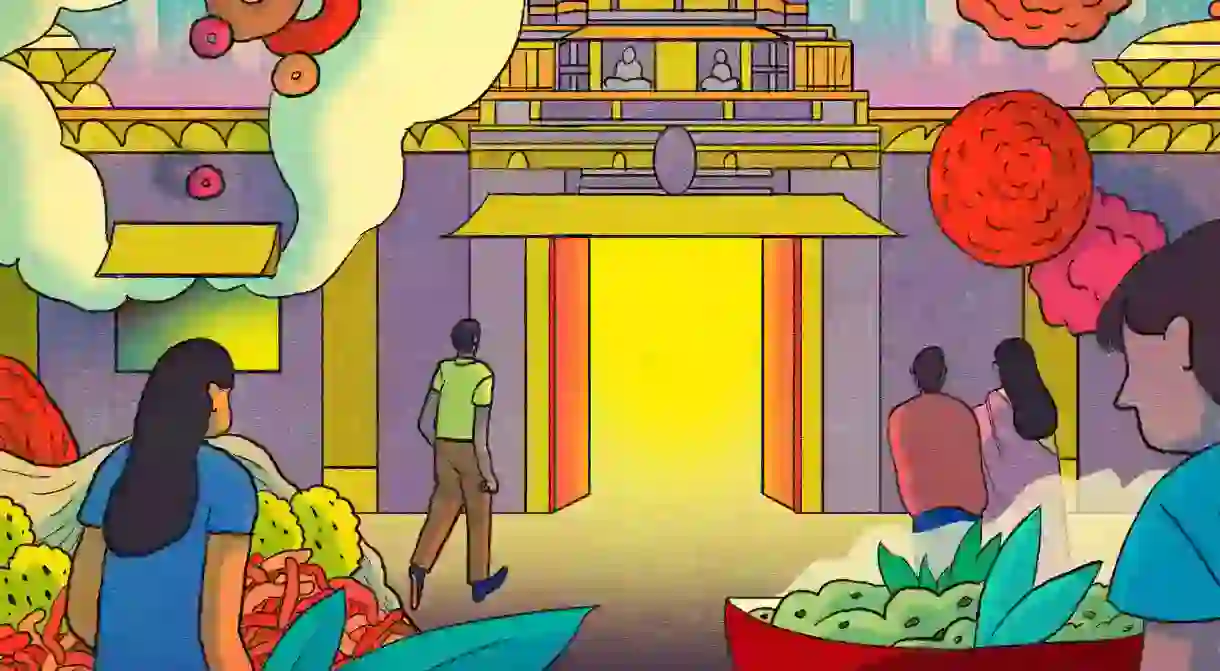

This South Indian Temple in Queens Transforms Food Into a Vehicle of Religious Celebration

The Hindu Temple Society of North America in Queens serves as both a religious and a culinary destination for South Indians.

“Ultimately, we are all seekers of happiness,” says Ramanathan Subramony, a priest at the Hindu Temple Society of North America in Flushing, Queens. “I have a lot of happiness when I’m here.”

Subramony has plenty of reasons to be joyful: arriving from South India just a year ago, he is now heading the first traditional Hindu temple of its kind in the United States, smack-dab in the middle of a neighborhood that over 200,000 people of Indian descent call home.

Often referred to as Temple Ganesh in reference to its presiding deity, Lord Ganesh (the god of wisdom and “remover of obstacles”), the destination welcomes around 150 worshippers each day, a number that quickly swells to 500 during weekends. These devotees revel in the aura of the space; boasting an aesthetic reminiscent, albeit on a smaller scale, of the grandeur of the temples that pepper all of India, Temple Ganesh is cozied up in a corner of New York City that quickly transports passers-by to another world.

