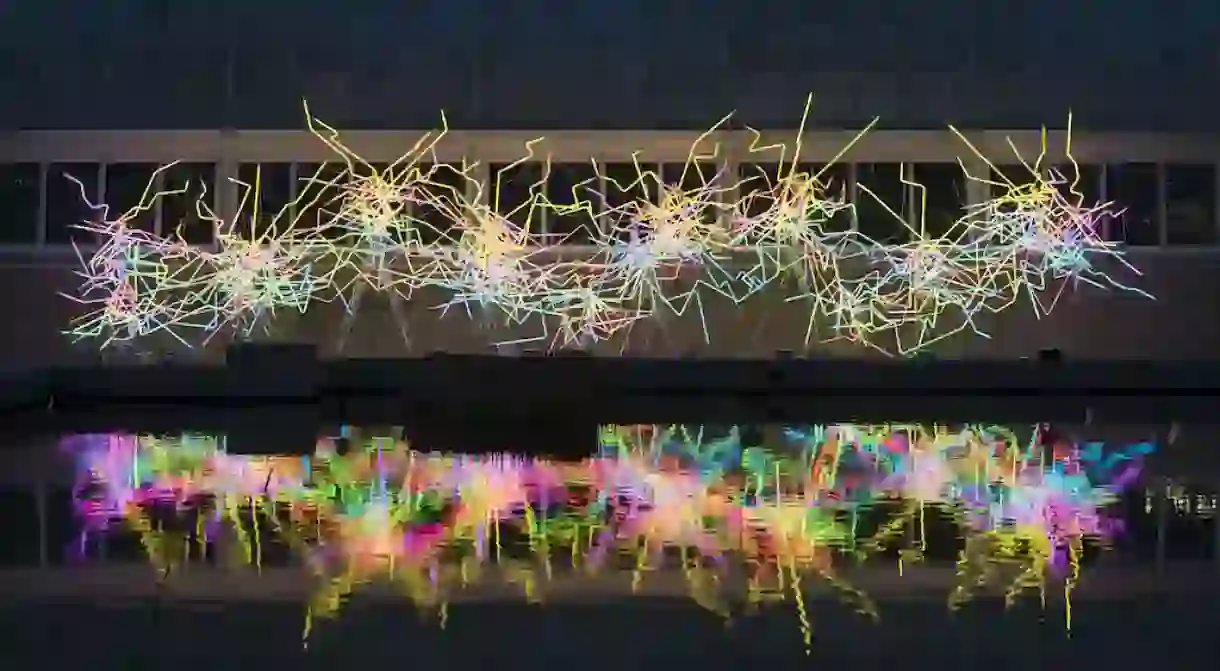

Dale Chihuly's Glass Sculptures Dazzle at the New York Botanical Garden

On April 22, the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) unveiled CHIHULY, a stunning survey of arresting sculptures by America’s premiere glass artist.

After more than a decade, Dale Chihuly has made a triumphant return to NYBG. CHIHULY features more than 20 sculptures across the garden; curated in the conservatories, towering over the surrounding flora, and showcased in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library Building. The artist spoke to Culture Trip about his new landmark exhibition, and the extraordinary medium he’s mastered over his 50-year career.

Culture Trip: What was it about the material’s properties and the glassblowing method that inspired you to dedicate your career to this medium?

Dale Chihuly: Within the first few weeks of my working with glass, I started working with the organic aspects of the liquidity—the natural sort of watery, liquidy qualities of the material. Glass is [one of] the only material[s] that’s really transparent. So it’s the only material that you can send light through. Everything else you have to light the surface of. But glass can not only be transparent, it can be translucent, it can be opaque. It’s an extraordinary material.

And so when you’re working with transparent materials, when you’re looking at glass, plastic, ice or water, you’re looking at light itself. The light is coming through and you see that color—that cobalt blue, that ruby red, whatever the color might be—you’re looking at the light and the color mix together. Something magical and mystical; something we don’t understand, nor do we care to understand. Sort of like trying to understand the moon. It has magical powers, water. And glass has magical powers. And so does plastic. And so does ice.

CT: Can you explain your glassblowing technique?

