5 Things You Didn’t Know Were Invented in South Jersey

You may not imagine South Jersey as a hotbed of innovation, but students at the multiple universities and nationally ranked high schools here would disagree. And so would the genius minds behind these inventions—some of which you use every day—that were developed in South Jersey.

Teflon™

Chemist Roy Plunkett was experimenting with Freon (the refrigerant gas) at DuPont’s Jackson Lab in Deepwater in 1938 when he stumbled on something downright futuristic. After filling cylinders with the gas, he tried to discharge them. One didn’t go off, and fearing an explosion, he cut it open. Inside was a waxy, white substance that Plunkett decided to test. He’d accidentally created a slippery, heat-resistant polymer. It was first used several years later by scientists working on the Manhattan Project, but in the early ’60s, DuPont had the brilliant idea to coat some cookware. Today, most of us wouldn’t dream of frying an egg or baking a cupcake without the help of this South Jersey invention.

Electron Microscope

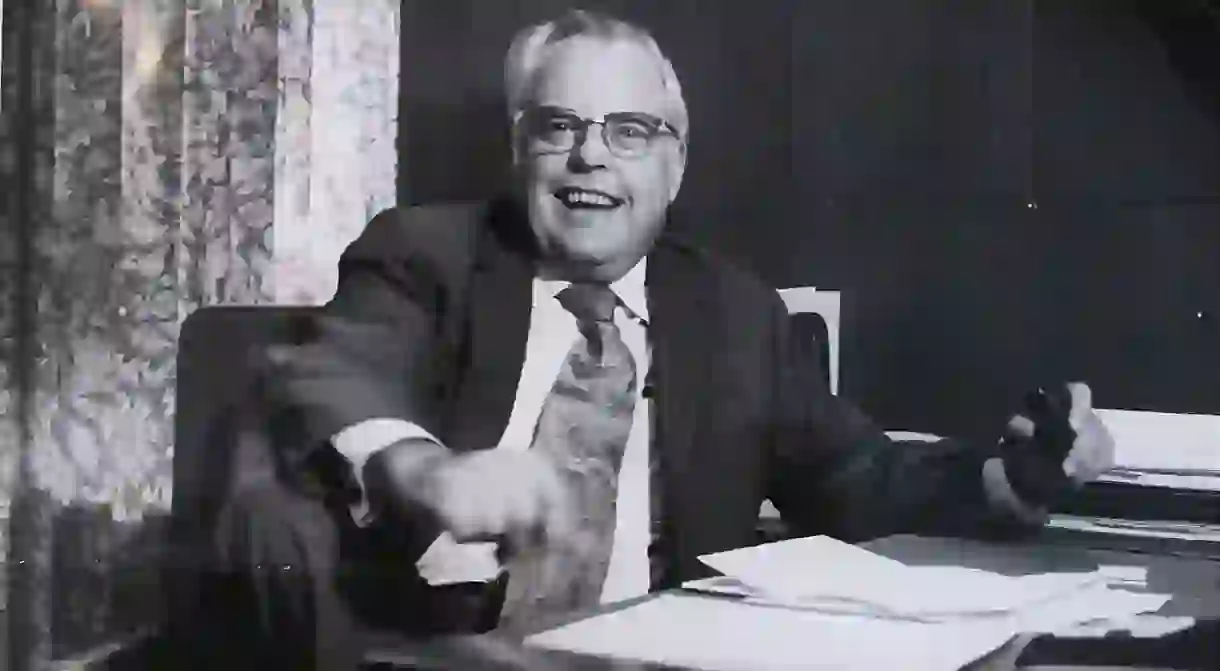

Ok, so this one wasn’t technically invented in South Jersey, but it was perfected here. James Hillier, then a graduate student at the University of Toronto, created a prototype of the electron microscope in 1938. It magnified an image up to 7,000 times, but all that concentrated magnification also tended to burn things—“to a crisp,” as Hillier put it. After grad school, Hillier went to work at RCA in Camden, where he was able to perfect the device. Today, scientists routinely use Hillier’s invention to peer at individual atoms, something Hillier might’ve thought was impossible in 1938.

Condensed Soup

Ready to have your mind blown? Campbell’s Soup existed long before the ubiquitous can that it comes in today. In 1897, chemist John T. Dorrance joined his uncle’s business, Joseph Campbell & Company, which made soup, but only for Camden locals; it cost a fortune to ship heavy loads of cans to stores. Dorrance came up with a method for condensing the soup, reducing the weight and making the project much cheaper to package, store, and ship.

Band-Aids

Josephine Dickson was a clumsy cook, and her husband Earle was a friendly guy. Earle Dickson, a cotton buyer for Johnson & Johnson in New Brunswick, was constantly helping his wife bandage her nicked fingers with gauze and bulky tape. He eventually designed an easier way, attaching a small piece of gauze to a sticky piece of surgical tape. In 1920, he sold the idea to his bosses at Johnson & Johnson, but the public didn’t get onboard until a few years later when Band-Aids were distributed free to Boy Scouts. After that, the idea stuck.

Barcodes & Scanners

There are barcodes on everything. After all, they’re how we identify goods and how we make purchases. But checkout lines might look a whole lot different if it weren’t for Atlantic City’s N. Joseph Woodland. In 1952, he invented what he called a “classifying apparatus and method.” It was a series of concentric circles that could represent encoded data. Eventually, those circles became the barcodes we know today. A few years later, C. Harry Knowles came up with a prototype for the world’s first laser barcode scanner at Metrologic Instruments in Blackwood.