"A Quiet Passion" Captures Emily Dickinson's Agony and Ecstasy

Terence Davies’ biopic of the poet Emily Dickinson is one of the British filmmaker’s greatest achievements.

Should we weep or smile with gladness for Emily Dickinson (1830-86)? A Quiet Passion, which depicts the poet’s life from the age of 17 until her death, stints on neither her sufferings nor her private raptures.

In the movie’s most revelatory scene, heartrendingly scored to Thomas Ford’s madrigal “Since First I Saw Your Face,” Cynthia Nixon’s Dickinson summons to her room a slim, elegant “looming man in the night.” His silhouette masks his identity, though the chief candidate is her beautiful young literary admirer, Henry Emmons (Stefan Menaul).

The front door of the Dickinson house having magically opened for him, he glides past a framed profusion of flowers and climbs the stairs. An ecstatic smile on her face, Dickinson awaits him in her darkened room. It scarcely matters that she has imagined the visitor: a metaphysical suitor more potent—and less distracting—than any fleshly equivalent.

Despite Dickinson’s popular image as an agoraphobic, lovelorn spinster whose yarn was slant rhymes—a kind of intellectual Miss Havisham—she knew humor, pleasure, and fulfilment. While disdaining to lift the veil on the Belle of Amherst enigma, Davies has painted a balanced portrait of a woman who, though professionally hamstrung like the Brontës by the literary patriarchy and confined by poor health, meticulously controlled her art and image.

Unlike the wounded fictitious heroines of Davies’ The House of Mirth (2000) and The Deep Blue Sea (2011), Dickinson the child of Puritan New England, played as a heretical Mount Holyoke college student by Emma Bell and from her mid-twenties on by Nixon, does not embody sensuality. She is more severe, unforgiving, and self-abnegating than Chris Guthrie, the intellectually inclined but earth-worshiping daughter of a tyrannical Calvinist farmer in Davies’ 2016 adaptation of Lewis Grassic Gibbons’ novel Sunset Song.

Reclusive from around 1867, Dickinson deliberately—indeed, self-mythifyingly—created a cloister for herself in her family home. That doesn’t mean, however, that she was a shrinking violet or immune to fierce longings: the movie’s title bespeaks more than her vocation. Transfixing here, Nixon plays her as a spiky, even bloody-minded woman, something of a hypocrite when it comes to sexual morality.

Dickinson harbors unrequited love for Charles Wadsworth, a dull Philadelphia clergyman with sideburns and an abstemious wife, and is scolded for her attachment by her devoted sister Vinnie (Jennifer Ehle). Yet Dickinson, who adores her gentle sister-in-law Susan (Jodhi May), tears into her brother Austin (Duncan Duff) after she catches him making love to the opportunistic Mabel Loomis Todd, who became his longtime mistress and, controversially, Dickinson’s posthumous editor.

Wadsworth is a nominee for the mysterious “Master” passionately addressed in three letters Emily drafted between 1856 and 1862. There’s no role in A Quiet Passion for Judge Otis Phillips Lord, the widowed older family friend whom Dickinson may have considered marrying in the late 1870s. The film, judiciously, spares her the possibility of domestic bliss.

She is, undoubtedly, a queen of pain, easily traumatized by losing those she loves. To her friend Vryling Buffam (Catherine Bailey), she predicts she’s unlikely to marry because she could not bear to separate from her family. Though the rebellious young Emily delights in shocking her censorious Aunt Elizabeth (Annette Badland), she is upset at the thought of not seeing her again. The fictitious Vryling, an arch dispenser of Wildean epigrams, marries and moves away.

Eventually, Emily’s sternly Lincolnian but affectionate father Edward (Keith Carradine) dies. So does her inert mother Emily (Joanna Bacon), a character from the Jane Austen school of hypochondriacs. Vinnie aside, all the Dickinsons are prey to a melancholy that seeps into them like damp into walls, partially explaining Emily’s disposition. When Edward forbids the distraught Austin to enlist for the Union army at the start of the Civil War, the entire family deserts the father in the sitting room; the patriarch is crushed.

Following a 360-degree evening shot of the family assembled in the parlor—another of Davies’ achingly beautiful poetic flourishes—the mother, already on the verge of tears, asks Emily to play “one of the old hymn tunes” on the piano. Her rendition of “Abide With Me” triggers the mother’s memory of a doomed youth, presumably an early love, exactly as the singing of “The Lass of Aughrim” recalls for Gretta Conroy the memory of Michael Furey in James Joyce’s The Dead. The awareness of mortality is contagious. Emily catches it, and it becomes her principal subject: “I heard a Fly buzz — when I died.”

