Does "The Handmaid's Tale" Predict the Future, or Is It Alarmist?

The Handmaid’s Tale, currently streaming on Hulu,is the most chilling television drama of the Trump era so far.

Show-runner Bruce Miller’s 10-hour dystopian thriller imagines a future in which population growth in America is dependent on state-organized rapes. The commandeering of fertile women as breeding stock for insemination by members of the ruling elite in a neo-Puritan version of animal husbandry reeks of the Nazi S.S.’s eugenicist Lebensborn program and invokes, too, the memory of Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the Soviet secret police under Stalin—and the Politburo’s rapist-in-chief.

Elisabeth Moss, brilliant at playing dissimulators, is mesmerizingly sly and sarcastic as the story’s breeder protagonist, the frightened former book editor June, who trusts no one but is one determined to survive the regime in hopes of being reunited with her eight-year-old daughter. A flashback in the first episode reveals that June’s husband was shot, offscreen, by government goons.

There might have been wonderment in Moss’s voice when she remarked in a Time magazine interview, “I get asked a lot whether the show is in response to the election, but we were filming beforehand.” Few who watch The Handmaid’s Tale, co-produced by Moss and Atwood and co-starring Alexis Bledel, Yvonne Strahovski, and Joseph Fiennes, will separate it from the Republican administration’s war on abortion rights and women’s health care.

Watching the first three installments reminded me of 1964’s It Happened Here, which grimly speculated how a Britain occupied by the Nazis would have coped with the imposition of martial law following a hypothetical Axis victory in World War II. Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo’s film conceded that collaborationism would thrive. Every tyrannized society produces its share of self-preserving informers and treacherous opportunists.

When the hypothesis “it happened here” is applied to The Handmaid’s Tale, it prompts the question “could it happen here?”—”it” being the ritualized oppression of women in an atmosphere of paranoia and dread akin to that of Stasi-policed East Germany.

Such an idea was risible when Hillary Clinton was leading the Presidential polls. America is a long way from becoming the theocratic Gilead of Atwood’s novel and the series. Yet Trump’s signing in April of a bill that allows states to withhold federal money from organizations, such as Planned Parenthood, that provide abortion services raises the terrifying specter of legalized Orwellian misogyny.

Adapted from Margaret Atwood‘s 1984 novel, currently number three on Amazon’s best-sellers list, the series is set in a post-apocalyptic, two-state America run by a totalitarian male theocracy that has exploited a fertility crisis and the rocketing of the infant mortality rate to inaugurate its program of ritualized rape.

A fascist coup coincided with the elimination of women from the work force and a gendered re-stratification of society, events that had been preceded by endemic slut-shaming and the vilification of female friendships. Because most women found they couldn’t conceive, those who could were tainted as immoral and treated little better than Jews in the early days of the Third Reich.

