Million-Dollar Dirt: Digging Into Walter De Maria's Cryptic 'New York Earth Room'

Whether you extract significance from the distinct scent of earth, the muggy warmth of still air, the rare hush of near silence, or the curious juxtaposition of the natural with the urbane, the experience that is The New York Earth Room is, with the right mindset, an extraordinary one. In the 1970s, pioneering conceptual artist Walter De Maria created a 3,600-square-foot sanctuary that, with the exception of some vegetation and a few critters throughout the years, has withstood the test of time and essentially remained the same.

A renewed longing for sublime beauty would foster the 18th-century concept of the Picturesque. The idea was first articulated by the English artist, author, and clergyman William Gilpin as “that kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture,” but the term would evolve to delineate an experience—the delight taken in stumbling upon remote, forgotten relics.

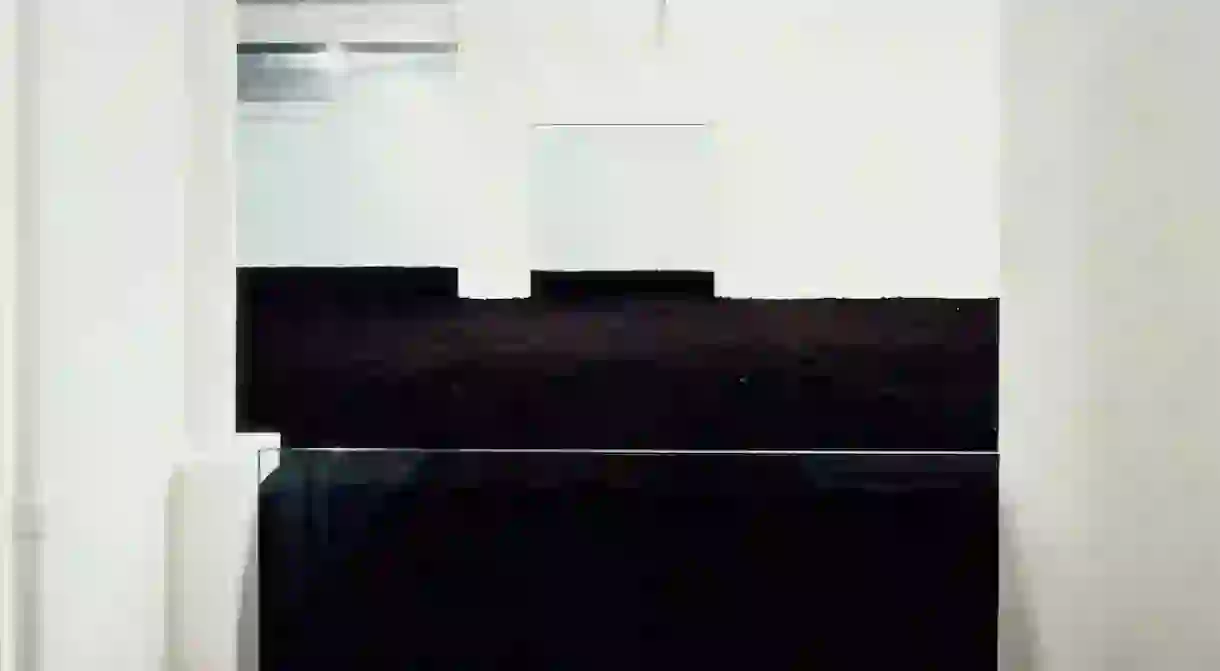

Walter De Maria’s The New York Earth Room (1977) feels like a modern exemplar of Gilpin’s musings, which in essence describe the entanglement of artistic and natural splendors. For 41 years, this peculiar installation—280,000 pounds of soil flooding the second floor loft of a Soho walk-up—has quietly endured. The artwork is a known entity among savvy New Yorkers, but without signage or fanfare or promotion, experiencing The New York Earth Room is like finding an architectural ruin. It’s there for a reason, but that reason isn’t immediately manifest—you’re left to create one for yourself.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BDEKy90BZNk/?taken-at=873383

The New York Earth Room lives at 141 Wooster Street. Buzz up, ascend a flight of stairs, hang left, and lo: a spacious would-be residence filled from wall to wall with clumpy dirt. You won’t find a plaque or label explaining what it all means. Photography is not allowed, presumably to keep ruthless Instagrammers at bay, so you may only document the artwork by taking the time to look at it. Those who visit do so out of genuine curiosity, and those who appreciate it have ruminated on its mystique.

Bill Dilworth is one such devotee. The loyal keeper of The New York Earth Room, Dilworth has been tasked for three decades with maintaining the installation. He waters and rakes it every day. In the past, the soil has cultivated life—from mushrooms to grass, even dragonflies. According to Dilworth, it’s too devoid of nutrients for anything to grow anymore. But his long-lasting position as its caretaker proves that The New York Earth Room, though it may appear static, is paradoxically—if only subtly—ever-changing. It provides a reprieve from the urban world just outside.

The New York Earth Room transports viewers to a plane of existence in which otherwise prime real estate has been (seemingly) long abandoned, half engulfed by the sands of time like an urban iteration of the Namibian ghost town of Kolmanskop. There, smack in the middle of Soho, you feel as though you’ve discovered a strange secret—and there, you pinpoint the air of distant nostalgia that Gilpin and his cohorts sought to illustrate. The surreality conjured by 140 tons of soil where soil doesn’t belong adds a layer of whimsy; yet De Maria’s use of raw earth means that every visitor can connect with the material in some way.

“The writers of the Picturesque delight in found objects, and court nature precisely because among its inexhaustible riches there lies ‘some accidental rough object,’ as Gilpin put it, ‘which the common eye would pass unnoticed,” wrote Stephen Copley and Peter Garside in The Politics of the Picturesque (1994). “Such objects are in essence ordinary and non-monumental, but their ordinariness is often transitory and unstable.”

What could be more ordinary or less monumental than soil?

Walter De Maria bequeathed no context or explanation of his work. The Dia Art Foundation, which owns the installation and oversees its maintenance, provides minimal information on their website, save a few logistical specs. But De Maria understood the transformative power of context. At the vanguard of 1960s minimalism, conceptualism, and land art, the California-born, New York-based installation artist manipulated perspectives of grandeur and space.

Approach it differently, and what is more profound or more promising than soil?

In his lifetime, De Maria rarely gave interviews. He wanted people to see his art first-hand, not read about it or look at it in photographs—because to see The New York Earth Room in only two dimensions would obliterate its depth and poignancy. But in a rare interview granted for the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art in 1972, he explained: “The most beautiful thing is to experience a work of art over a period of time.”

The New York Earth Room has persisted as one of the city’s longest-lasting permanent installations, and it can mean anything you want it to mean—even nothing at all.

The New York Earth Room is on permanent view at 141 Wooster Street, New York, NY 10012.