The 100,000 Little Free Libraries Currently Found Across 108 Different Countries

Last year, Sharalee Armitage Howard was told that the 110-year-old cottonwood tree in her front yard was dying and needed to be removed. The librarian, bookbinder and artist had an idea: why not turn it into a library? And so she did.

The tree in Sharalee’s yard became Little Free Library number 82,068, which – complete with a large green door peppered by miniature wooden books such as Call of the Wild and Nancy Drew – has come to, at least partially, define the town it calls home: Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

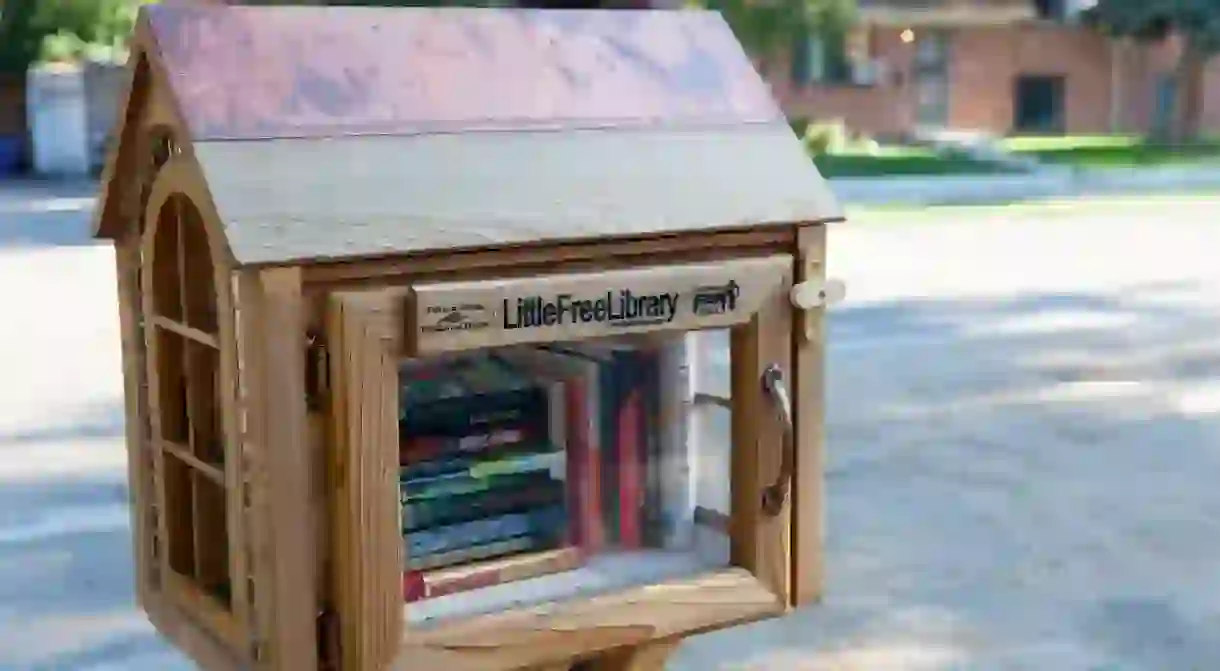

Today, there are a hundred thousand registered Little Free Libraries across 108 different countries. Although not all are as majestic as Howard’s creation, the objects all have the same goal: to encourage literacy while fostering a sense of community in all types of neighborhoods.

The first library was set up in 2009 by one Todd Bol of Hudson, Wisconsin, in honor of his mother, a schoolteacher. Bol simply built a tiny model of a schoolhouse, filled it with books and installed it in his front yard. Rick Brooks, who at the time worked at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, noticed the set-up and approached Bol about turning it into a larger project. In 2012, the Little Free Library non-profit organization was established. Bol passed away in 2018 and Brooks is now retired, but he is still in touch with the 12 staff members who work to keep the non-profit going.

Building your own library

Just about anyone, anywhere, can start a Little Free Library. There are two ways to do it: build one yourself, or purchase one from the organization directly. In the latter case, stewards – as the librarians are called – get to choose from over 30 designs that vary in style and range in price from $150 to $500, and are all handmade by Amish craftspeople in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Financially speaking, these sales help keep the non-profit afloat, alongside various donations. Upon registration, stewards receive an official plaque to install on their library, which in turn gets added to the online map showcasing all the locations set up across the globe.

Once the library is up and running, anyone is free to take out a book and, although all are encouraged to add a different title to the collection, it is not a requirement. “If you don’t have a book to share, that’s OK,” says Margret Aldrich, the non-profit’s director of communications. “You can still take one home.”

The caretakers of Little Free Library

Although, in general, kids’ books are the first ones to go, Aldrich is avid about noting the vast variety of tomes that claim spots in the various bookcases, a fact that highlights the nuances of each community. “It becomes a mix of everything, from popular novels to cookbooks to non-fiction,” she explains. “Every Little Free Library is different and really starts to reflect the needs of the neighborhood and its personality.”

Those personalities and characters are reflected in the stories behind each library. For example, Malaz Khojali launched an entire network of libraries across Sudan in an effort to “get books into the hands of local children.” As of today, she has started over 60 different libraries. Her goal is to surpass 100. In Ocean Hill, Brooklyn, meanwhile, Julien Zeitouni installed a bookcase through the organization’s Impact Library Program, which provides no-cost libraries to communities where books are scarce.

One thing resonates across all tales: a love of reading may be universal, but access to reading materials isn’t and Little Free Library is trying to bridge that gap. Given the number of libraries now unleashed throughout the world and the dedication needed to keep them full of books, the stewards have become more than purveyors of literacy. “They really are the caretakers of Little Free Library,” says Aldrich. “They keep it tidy, keep an eye on things. Lots of stewards will do extra things like celebrate different holidays at their library, host a story time for kids in the neighborhood. They get creative.”

Reaching new heights

In recent years, as the project’s popularity reached new heights – Aldrich thanks the power of social media for that – the organization noticed an increased demand for libraries on public property. From hospital waiting rooms to public parks and laundromats, folks have set up the book exchange in different parts of their neighborhoods, if granted permission from the city. For example, the Smithsonian recently installed a book box at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC to honor the Native American culture spotlighted within the walls of the museum.

One thing that all stewards have to deal with is thievery. “It has happened, but it is quite rare,” says Aldrich. “When something bad does happen, it can feel very personal and really disheartening.” The communications director is quick to point out that episodes of vandalism, although unfortunate, have undoubtedly led to a strong bond between community members. “They rally around the steward,” she says. “It’s wonderful to see that when there’s something negative, positives can come up as well.” That, after all, sounds just like the moral of any good book.