If mortal thoughts inspired Dickinson as a poet, her illnesses were allies, too, since they created the conditions for her splendid isolation as an artist. Davies not only shows her living with incurable Bright’s disease—which stabs her kidneys as she writes—but succumbing to the epilepsy that Lyndall Gordon persuasively diagnosed in her 2010 biography. Epilepsy provides the most plausible reason for Dickinson’s self-sequestering, for the genteel society of 19th-century New England would not have tolerated a public seizure.

Enforced or not, Dickinson’s renunciation of an outgoing life drives the claustrophobic second half of the movie, but that renunciation is not simply physiological in origin. She avoids not only courtship but the dissemination of her poetry. The 10 of her 1775 poems that appeared in her lifetime were published anonymously. It’s implied that the cost of editorial interference in her work would have been, like marriage, too great a compromise for her to bear: “Publication is the Auction of the Mind of Man,” she wrote.

Of course, as “Nobody,” which is how Dickinson introduces herself to her newborn nephew Ned in the film, she may have carried self-effacement to a neurotic extreme, flinching from success and fame as a poet. As the daughter of a disengaged mother and an austere father, she may have flinched also from sexual intimacy (a frightening specter). But the resulting hurt she transformed into her terse, often sadistic lyrics—passionately self-lacerating, exquisitely masochistic—is the wellspring of her art, the fuel for her genius.

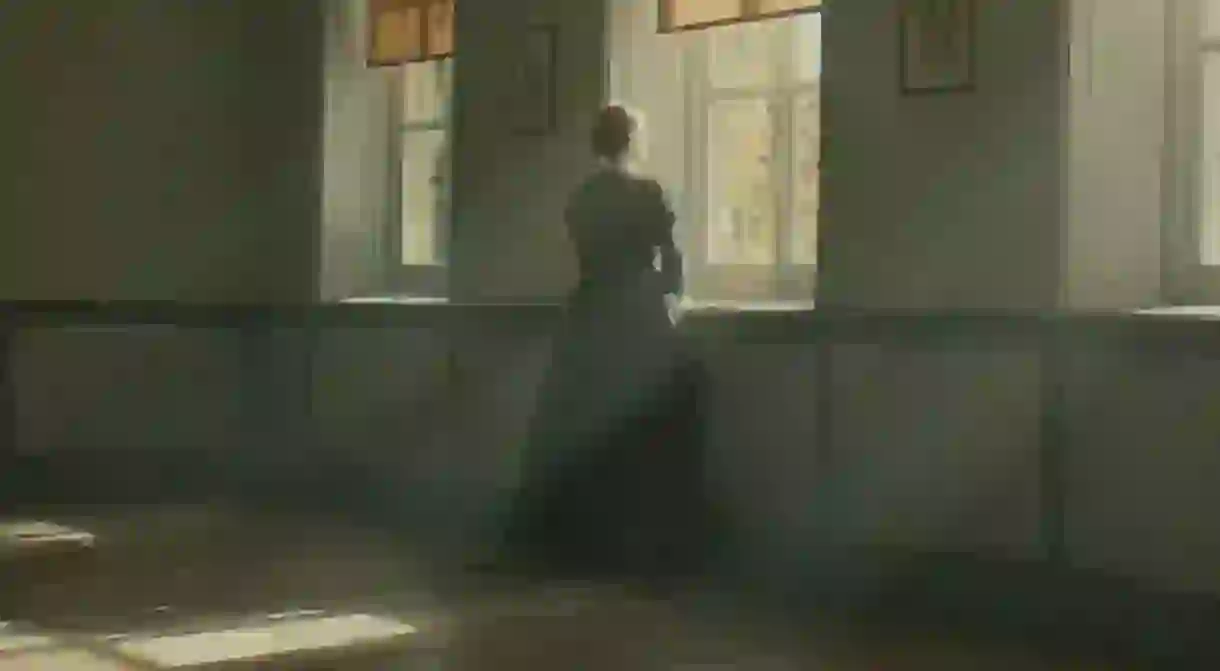

And so is time, the rhythmic flow of which Davies typically lyricizes with slow dolly shots, pans, and static shots. Just before Dickinson conjures her midnight visitor, the camera observes the fading of the sunlight on it, as the camera observed a patch of family carpet in Davies’ 1992 The Long Day Closes. Whereas that masterpiece memorialized moments in the filmmaker’s upbringing, A Quiet Passion memorializes invented moments in Emily Dickinson’s long day’s journey into night and makes them no less indelible.