A Human Rights History Guide to NYC’s Greenwich Village

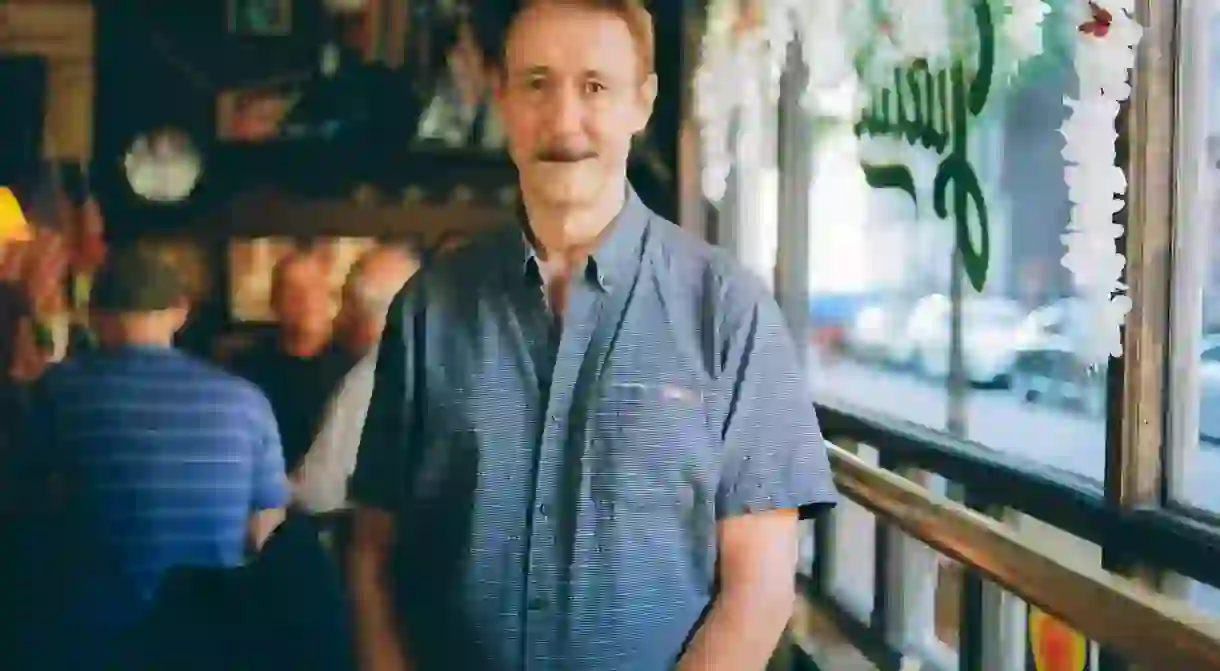

Jay Shockley, co-founder of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project, shares the Greenwich Village landmarks where cultural turning points occurred.

The Culture of Pride celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

It’s not unusual to see large groups of women making a swift selfie stop outside of The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street before piling back into their Uber. “That’s sort of an odd phenomenon,” says Jay Shockley, a resident of Greenwich Village since 1978 and co-founder of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project, an initiative that maps the cultural sites associated with the LGBTQ community across New York’s five boroughs.

“The point of our project is to make a link between physical places and the memory and history that happened there,” he explains. “What’s incredibly heart-warming is we’ve encountered countless European couples with little tiny children who have purposely taken them to Stonewall as part of their touring around New York, so that’s been a really pleasant surprise.”

The Stonewall Inn is, of course, a good starting point for a tour of New York’s human rights landmarks. It was here on June 28 1969 that the continued harassment of the LGBTQ community by the NYPD erupted in violent protests, which helped birth the Pride movement. But Shockley’s research reveals examples of organized, effective gay rights activism that preceded the famous Stonewall uprising.

In 1966, a man named Dick Leitsch, leader of the Mattachine Society (the first gay rights group in America), staged a “sip-in” at Julius’ bar at 159 West 10th Street. He enlisted a Village Voice photographer to capture the moment an openly gay man was refused service at a New York drinking establishment, a common occurrence due to a policy of the State Liquor Authority that revoked the license of any bar knowingly serving gay men or lesbians.

“We now believe that this was the first gay civil rights action in the United States that was planned and had an actual effect at the end of it,” says Shockley. This was three years before the events at Stonewall.

Right outside of The Stonewall Inn is Christopher Park, home to the Gay Liberation sculpture, a monument depicting two same-sex couples in white-painted bronze, created by artist George Segal in 1980.

“A lot of early gay rights leaders didn’t like it for the following reasons: it was done by a straight sculptor, and it’s two couples that are both white,” Shockley explains. Following red tape and numerous homophobic complaints, the artwork was finally installed in 1992 – 12 years after it was commissioned.

At the northern end of the park, you’ll find the Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth flagpole, which was erected in 1936 in memory of the first officer killed during the Civil War. Ellsworth, who was the leader of the first American Zouave unit (and had a close, possibly romantic relationship with Abraham Lincoln), was shot and killed after removing a Confederate flag from the roof of a hotel in Alexandria, Virginia. When he heard the news, Lincoln is said to have remarked through tears: “I will make no apology, gentlemen, for my weakness, but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in great regard.”

A stone’s throw from Christopher Park is another pretty community garden with a significant past. In the 19th century, a women’s prison was built on the site where the Jefferson Market Garden now resides. It was opened by the Women’s Prison Association as a means of addressing the issues facing female inmates, who at that time were incarcerated with men and had little opportunity for rehabilitation after release.

“Most women who were in prison in the 19th century were in there because they were poor,” says Shockley, “or because they had fallen into prostitution, because their husbands had died or they had no other means of financial support. It’s just astounding to read all the steps women had to go through [behind bars with men].”

Continue to Sheridan Square (which is actually a triangle at the intersection of West Fourth Street, Washington Place and Barrow Street) and you’ll arrive at the site of Café Society. Barney Josephson opened the basement jazz club in 1938, selecting its Greenwich Village location specifically to attract the neighborhood’s liberal, progressive crowd. It was the first racially integrated nightclub in New York City, and diverse audiences gathered to watch lauded musicians of the day, including Duke Ellington, Bessie Smith, Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday, who first performed her civil rights protest song ‘Strange Fruit’ here.

Historically, Christopher Street and the surrounding area was full of gay-owned, activism-driven businesses. Case in point: the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop (once located at 291 Mercer Street), which was the first store in America dedicated to gay and lesbian literature. Established in 1967 by Craig Rodwell, it was billed as “A Bookshop of the Homophile Movement” and a meeting place for LGBTQ activists to build community and plot protests.

Shockley has seen Greenwich Village change significantly over the decades, with leather shops and dive bars giving way to upscale restaurants and designer boutiques. Still, you can’t go anywhere in the Village without brushing up against history, and his goal is to shed light on the stories and individuals who paved the way for human rights progress, both in the city and beyond its borders.

“You look at whatever minority community there is – if their stories aren’t being told, they’re not being recognized,” says Shockley. “We realized early on that people are not talking about the contributions we as a community have made to American culture. Our project is documenting aspects of why and how we’ve made a disproportionate impact on the culture of New York – the center of theater, fashion, you name it. There’s an awful lot to document.”

Pride 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in New York City and the beginnings of the international Pride movement. To celebrate, Culture Trip spotlights LGBTQ pioneers changing the landscape of love around the world. Welcome to The Culture of Pride.