10 Must-See Yonic Artworks

Few subjects prove as controversial as the vagina. Yet some of the art world’s most captivating, contentious, and dialogue-generating works depict the female form. From Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party to Georgia O’Keeffe’s famous flowers, these are ten essential yonic artworks to know.

Black Iris, Georgia O’Keeffe

When American artist Georgia O’Keeffe’s now-famous flower paintings were first exhibited in the 1920s, they stirred controversy for their sexual connotation. Even O’Keeffe’s husband – pioneering photographer and avant-garde art promoter Alfred Stieglitz – was supposedly shocked. On view at the Met in New York City, Black Iris is a prime example of O’Keefe’s allegedly sexually-charged botanical depictions. Amidst the growing popularity of Freudian theory, many critics drew comparisons between O’Keeffe’s flowers and female genitalia, though the artist herself later dismissed sexual interpretations of her work, stating, “you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower — and I don’t.”

L’Origine du Monde, Gustave Courbet

Thought to have been commissioned by a Turkish-Egyptian diplomat and later owned by controversial psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, French painter Gustave Courbet’s frank, up-close portrayal of female genitalia remains controversial 150 years later. In 2009, Portuguese police confiscated copies of Catherine Breillat’s book Pornocratie for featuring L’Origine du Monde (1866) on its cover, and since 2011, Facebook has attempted to ban users from sharing the painting.

