you positive about the current art scene in New York?

SD: Some really interesting things are happening. I was just in touch with Lauren Jones, who runs the Barter Art fair with young artists in Britain where you can’t buy art with money—it’s only bartering. And we have Spring Break Art Show in New York, which was started by Ambre Kelly and Andrew Gori in 2009. They take over abandoned spaces every spring at the same time as the Armory Show, and it’s grown substantially. It’s really the grandchild of the Times Square Show [where Basquiat exhibited in June 1980].

CT: Do you know what you’re going to do next, Sara?

SD: I have a few different projects. I’ve always been more of a narrative filmmaker but there’s a kind of freedom with shooting documentaries that I really appreciate. I know so many interesting people, some of whom are older and may not be with us very much longer, and I’d like to do a series of essay films on them. I also want to do a live-action film for children because there aren’t any anymore—it’s all Pixar, which gets kids ready for video games rather than cinema.

CT: And you have a project in mind?

SD: Yes, it’s based on seven metamorphoses tales from around the world. I’m also very interested in effects that you can do in the camera with light and shadow, instead of all this computerized stuff. Mythology and folktales inform us of other cultures, and I think it’d be cool to do a book of the original stories and the adaptation and how the effects were achieved—because kids are so interested in all that.