Explore the Wonder of New York City’s ‘Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth’ Exhibition

The Morgan Library & Museum’s show reveals how illustrations, calligraphy, invented languages and map-making were essential to JRR Tolkien’s authorship of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

JRR Tolkien (1892-1973), a venerable Oxford professor of Anglo-Saxon and English, was nonplussed by his latter-day fame as the immensely successful author of The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954-55). A private family man, he would have looked askance at a semi-biographical museum show, as he would have frowned on the blockbuster movie triptychs based on his books. At least the Morgan Library’s Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth is earnest in its focus on the symbiotic evolution of his invented languages, artwork and fiction. It’s also thrilling to behold.

Tolkien’s genius as a storyteller was complemented by his powers of description. So rich was his use of imagery that his readers need no visual aids to see in their mind’s eyes the mythical world of Middle-earth – especially when it comes to topography, different peoples and beasts, and war. Even the lore passed on in the stories – of the tragic lovers Beren and Lúthien and of the forging of the Rings of Power, for example – has a physical immediacy.

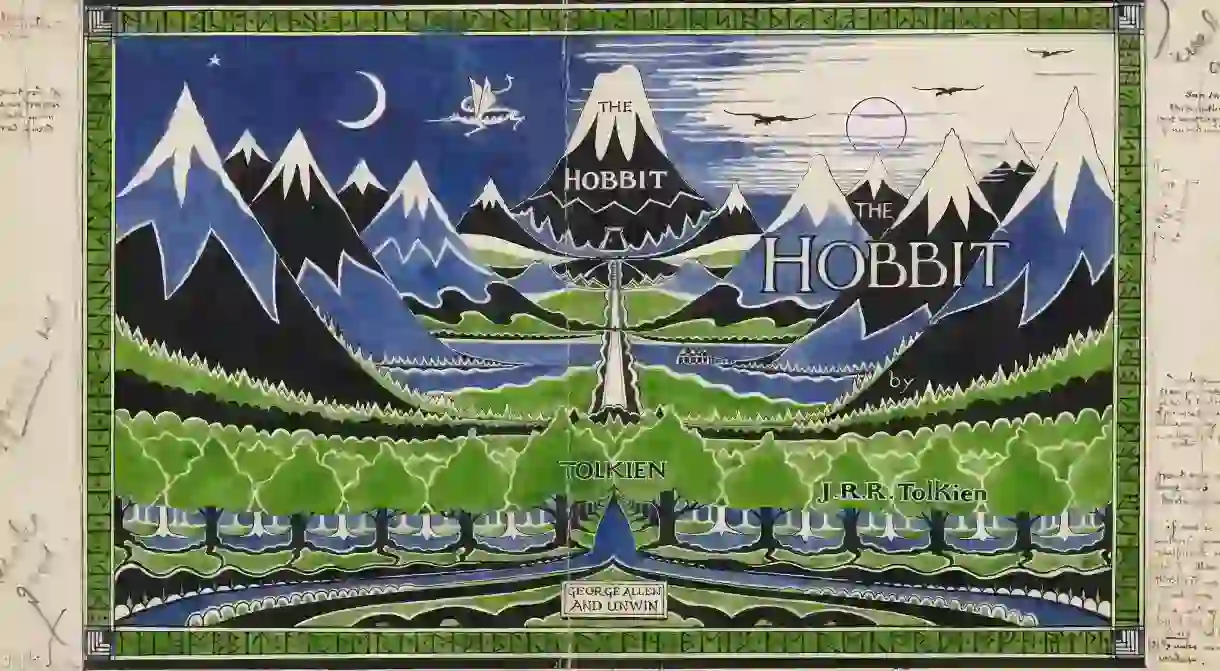

Yet Tolkien did supply six watercolor paintings for publication in the first American edition of The Hobbit, as well as two black-and-white ink drawings, an end-paper map and designs for the binding and dust jacket. For The Lord of the Rings, he created maps, the flowing Elvish script (distinct from the story’s text) of the words inscribed on the One Ring that the hobbit Frodo Baggins must destroy, and a drawing of the Doors of Durin – also adorned with Elvish characters – through which Frodo and his companions must pass.

These few pictorial elements are integral to the experience of appreciating the books’ atmosphere, which fuses the otherworldly and the Medieval, the spectral and the sinister. What the books don’t show is that, as Tolkien wrote them, he compulsively made hundreds of sketches to help concretize his ideas. The exhibition in the Morgan’s Engelhard Gallery – which combines Tolkien’s personal history with a chronological account of how his Middle-earth mythology evolved – enables the public to see many of these delicate artworks for the first time.