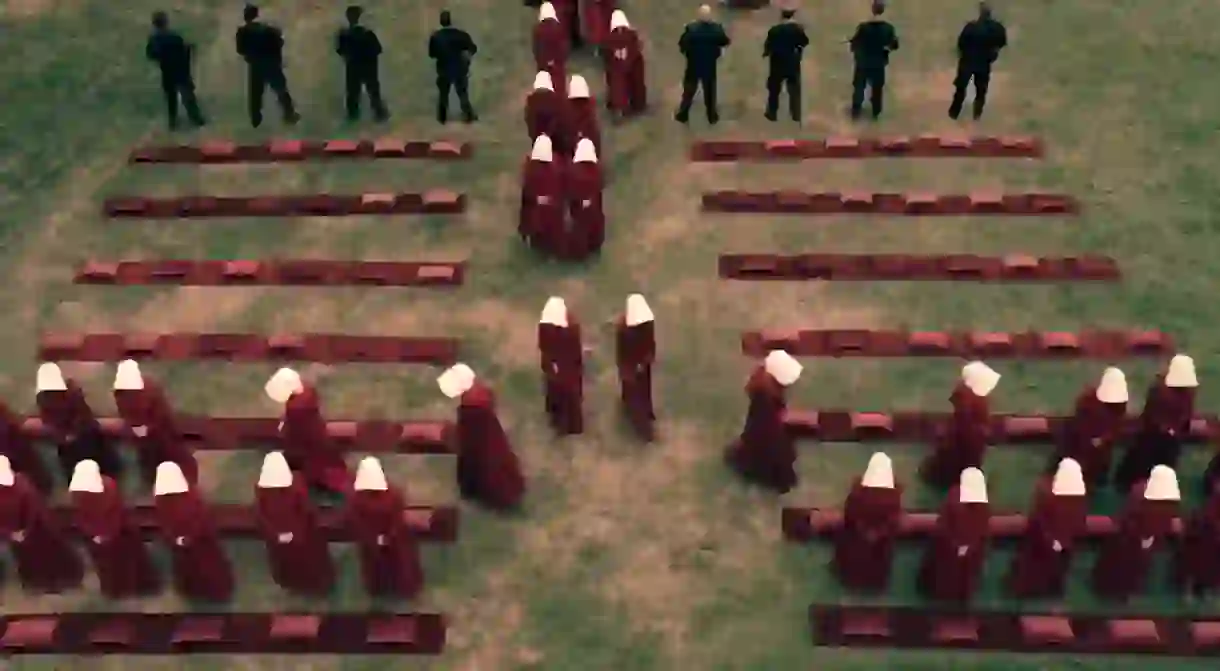

The small percentage of young women with healthy ovaries have been conscripted into a powerless class of surrogate mothers—”handmaidens”—whose job is to be impregnated by the ruling males and to carry to term the babies they hand over to the barren wives. When the breeder women conceive, enter labor, and give birth, the wives sit behind or around them, mimicking them like players in a pathetic charade. Breeders who rebel against the baby-factory rules are blinded in one eye.

Aunt Lydia (Ann Dowd), the warden who supervises the breeders, orders them to beat and kick to death a man who raped one girl. Lydia recalls the bull dyke matron (Valeska Gert) of the German girls’ reformatory in Diary of a Lost Girl (1929),director G.W. Pabst’s second vehicle for the American actress Louise Brooks. Gert’s character anticipated Irma Grese, the sadistic Nazi SS guard who worked at the Ravensbrück, Auschwitz, and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps.

June knew the world was changing when she and her college friend Moira (Samira Wiley) were evicted from a campus coffee bar by the man who had replaced the woman barista. That Moira is a black lesbian emphasizes the intersectional nature of the discrimination against women under the emergent Christian power.

The town in Atwood’s novel is a version of Cambridge, Massachusetts, the home of Harvard, which, she notes in a fresh introduction to the book was once a Puritan theological seminary. On the page and in the series, a wall near the Widener Library, the headquarters of the Gilead Secret Service, is used to display the corpses of executed dissidents. Renamed Offred (daughter “of Fred”), June and three fellow breeders rest by the wall during a shopping trip—several hooded bodies dangle above them a few feet away.

Why Harvard? From the 17th century onwards, Harvard men dominated the Massachusetts judiciary that sent thousands to their deaths at Cambridge’s Gallows Lot. They included three of the four slave-owning judges who notoriously condemned one convicted slave to be hung and another to be burned at the Gallows Lot in 1755. Chief Justice William Stoughton, who presided over the Salem Witch Trials in 1692 and 1693, had graduated from Harvard in 1650. The Handmaid’s Tale, partially Atwood’s response to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, visits a Salem of the near future.

“Is The Handmaid’s Tale a prediction?” Atwood asks herself in the new introduction. It’s a question that’s increasingly put to her, she writes, “as forces within American society seize power and enact decrees that embody what they were saying they wanted to do, even back in 1984, when I was writing the novel.”

She concludes it isn’t a prediction because “there are too many variables and unforeseen possibilities. Let’s say it’s an anti-prediction: if this future can be described in detail, maybe it won’t happen. But such wishful thinking cannot be depended on either.”

Atwood doesn’t mention McCarthyism, but that hysterical mid-20th-century manifestation of the Red Scare reminds us that conditions are always “right” for an empowered bully to exploit public hatred and ruin thousands of lives. The Handmaid’s Tale series is suffused with the aura of a new McCarthyism directed at women.

Anyone who doubts that wars have been waged against women in comparatively recent times should read Bram Dijkstra’s book Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture, which reveals how late 19th-century and early 20th-century art demonized female sexuality. Dijkstra’s subsequent book Evil Sisters shows how misogyny was a key tenet of anti-Semitism in Nazi Germany.

Pandora’s Box (1929), Pabst’s legendary first film with Brooks, aligns her promiscuity with her Jewishness, which is indicated by her owning a Menorah. Her pimp Schigolch (Carl Goetz), who may be her father and the first man she slept with, is portrayed as a Jewish homunculus. Brooks’s Lulu pay the ultimate price for acting on her sexual freedom. Forced, eventually, to become a prostitute, she takes a fancy to a handsome vagrant in the London fog and offers him a freebie. He is Jack the Ripper.

Atwood’s novel ends ambiguously, but not without hope. May Offred be spared a fate like Lulu’s. As played by Elisabeth Moss, she has become a symbol of resistance more important than the actor could have imagined.

Read Culture Trip’s Grace Beard here for more on The Handmaid’s Tale.