John Lydon Interview: Sex Pistols, PiL and Brexit

England’s one-time “antichrist” analyzes the life and times of Public Image Ltd, subject of a new documentary.

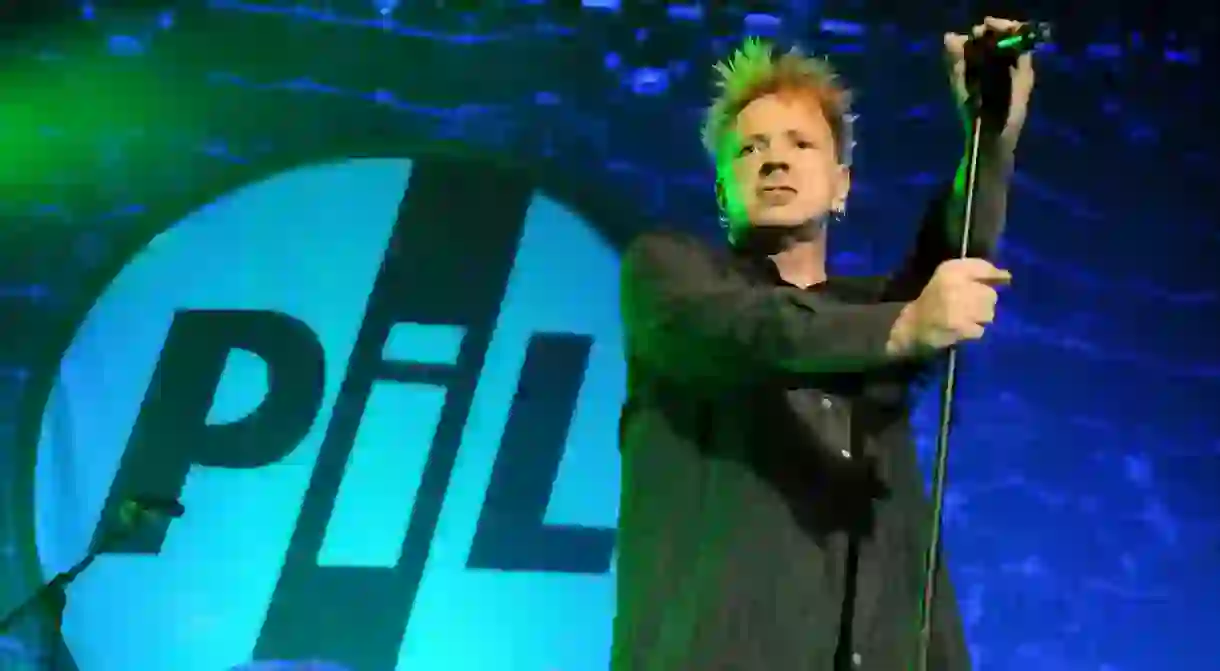

John Lydon – formerly Johnny Rotten – has for 40 years been the leader and one constant member of Public Image Ltd, the experimental post-punk combo he formed following the demise of the Sex Pistols. Lydon recently took time out of PiL’s current tour, which arrives at Brooklyn Steel on October 15, to chat about The Public Image Is Rotten. Tabbert Fiiller’s documentary details Lydon’s early life and his career after the Pistols, from his boyhood affliction with meningitis through every PiL configuration. Whereas Johnny Rotten was sardonic and provocative when talking to the press, Lydon these days is funny, wise and reflective. He still has plenty of ire, however, for priests and politicians.

Culture Trip: Are you psyched for your Brooklyn show?

John Lydon: I love the live gigs. When I was younger, I’d sort of be very wary and terrified. I’m not like that anymore. I’m very eager to get on stage because I completely trust the people I’m with [Lu Edmonds, Scott Firth, Bruce Smith]. It’s quite different, but there’s still the same excitement.

CT: You say in The Public Image Is Rotten that you couldn’t wait to start another band after the Sex Pistols. It made me wonder what positives you took from the Pistols experience.

JL: I learned how to adapt words to music. I hadn’t done anything like that before, and I’d never made any attempt at singing. So I’m eternally grateful. Those boys helped me, and I hope I helped them. I will never forget them. They’re special to me. The idea of being able to evolve a voice around somebody [Steve Jones] learning guitar was probably the best thing that could ever have happened to me. This is why I don’t have a snobbish approach to perfection in music, because sometimes the errors allow you to get to much more serious places in your heart emotionally than if you were just rigidly following set patterns, which is the trouble with modern music and all music, actually.

CT: You made quite a radical shift from playing three-minute punk songs with the Pistols to the almost avant-garde, anti-rock music you started making with PiL, especially with the Metal Box album.

JL: I was writing songs like ‘Religion’ when I was in the Pistols, you see. All the negativity about it was very strange. The only person I could get interested in it was Sid [Vicious], and he could not play two notes of it. But so what? We still would have got there. But the others [Jones and Paul Cook] just wouldn’t back up that kind of approach. There was an emotional weakness in the Pistols, I always thought, starting with the management – not knocking Malcolm [McLaren], because I don’t knock the dead. He did lots of good things, but he was a bit of a coward when it came to really taking things on. You see, to me, the royal family [the Queen was the subject of the Pistols’ ‘God Save the Queen’] was nothing at all, but I wanted that Catholic Church skewered proper. And so I saved ‘Religion’ up for PiL.