Via paintings like the 12-year-old Tolkien’s bucolic 1904 watercolor Alder by a Stream you can trace how the rustic life of the hobbits and their Shire homeland emerged from his perceptions of “the central Midland English countryside,” where Tolkien and his younger brother, Hilary, born in South Africa to English parents, were raised after their widowed mother brought them back to England. Some Middle-earth sketches have stylistic antecedents in his early renderings with ink, paint and pencil, and even echo the magically illustrated Father Christmas letters Tolkien made for his and his wife Edith’s four children between 1929 and 1943.

One of the precious artefacts on display is Tolkien’s ‘The Book of Ishness’ (1914-28), a sketchbook of experimental paintings, some Abstract Expressionist in style, some inspired by the Finnish Kalevala legends, some designed symmetrically – as would be his dust jacket for The Hobbit. The show meanwhile explores the visual and linguistic development of The Silmarillion (initiated in 1914, published posthumously in 1977), The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. One of the designs Tolkien made for The Return of the King dust jacket shockingly features a spiky-haired Sauron, the Dark Lord of Mordor, who remains undescribed in The Lord of the Rings.

Enlarged on a wall and adorning the cover of the exhibition catalogue is Bilbo Comes to the Huts of the Raft-Elves. It was Tolkien’s favorite of the watercolors he painted for The Hobbit – he was disappointed when the US publisher, Houghton Mifflin, omitted it from the book. Writing to the publisher in 1938, Tolkien regretted that the book’s minders “did not select the River-picture in which on the whole the amateur artist caught the imagined scene most closely.” Despite this puff of annoyance, Tolkien was self-deprecating about his artistic skills. Always a perfectionist, he scrawled on the back of one eerie sketch of Dunharrow – the mountain-field that leads to the Paths of the Dead in The Return of the King – “No longer fits story.”

The exhibition provokes many unanswered questions, which should intrigue Tolkienites young and old. The more one delves into Tolkien’s intricate Middle-earth legendarium, the more mysteries it yields. The very mystique of the Norse- and Finnish-derived place names on Tolkien’s crowded early Silmarillion maps, drawn in the 1920s and 1930s, prompts speculation on what skirmishes or occult deeds occurred at, say, the coastal Tower of Tindabel or on the Hill of Spies.

For that matter, looking at an 1895 photograph of the toddlers JRR (John Ronald Reuel) and Hilary, one marvels at their blond candy floss hair. When their mother Mabel described the 14-month-old Ronald as “a fairy when he’s very much dressed up” and as “an elf” when “he’s very much undressed,” did she plant a literary seed for Tolkien’s elf lore? With its elegant curlicues, the handwriting in her letters clearly influenced Tolkien’s Elven scripts. Widowed at 26, Mabel homeschooled Ronald and Hilary until she died at the age of 34. “My interest in languages was derived solely from my mother,” Tolkien wrote in 1967. “She was also interested in etymology, and aroused my interest in this; and also in alphabets and handwriting.” Mabel taught him to draw, too.

It comes across forcefully in the show that Tolkien’s great saga was founded on languages he’d already devised (if not completed) and maps he continued to work on. In 1915, shortly before he was to fight in the battle of the Somme, Tolkien began a process lasting over 50 years in which he elaborated and revised “a family of invented languages, which can be collectively called Elvish tongues,” writes Carl F Hostetter in the catalog.

Tolkien’s tales, begun in late 1916 when he was recuperating from trench fever in England, were fitted to the languages, not vice versa. “The imaginary histories grew out of [my] predilection for inventing languages,” he wrote. He discovered “that a language requires a suitable habitat, and a history in which it can develop.” A “family tree” of 23 tongues of Middle-earth, handwritten on a sheet of paper in 1936 and included in the exhibition, hints at the scope of his philological ambitions.

After Tolkien retired from academia in 1959, he spent more time completing (without fail) the crossword puzzles of The Times and the Daily Telegraph. As he pondered the answers, he doodled on the newsprint scrolls, friezes and paisley motifs. Some of these beautiful designs – 183 survive, and a selection are at the Morgan – were incorporated into Tolkien’s legendarium, resembling as they do the brooch-like designs he created for the lost island of Númenor west of Middle-earth. It seems that virtually nothing Tolkien did with a pen went to waste.

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth continues through May 12, 2019, at the Morgan Library & Museum, 225 Madison Avenue at 36th Street, New York, NY 10016. Tel: +12126850008. visitorservices@themorgan,org. The accompanying book, edited by Catherine McIlwaine, can be purchased from the museum store or Amazon.