The Untold Story Behind Diego Rivera’s Murals in Detroit

During the 1920s, backed by the wealth of the booming auto industry, the DIA’s collection had been growing in both strength and size under the stewardship of German art scholar Wilhelm Valentiner, who was also revolutionizing what a modern art museum could be.

Despite the crash of 1929 devastating the city, Valentiner’s ambition culminated in 1932 with a project to have an original series of frescoes related to the history of Detroit created in the central grand marble court of the museum. With the financial backing of Edsel Ford, who, along with his wife Eleanor, was a great benefactor of the museum, Valentiner appointed the most prominent member of the Mexican muralist movement at the time, Diego Rivera.

Rivera had recently been celebrated by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and had just completed a mural at the San Francisco Art Institute and accepted the challenge. He was fascinated and amazed by the advanced technology present in Detroit’s auto industry at the time, spending months studying and taking inspiration from the Ford River Rouge Complex in particular.

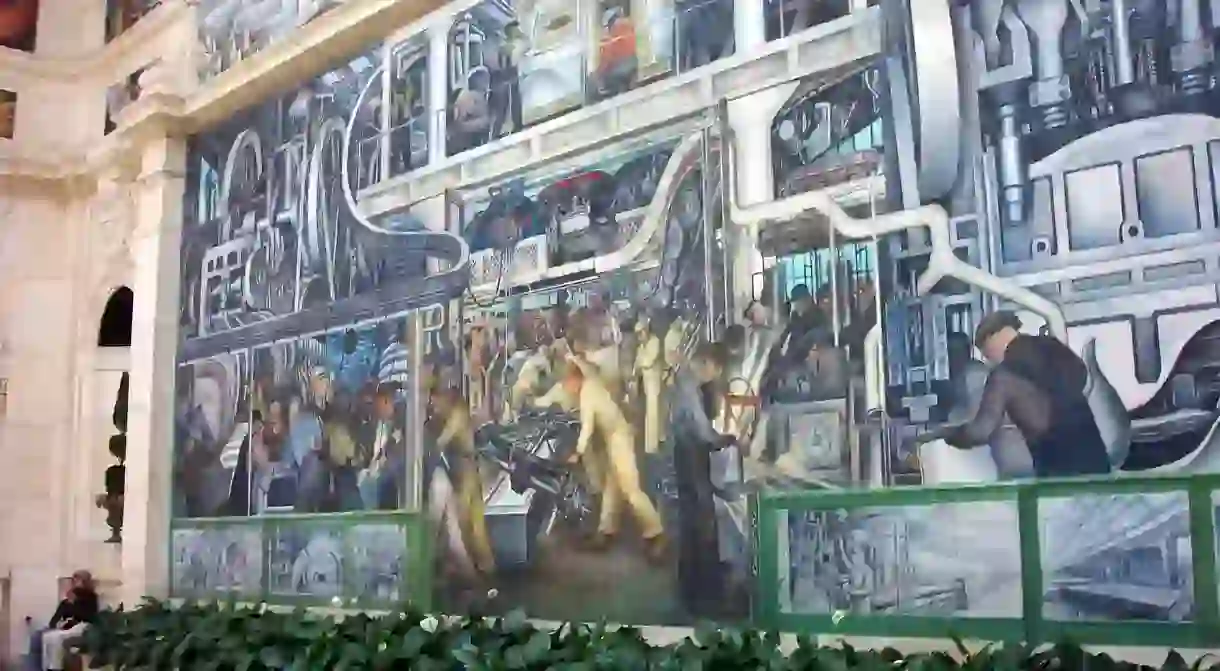

After creating hundreds of sketches and concepts, he was ready to begin the 27 frescoes that would cover all four walls of the court and make up Detroit Industry. Among them, the relationship between technology, science, and man was depicted, largely set within a factory of laborers. He and his assistants undertook a relentless schedule, regularly working exhausting shifts without any breaks. The work took only eight months, being completed in early 1933.

Rivera thought it was his most successful work, but for many reasons, it proved controversial. Rivera’s politics meant the content was viewed as dangerous Marxist propaganda and “un-American,” while others were shocked and offended by workers of different races working side by side and by “vulgar” and “pornographic” nudes. A modern homage to the nativity scene was also described as blasphemous.

The controversy, which has since been suggested was stoked or even invented by Ford, proved useful, driving public interest and guaranteeing the project’s success. Calls for the murals to be destroyed were soon forgotten, and the work has gone on to become iconic as the undisputed jewel in the crown of the DIA.