CT: How do you evaluate the first PiL lineup [with Keith Levene, Jim Walker, Jah Wobble]?

JL: Great fun, but what a shame we couldn’t hold ourselves together. But then we had the record company pressure – and I’ve got to be honest with you, Virgin were never happy about who I chose for my first PiL. They made life very difficult. And then intrigue crept in and there were secret little rendezvous behind each other’s backs as to who was a genius and who wasn’t. And [the others] were just too young to handle all that. I’d dealt with that in the Pistols. I’d watched Sid dismantle with the same kind of influences. And I warned these chaps that this is what would happen, but, no, people don’t want to listen. And so there’s destruction, and that’s the saddest thing of all. And, of course, Virgin handling the purse strings was a nightmare. You try to get a regular wage for a band? I couldn’t ask people to hang around for a year with no money in the kitty. Everybody would want advances, including myself [laughs]. None of us are innocent. The budget for a year would be gone in three months. And then it was sell-some-furniture time. I’m the only one in PiL that ever invested any money into it, no matter what any of them say. Hello, I’m still waiting on a ham sandwich, fellas.

CT: Do you think by its very nature that being in a band has to be turbulent and divisive?

JL: It doesn’t have to be, but for me it kind of worked well that way initially. “Sweet are the uses of adversity” – obviously a Shakespearean reference. Not meaning to be dramatic about it, but that was the situation. And so I assumed that that’s how it would always be. PiL now is the exact opposite of that. We’re really good friends. We have bitter, intense arguments but not to the point of unraveling our camaraderie, and that is a huge difference. The writing style, of course, has changed but I think for the better. The last two albums, in terms of poignancy and clarity and transparency and openness and generosity towards our fellow human beings, are far more worthy. I’ve done the dark stuff.

CT: You’ve always been a stickler for the truth. It seems like a core principle of yours.

JL: Meningitis. You lose your memory. It takes you nearly four years to find out everything about yourself. Everything you’re told in that period, you absolutely rely on to be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but. And when you find out you’ve been lied to at any point in that period, that is a hurt you never want to inflict on another human being. I was born left-handed. Now I know in primary school, between the ages of five and seven, the nuns hated me for that. That’s a sign of the devil to them. Then I get meningitis and lose my memory. I come back to school a year later and they’re telling me I’m not left-handed. Now I didn’t know whether I was or not. I was lucky enough to be able to use a knife and fork, let alone know my own name. And to try to make me be right-handed was a cruelty to inflict on me. It hurt a lot, funnily enough. Why would they want to do that to me?

CT: Do you think in a perverse way that the meningitis gave you mental strength?

JL: Yes. I think it was the most helpful thing that could ever have happened. I forgot everything, but it was a clearinghouse of all that debris that might have led me into being, I don’t know, a stupid drug dealer or a mindless minicab driver. It got me looking at my life from the outside and realizing what I was looking at. This was when I was between eight and 11. You would think that would be a lot for a young kid to take on. No, that’s exactly the time to take it on. An adult would find a problem with that because we’re too damn complicated, you know? We’ve got egos and all kinds of agendas running rampant. A child is a sponge. It wants information. So lucky me.

CT: Do you regret the long break [1992-2009] that PiL took?

JL: It wasn’t of my asking, was it? That was a catch-22 there. [Virgin Records said:] “You owe us this much money. Until you pay that back, you can’t work.” I tried to outweigh it and outwait it, but, no, not one label would really give me the chance. And any way I raised money, [Virgin] would go, “Ha, that’s ours.” I thought that was very spiteful because there were a lot of bands in that period that were hooking on to the PiL idea, and it was painful to watch all the things that I’d been trying to do over the years being stolen. It hurt hard.

CT: Did you despair that you wouldn’t get the band together again?

JL: I despaired all through that. There’s despair in my entire career, constantly like, “Oh, there’s a pound note.” Snap! It’s on an elastic band. There was no support, no backup, which is why I turned down [the Sex Pistols’ induction into] the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. My old Sex Pistols friends were going, “Oh, how can you be so mean? It’s an award.” It’s not an award, man. These people fucked us over. They cut us off, right? Is there self-pity in this? No, because for every negative step put against me, I’ve got two positives.

CT: I don’t think it can have occurred to many people that the former Johnny Rotten could be nostalgic for all those things you sing about in the song ‘Human.’

JL: What kind of fool would not miss an English rose skipping in a floral dress across the lawn barefoot on a summer afternoon? Really, it is England, isn’t it? That beautiful vision. It might not be true, but we all have a memory of it. I’ve watched England kill itself slowly for far too long. And I don’t know how to help it anymore. It seems on a suicidal mission of self-destruction. I’m watching that now around the world politically. We really have come into the age of stupid.

CT: You’re referring to Brexit and Trump?

JL: What was the Brexit vote about? It was about too much immigration, period. And you’re not allowed to say that? Well, hello – everybody knows. I can’t live in a world where millions and millions of us are ensnared in this ridiculous box of not telling the truth in case we confuse or insult each other. The most insulting thing you can do as a human being is to not tell another the truth. Story of my life, transparency. Welcome to PiL.

The Public Image Is Rotten is currently screening at Metrograph, 7 Ludlow Street, New York, NY 10002. John Lydon will be present at selected screenings.