DC: The whole idea of making art, as far as I’m concerned, just comes from doing it over and over and over. Finally you’ve just done it so many times that it becomes sort of natural. But you’ve got to go through five or 10 years of making mistakes all the time before you can develop that. It’s tough because I fail a lot. I mean, I really question my own aesthetics a lot of times. I’ll make something and really like it, and then a couple of months later not like it. It’s embarrassing sometimes, but, you know, if you’re going to get good, you’ve got to do it.

I very often push a series to its maximum size. I think sometimes I do it just to keep the glass blowers at the very edge of the technical ability, to keep the tension high, to make it exciting, to make it so that we don’t know whether it’s going to break or not break.

CT: Have you kept your technique traditional, or would you say you’ve changed the game over the course of your career?

DC: The technology really hasn’t changed—we use the same tools they used 2,000 years ago. The difference is that when I started, everyone wanted to control the blowing process. I just went with it. The natural elements of fire, movement, gravity and centrifugal force were always there, and are always with us. The difference was that I worked in this abstract way and could let the forces of nature have a bigger role in the ultimate shape. And, another way I have changed is that I work with teams. When I started, no one in America was working with teams, but when I visited Europe, the glassblowers there worked in teams and they were able to do things that would be impossible alone. And I have been able to do so much more because of my team. Some of them do their own artwork and they are highly skilled, and together we can make my work on a much larger scale and push boundaries, which is what I like best.

CT: How long does the glassblowing process typically take for installations such as those in the garden?

DC: It took three years to prepare the exhibition for NYBG. The glassblowing process is more or less complex and time consuming depending on the size of the work and the number of elements.

CT: What elements of nature inspired your work in this show?

DC: My forms are made in a very natural way so they look like they come from nature. But I don’t look at pictures of plants and say, “now I’m going to make one that looks like this.” Perhaps that’s one of the reasons they work in a greenhouse and work with plants; because they don’t really look like the plants that are there, but they complement the plants that are there. The greenery compliments my work.

CT: How do you know when a piece is finished?

DC: I think an artist knows often when they hit on something. In fact, an artist really can’t move ahead or go on unless they have that feeling. Sometimes, you might have to fool yourself that you are doing something important but unless you can make something important, you can’t continue.

CT: How do you hope your artworks will enhance and transform their surroundings?

DC: My hope is that my work here gets people who are interested in gardens and greenhouses to become interested in art, and vice versa. Lots of people are missing out by not going to conservatories—the majority of people, probably—but once they get inside one, it’s another world.

CT: Have any artists or designers significantly inspired your work?

DC: I would have to say Van Gogh. And Andy Warhol was a big influence on me. He was alive when I was younger and I once traded with him. He wanted one of the pieces in my gallery and I was glad to do it. He has done so many things and influenced a lot of creative people. I just find his work very interesting and it has made a lasting impression on me.

Also, Christo and Jeanne-Claude are among the artists that inspired me the most. I really connect with their projects and the way they do them. Some time ago, I saw one of the documentary films about one of their first big projects, called Rifle Gap in Colorado. The concepts seemed like such a unique undertaking. We went to Berlin when they wrapped the Reichstag. They had 1,200 people working on it. And they always complete whatever they start. I don’t think anybody else could do it. It’s so amazing and I really admire them. In many ways, what I do is a smaller version of what they do. For example, the Chandeliers that we suspended all over the canals of Venice were a similar idea to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Gates in New York’s Central Park, since they complement natural surroundings.

CT: How would you say your career has evolved over the years?

DC: It would take all day to answer that question—I am 75 and have been a working artist for more than 50 years! The work really speaks for itself. I am lucky to have been successful and to make work that a lot of people admire. If you want to see how the work has evolved, the show at the Garden is great because it spans about 40 years of my career.

For three seasons, NYBG’s sprawling, immaculately-manicured landscapes will serve as the backdrop for Chihuly’s larger-than-life installations. In addition to the works on view, the Garden will host a roster of tangential programs, from films to evening and weekend events, child-friendly art progams, and more.

CHIHULY will remain on view through October 29, 2017 at NYBG, 2900 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, NY 10458.