A non-profit endeavor, The Hindu Temple Society of North America first opened its doors in 1970. “It was not as big as it is now,” explains Subramony while sitting in his office, snugly set in a corner of the structure that houses the temple and a few other offices. When examined from the outside, the temple makes quite the impression. Large columns and gold and red statues mark the entrance, which features a “please remove your shoes here” sign right in front of a massive brown door and a small fountain to wash hands. Since its inception, the facility has undergone five consecrations – religious rituals conducted when the temple is expanded or a piece of the building is updated and changed. The next consecration is slated to occur in 2020.

As the history of immigration and a New York culinary scene dominated by foreigners have taught us, food plays an essential role in shaping a neighborhood, especially one functioning as a transplanted home to a fairly large community. Since 1993, members have made it a point to turn their house of worship into a home by opening a canteen – called Temple Canteen – in the temple that today serves a dual function: The canteen’s kitchen dreams up the coveted foods of their home country while adhering to the dietary restrictions required by the Hindu religion.

But Temple Canteen also functions as a community destination, embracing diners of all kinds, whether it’s Hindus looking to indulge in a religiously sanctioned meal or seculars craving South Indian specialties. Temple Canteen is home to a confluence of cultures – both from the US and abroad – united by their love for South Indian food.

“The purpose of [the canteen] was to make holy offerings for the deities,” explains the priest. As per Hindu tradition, the ritual, called Naivedhya (a Sanskrit word translating to “offering to god”), is performed three times a day.

According to Hinduism, a devotee’s behavior and disposition towards others are directly related to his or her eating habits – a notion that renders Temple Canteen’s services necessary for successful religious practices.

“Whatever you take inside, it constitutes your behavior. That’s what we believe,” says Subramony. “Food can influence the way in which you behave, so if you [indulge in prohibited fare] like meat and fish, demonic sensations will come to mind. That’s why you have to be very selective when you’re having your food.”

The way the permissible food is cooked also influences an eater’s behavior. “The thoughts that are getting into the mind of the person who prepares the food will have an impact on it, and consequently it will be affecting us also,” says the priest. “That is why we have these food restrictions.”

Strict laws dictate the way Naivedhya is carried out: the offerings may include flowers and certain foods, but they must be prepared in specific ways. Religious cooks prep the fare in the canteen and then take it to the temple, where 10 priests bless the offerings and distribute them among the devotees. At this point, the Naivedhya (food offered to the deity) turns into the Prasad (food received from the deity). The food is offered to worshippers free of charge.

“It’s not a profit-making business,” the priest says of the on-site eatery.

The blessed food is strictly vegetarian, so worshippers revel in dosas (a favorite, according to Subramony), idlis (savory rice cakes) and vadas (fried snacks that can be made with a variety of ingredients, including legumes and potatoes) among others.

“The idea is that, when the devotees come from long distances and when they are tired, there is no need for them to go out searching for food,” says Subramony about those flocking to worship from all over New York, New Jersey and Connecticut.

Although there are several South Indian restaurants in the area, here worshippers consume a meal in a peaceful temple surrounded by the people and the fare that remind them of a far-away home, while obeying religious customs and laws – a fact that Subramony is quick to underline. The goal of Hinduism, explains the priest, is to reach the “brahmam”: what is considered to be the ultimate reality. The food one eats is thought to be intrinsically connected to one’s potential to achieve that “ultimate truth.”

“Anything that you see here is a reflection or a part of the brahmam,” says Subramony. “You do not need to seek a god externally, sitting in a heaven or a hell. The god is within yourself [and can be reached] by practicing these traditions. The goal is to elevate yourself to a position where you get unified with the brahmam.”

Ultimately, Hinduism preaches the importance of peaceful coexistence, an idea that dates back centuries but has only recently caught on in Western civilization. The Zen movement has spread across an American society that is plagued by the antithesis of peace, both politically and socially. But despite this unrest, Subramony feels lucky not to detect any hints of intolerance when he steps out of the safe confines of Temple Ganesh.

“I heard that in the earlier days we had a lot of issues,” he says, bringing up incidents involving rotten tomatoes and eggs thrown on the site’s facade. “But these are gone. Now, you have the freedom of choice to practice whatever religion you want. I don’t feel any kind of intolerance here.”