A City Ablaze: The 19th Century Confederate Plot to Burn New York

On the border of New York state and Canada in November 1864, a conspiracy bent on wreaking havoc and exacting destruction was brewing. A hand-picked concoction of Confederate soldiers, agents, and operatives formed a complex network designed to wage a war of attrition and launch a rebellion of Northern-based sympathizers into action. This is the plot that in the words of one conspirator, John W. Headley, was ‘To create a sensation in New York’, and ‘set fire to the city.’

Though the waning days of the American Civil War were not far in the offing, the nation was still in the midst of massive political and social upheaval. The physical war was far removed from the bustling streets of Manhattan, but the country’s largest city was a raging battleground of ideas. Nearly a year earlier in July of 1863, the city experienced major rioting. Lynch mobs, spearheaded by the Copperheads (Northern Confederacy sympathizers) opposed to draft enlistment of soldiers, touched off a campaign of burning buildings and random violence resulting in the deaths of 118 people. President Abraham Lincoln dispatched Union soldiers from Gettysburg, under the command of General John A. Dix, to take military control of the city until order could be restored.

Robert Martin, a former rebel colonel, was given the charge by Confederacy President Jefferson Davis to organize a subversive espionage and covert operations campaign intent on distracting Union assets and ultimately forcing Lincoln to the bargaining table. Yet some, like Martin’s second-in-command John W. Headley, had retribution on their minds.

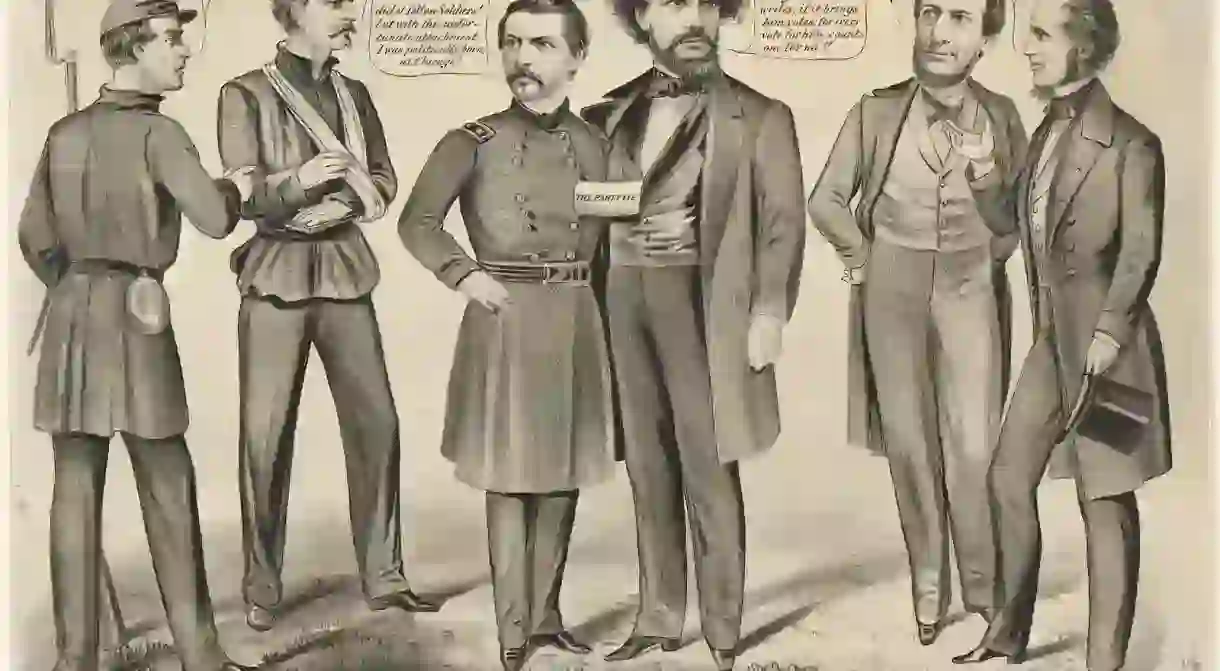

The plot against New York City was as elaborate as its results would be deadly. Originally scheduled for November 15th and due to plague Chicago as well, it was expected to have the support of several democrat politicians such as New York Governor Horatio Seymour, former New York City Mayor Fernando Wood, and Illinois Congressman James C. Robinson. Dozens of fires were planned to be set throughout both major cities. These fires were meant to distract authorities so rebels and Copperheads could seize control of each city’s treasuries and arsenals, while at the same time freeing Confederate prisoners from Fort Lafayette in New York, as well as two Army camps in Illinois – Chase and Douglas.

The landscape of New York City at this time was far from the metropolis it is today. The population was a mere 814,000, most of which occupied the poor tenements of the Lower East Side. Much of what was west of 42nd Street was still dense forest, although plans were already drawn for constructing Central Park. The majority of the commerce in the city took place along the Hudson and East Rivers, while inland the financial mainstay was its hotels on Broadway. These hotels would become the selected targets of the Confederates.

Men like Captain Robert Cobb Kennedy, a hard-nosed former West Point graduate, John W. Headley, and several other operatives planned to check into at least a dozen hotels along Broadway under assumed names and set fire to the bed sheets. They would use bottles of Greek fire – a mixture of sulfur, naphtha, and quicklime – a chemical capable of bursting into flame when exposed to air. Hotels like the St. James, Astor House, the Metropolitan, the Belmont, and Tammany Hall were all on the hit list.

The plot in Chicago quickly fell apart when a captured Confederate operative provided information about the plot in New York City. Secretary of State, William H. Seward sent a telegram to the mayor of New York City, and troops were dispatched to surround Manhattan on land and sea. The troops left on November 15th, so the date of the attack was re-scheduled for the 25th.

144 bottles were distributed among the plotters. The attacks were to commence at 8am at several locations, but one major flaw to the plan became apparent. In an attempt to limit casualties among hotel patrons, after each fire was set the arsonists left their rooms with the doors and windows shut. This deprived the fires of oxygen, thus each one was quickly extinguished; however the attack caused widespread panic.

By the next day, pictures of the conspirators, along with the fake names they used, were on the front page of every city newspaper. Despite a massive manhunt, all the conspirators were able to escape the city by train, though General Dix promised they would all be caught, tried, and executed. The only perpetrator to ever be captured and tried was Kennedy, who was later apprehended during a plot to free several Confederate generals being transported by rail. He was eventually hanged.

There were no reported casualties during the attack. The damage to the dozen hotels that were burned was minimal. Astor House sustained the most damage where the fire did manage to spread to four rooms, so by most accounts the plan was a failure. Although the attack on New York did nothing to change the course of the war, it was well-organized and if it had succeeded, according to the New York Times, it might have been, ‘One of the most fiendish and inhuman acts known to modern times.’