A Tour of Frank Lloyd Wright's Chicago

It was in Chicago that the USA’s most famous architect, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), cut his teeth, establishing his unique turn-of-the-century Prairie style. Discover the legacy he left behind by touring these remarkable landmarks.

After the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, thousands of people were drawn to the city. Some came to help rebuild, while others were lured by the prospect of new business opportunities. Some 16 years after the fire, the population was booming and new developments were cropping up everywhere, capturing the imagination of 20-year-old student Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright dropped everything to move to Chicago, where he would spend the first 20 of his 70-year career.

In Chicago, Wright worked on numerous projects under the instruction of architecture greats Joseph Silsbee, Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan (creators of masterpieces such as the Unity Chapel, the Auditorium Building and the Wainwright Building, respectively) before establishing his own practice. The turn of the century was for him an era of transition, and the Windy City became a playground where he experimented with the concept of the modern American home. His Prairie-style houses – the most notable of which can be found in Oak Park – were designed to resemble the flat prairie landscape of the Midwest, combining strong horizontal lines, flat or hipped roofs with overhanging eaves and long bands of windows. Inside, built-in cabinetry, high-quality craft, natural materials and pared-back decoration were key.

Beyond residential buildings, Wright also designed notable public works such as Unity Temple and The Rookery. Wright designed more than 1,000 structures during his career, over half of which were completed. While many of these still stand, the following buildings are prime examples of Wright’s vision and his ‘organic architecture’ philosophy, which aimed to create harmony between humanity and its environment. Of his appreciation for the natural world, he said, “Nature is my manifestation of God. I go to nature every day for inspiration in the day’s work.”

Wright’s own home and studio

One of Wright’s first projects in Chicago was his own home. With a $5,000 loan from his employer Louis Sullivan, Wright bought a lot on the corner of Chicago and Forest Avenues in suburban Oak Park in 1889, where he built a Shingle-style property for himself and his new bride Catherine Tobin. He remodeled the house several times (most notably adding a studio in 1898), using it as a site of experimentation that would heavily influence his work to come – especially the development of his Prairie School architecture. Despite its modest size, the interior is an early indicator of Wright’s preference for breezy open-plan spaces. The home, with its dark brick and accent shingle cladding, is situated in what is now known as the Frank Lloyd Wright Prairie School of Architecture Historic District in Oak Park, along with 27 other structures designed by Wright. Visitors can take a guided tour of the house and studio or a walking tour of the neighbourhood.

Unity Temple

Considered the greatest public building of the architect’s Chicago years, Unity Temple in Oak Park was also one of Wright’s most revolutionary. Wright himself dubbed it his “contribution to modern architecture,” as the striking monolithic cube broke with almost every convention of traditional Western ecclesiastical architecture, most shockingly in its use of raw, exposed concrete. Church funds for the project totaled a modest $45,000, so Wright picked the unorthodox material for its cheapness as well as its honesty and simplicity. Wright came from a family of Universalists – his father was a preacher – so he identified with the faith’s principles of unity, truth, beauty and reason. His design reflects these ideologies, particularly the sanctuary: light streams in through a grid of amber-stained glass ceiling lights, while warm colors provide a contrast to the building’s austere grey exterior. The interior is free of overtly religious iconography, allowing the harmonious geometry of the space to speak for itself, while the seating is designed so that no one would be more than 40 feet (12 meters) from the pulpit. The building underwent extensive renovation work (totaling $25 million) in 2015 and reopened in 2017, with public tours available through the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust.

The Rookery’s Light Court

When Wright took an office in The Rookery, built in 1886, the 11-story building was one of the tallest in the world and a beacon of modern civic architecture. At its heart was the Light Court, which the original architects John Root and Daniel Burnham designed to be the building’s jewel in the crown, providing light to all of the interior offices. It was this part of The Rookery that Wright was invited to renovate in 1905 by the building’s manager, Edward C Waller. It was a huge undertaking for the budding architect, as the lobby was considered the most lavish in all of Chicago, but Wright wasn’t afraid to strip back Root’s elaborate ironwork, replacing much of it with white marble with gilded Persian-inspired ornamentation. While Wright stayed true to his Prairie style, with clean lines, harmonious symmetry and simple lighting, the interior was nonetheless one of the most luxurious of his career. It was also the only project Wright completed in downtown Chicago. Today, the building is one of the most recognized landmarks in Chicago’s financial district. It contains mostly private offices, but tours can be arranged through the Trust.

