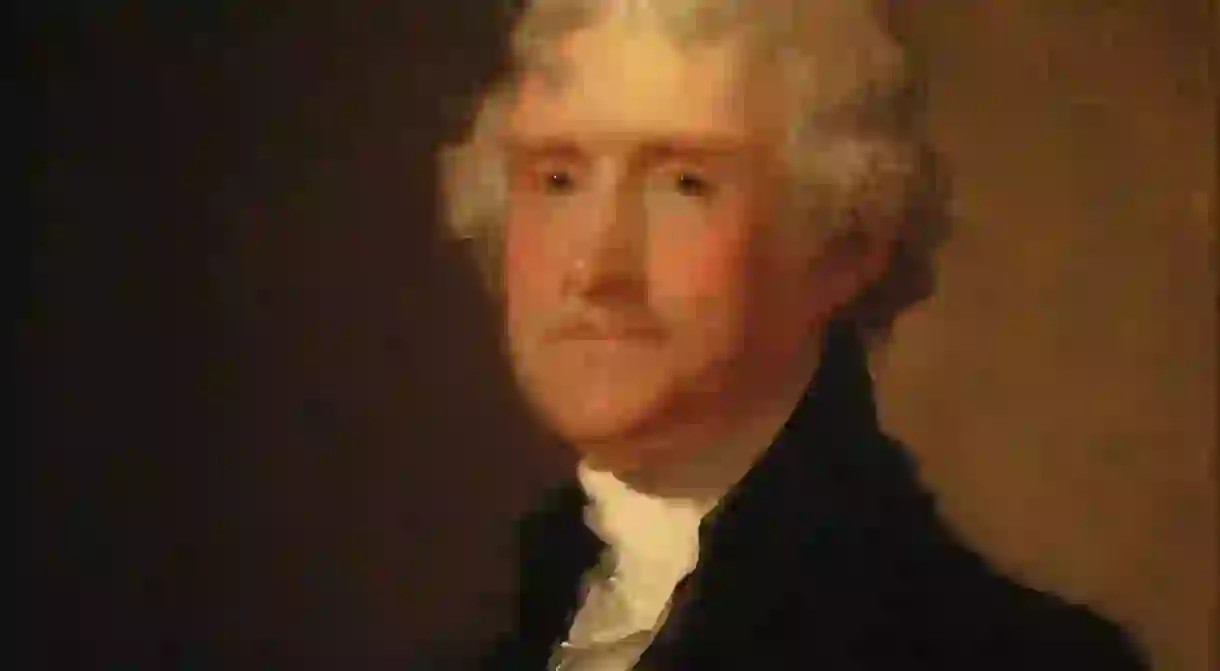

The Story Behind John Adams and Thomas Jefferson’s Awkward Fallout

If John Adams and Thomas Jefferson are discussed in the same breath, it is usually about their twin roles as American founding fathers. But a lesser-known rivalry followed their decades of friendship.

Although the New Englander Adams and the Virginian Jefferson were different in many ways, the two developed a strong relationship based on mutual respect at the 1775 Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

They were both intimately involved in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence and traveled to France together in 1784 on diplomatic missions (although Adams was officially posted a short boat ride across the channel in England).

While in Europe, the two even visited Shakespeare’s home and chipped off a piece of his chair as a souvenir, which Adams justified as being “according to the custom.”

So deep was their affection for each other that Jefferson wrote of Adams to James Madison, “I pronounce you will love him if you ever become acquainted with him,” and Adams told Jefferson that “intimate Correspondence with you… is one of the most agreeable Events in my Life.”

But for two such politically significant and passionate men, it is unsurprising that it was politics that finally drew them apart. Adams was the second president of the United States. When Jefferson succeeded Adams as president in 1800, it was the first peaceful transition of power from one political party to another in western history.

But Adams, who disagreed with many policies that he knew Jefferson would pursue as president, left a not-so-friendly parting gift: a raft of last-minute political appointments of officials who would work to undermine Jefferson’s policies. Jefferson wrote that he had been “brooding over it for some little time,” and the two men stopped speaking over it for years.

It wasn’t until after Jefferson vacated the presidency in 1809 that a reconciliation was initiated. A friend of the two men, Dr. Benjamin Rush, felt it would be possible to repair the friendship and unsuccessfully tried for two years to persuade the men to write to one another.

The tipping point came in 1811 when one of Jefferson’s neighbors was visiting Adams in Massachusetts and came back with a bit of overheard information: he had heard Adams say, “I always loved Jefferson, and still love him.”

“This is enough for me,” Jefferson wrote to Dr. Rush. “I only needed this knowledge to revive towards him all of the affections of the most cordial moments of our lives.”

Jefferson and Adams resumed their correspondence, which took on an incredible depth and breadth. The two men still discussed politics, but they also talked about their own aging and their legacies.

Their friendship was so strong that the two men actually died within several hours of each other, on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Not knowing that his friend had already died, Adams’ last words were “Jefferson still survives.”