Detroit’s Decisive Role in the Underground Railroad

During the late 18th and early to mid-19th century, a network of people, secret routes, and safe houses existed in the U.S. to enable African-American slaves to escape to the north. Once laws were passed requiring free states like Michigan to report and assist in the capturing of fugitives, Detroit’s position as a gateway to Canada increased its importance in the network, earning it the nickname the “Doorway to Freedom.”

For as long as there was slavery in the U.S., there were also escape routes, with Mexico, Spanish Florida, and British North America (present-day Canada) all possible destinations for those able to flee. However, once Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, heading north became the best option for freedom, which meant taking what became known as the Underground Railroad.

The Railroad was organized by free African Americans, a number of religious communities, and abolitionist sympathizers, who assisted slaves along a route of secret meeting points, providing food and shelter and transportation or guidance to the next safe destination. Though not literally an underground railroad, the network used rail terminology, including calling meeting points “stations,” those assisting slaves “conductors,” and slaves “cargo.” When the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, fugitives pursued and captured in free states were to be sent back to the South, which made it even more crucial for them to leave the U.S. entirely. Though exact numbers remain impossible to know, it is estimated that between 30,000 and 100,000 people made it to Canada via the Railroad.

Detroit became an important part of the Railroad because of both its location and its defiant community. Separated from Canada only by the mile-wide Detroit River, it was given the code name “Midnight” to symbolize its position as the end of the line. It also had both a large black population and a large number of abolitionists who, despite the Act of 1850 making it illegal to assist those fleeing slavery, played an active role.

George DeBaptiste, born a free man in Virginia, was a prominent Detroit conductor, using his steamship the T. Whitney to transport hundreds of slaves to Ontario. He was also a member of several prominent anti-slavery groups and the Second Baptist Church of Detroit, which harbored around 5,000 slaves over 30 years as the “Croghan Street Station.” The First Congregational Church of Detroit was another vital station in the city, and Seymour Finney was another noted conductor, sheltering many runaways in his downtown hotel and stables.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Beu8_NdH0iD/?taken-at=38938540

Outside of the city, Dr. Nathan Thomas was an important conductor in western Michigan, who helped between 1,000 and 1,500 slaves make their way to Detroit and subsequent freedom over a 20-year period. Elizabeth Chandler was another great figure; she established the Logan Female Anti-Slavery Society in Lenawee County, another key station about 60 miles (96.5 kilometers) southwest of Detroit.

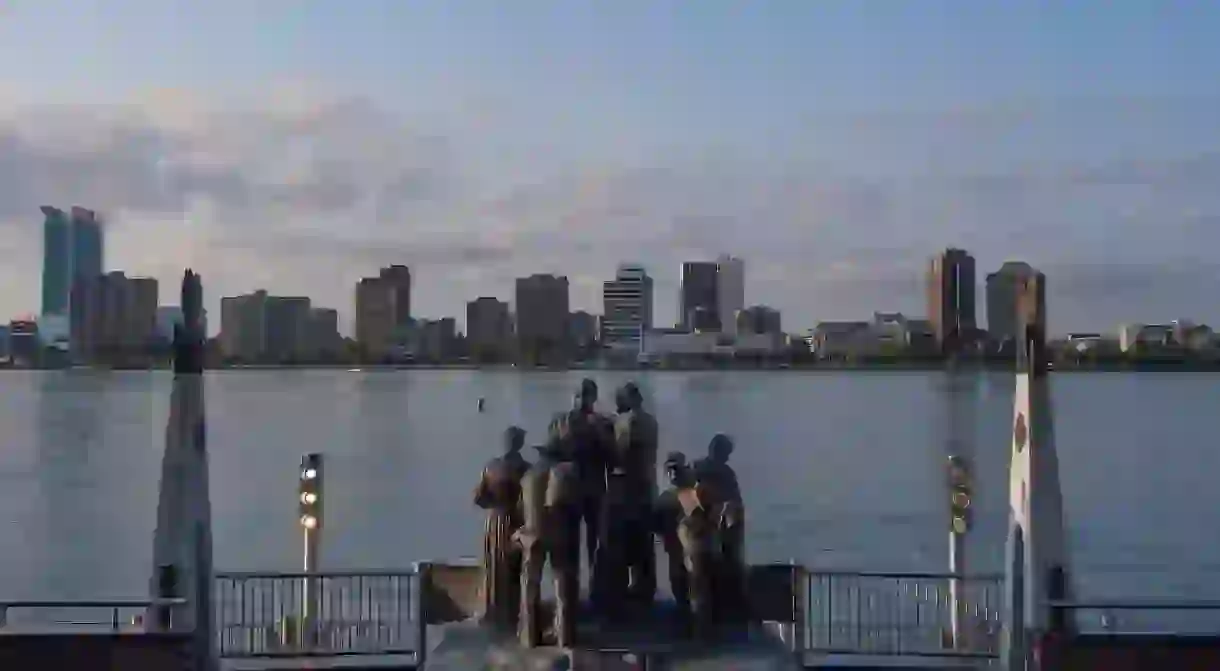

Underground Railroad sites to visit in Detroit today include the “Gateway to Freedom” Memorial in Hart Plaza, tours of the Second Baptist Church and First Congregational Church of Detroit stations, and exhibitions at the Detroit Historical Museum and Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History.