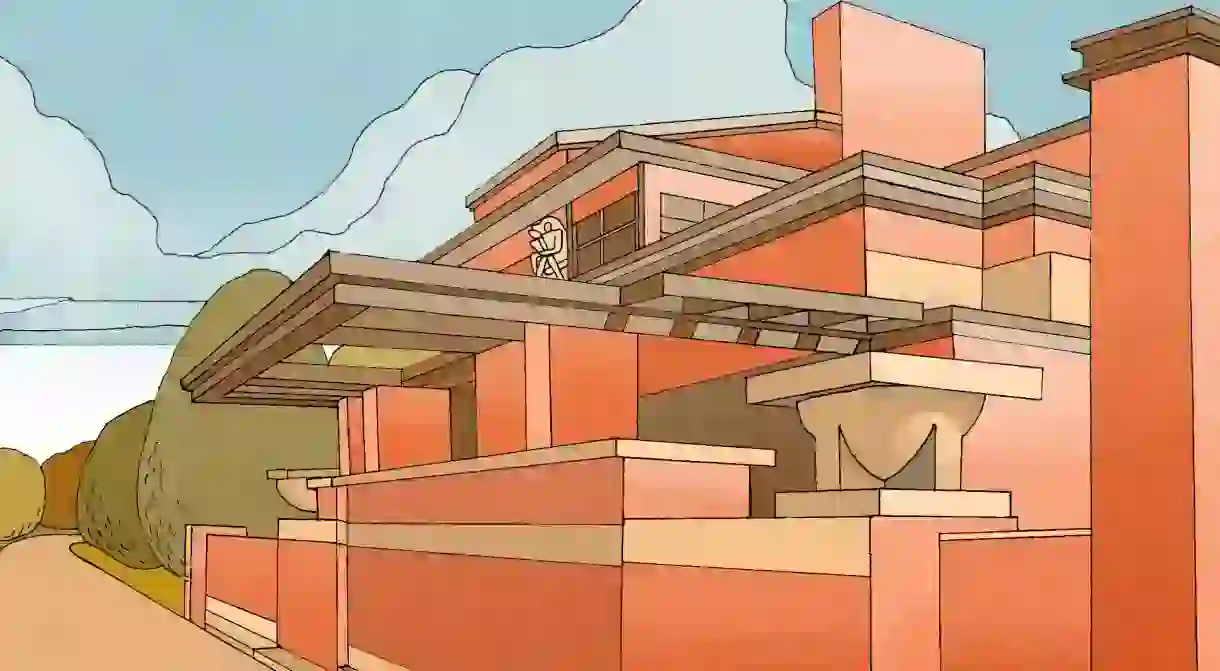

Robie House

Nestled in the University of Chicago campus in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood, the Frederick C Robie House is widely considered to be the greatest example of Prairie School style in the country. Unrelentingly horizontal, it’s Wright’s most progressive Prairie house, with dramatic cantilevered roof eaves and low-slung walls wrapping around the house to create long terraces and balconies, complete with huge bands of glazing.

“The house is conceived as an integral whole – site and structure, interior and exterior, furniture, ornament and architecture, each element is connected,” says the Trust. The master of open-plan living, Wright created an expansive and breathtakingly simple living space that is considered one of the great masterpieces of the era, while the house itself was recognized as one of the top 10 most significant structures of the 20th century by the American Institute of Architects in 1991. The structure was almost torn down in 1957, but Wright led a successful campaign to save it. The building is currently owned by the University of Chicago and offers interior tours when the school is not using parts of the building.

Emil Bach House

Situated one block from Lake Michigan in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood, the Emil Bach House represents the later phase of Wright’s Prairie style. In comparison to Wright’s expansive open-plan suburban designs, this home was relatively compact, designed as one of a series of modestly sized cubic homes in the city. It is the last of its kind in Chicago and was intended as a summer home when it was built, with a sprawling garden and stunning views of the lake. The home features a Japanese tea house and gardens, indicative of the turn Wright would take towards a Japanese aesthetic shortly after the completion of the Bach House in 1915. The house is no longer considered a country home, but is instead a hidden gem tucked in between several high-rise condominium buildings. Guided tours of the property run from May to September, but the real highlight is that the home is also available for holiday rentals and private events.