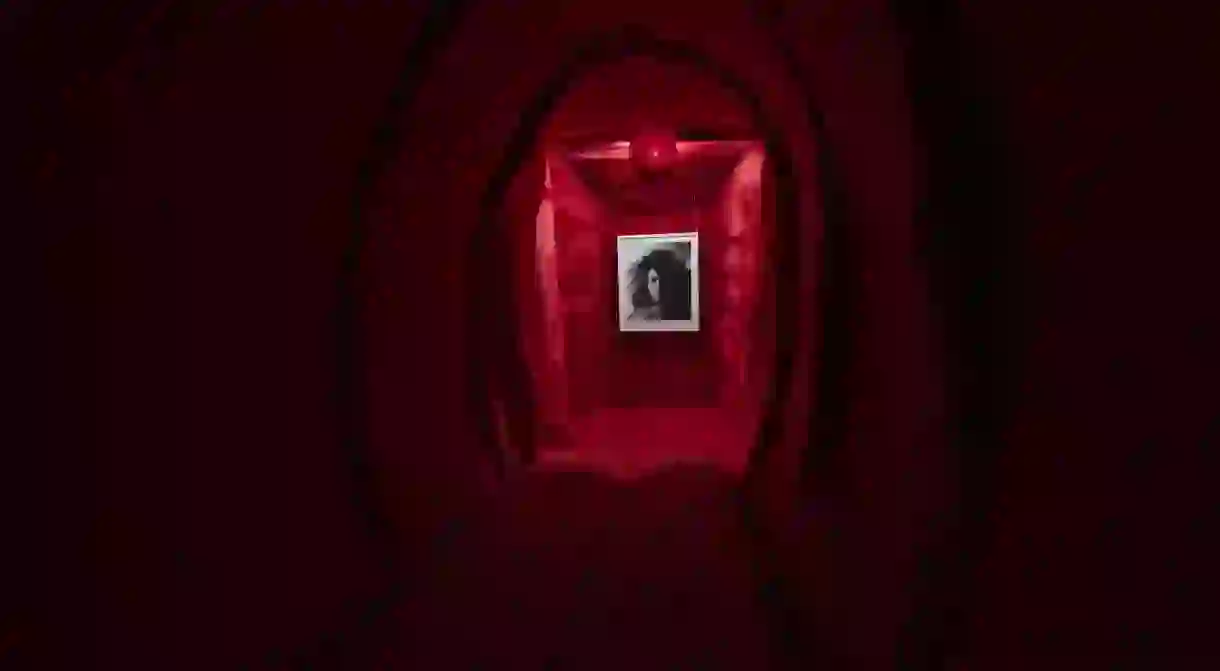

The Two Talking Yonis, Reshma Chhiba

South African artist Reshma Chhiba’s exhibition, The Two Talking Yonis, sparked controversy and admiration at its unveiling in 2013 at Constitution Hill’s former Women’s Jail. The exhibit featured a velvet-lined tunnel with a soundtrack of shrill screams and mocking laughter. Some have condemned the work as “pornographic,” and others, like then deputy CEO of gender equality group Gender Links, Kubi Rama, praised it for bringing women’s issues into the mainstream dialogue. Chhiba defended her work, stating, “you don’t often hear men talking about their private parts and feeling disgusted or shamed. And that alone speaks volumes of how we’ve been brought up to think about our bodies, and what I am saying here is that it’s supposed to be an empowering space.”

Pussy Boat, Megumi Igarashi

Japanese artist Megumi Igarashi, also known by her pseudonym, Rokudenashiko (which roughly translates as ‘good-for-nothing girl’), has dedicated much of her career to challenging what she views as discrimination against dialogue about the vagina in her homeland. Her recent Pussy Boat project – a kayak crafted from a 3D scan of the artist’s own vagina – openly confronts the taboo she wants to change. After successfully raising funds for the project via a crowdsourcing campaign, Pussy Boat made its maiden voyage on Tokyo’s Tama River in 2013. However, less than a year later the artist was arrested for sending files containing a 3D scan of her genitals to project donors and subsequently fined for distributing ‘obscene images.’

Chacán-Pi, Fernando de la Jara

Commissioned by Germany’s Tübingen University in 2001, Peruvian artist Fernando de la Jara’s 32 ton, 14-foot-high sculpture, Chacán-Pi, gets its name from a Quechuan word meaning both a “place where water has tunneled through a mountain,” and “lovemaking.” It was created by the artist as a celebration of the tactile experience of the body. The sculpture hit the headlines in 2014 when an unnamed American exchange student, seemingly acting on a dare, decided to closely investigate the artwork and proceeded to become stuck inside the sculpture. Fernando de la Jara took the incident in good spirit, stating, “it’s participatory art. It should be entered.”

The Dinner Party – Judy Chicago

Hailed by the Village Voice in 1979 as “the first feminist epic artwork,” American artist Judy Chicago’s, The Dinner Party, is today the focal point at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at New York’s Brooklyn Museum. A large-scale installation composed of a huge triangular table set with 39 place settings celebrating important women through the ages – from Boadaceia to Susan B. Anthony – featuring a vulva-esque dinner plate, The Dinner Party was created by Chicago with the aim of ending “the ongoing cycle of omission in which women were written out of the historical record.”

Casting Off My Womb, Casey Jenkins

Australian performance artist and ‘craftivist’ Casey Jenkins’ work, Casting Off My Womb, was a 28-day performance marking one full menstrual cycle during which the artist knitted from a skein of wool inserted in her vagina. The performance caused quite the stir amongst less discerning internet circles when it was shown online in 2013, denouncing her work as “disgusting.” Rather than back down in the face of misogynistic internet trolls, Jenkins instead embarked on another vaginal knitting project: incorporating the hate comments she received online by knitting them into scarf-like scrolls using wool soaked in menstrual blood.

Dirty Corner, Anish Kapoor

Created in 2011 by British-Indian sculptor Anish Kapoor, Dirty Corner is a huge 60-meter-long, funnel-shaped work crafted from steel and rock, described by the artist as representing “the vagina of a queen who is taking power.” The piece was first shown at Milan’s La Fabbrica del Vapore and most recently exhibited in the gardens of France’s Palace of Versailles, where it sparked outrage for its overtly sexual nature. The sculpture courted further contention in late 2015 when vandals scrawled anti-Semitic slurs on the work, and Kapoor controversially called for the graffiti to remain as a testament to societal intolerance. A subsequent tribunal in Versailles ruled for the graffiti to be removed, and Kapoor opted to cover Dirty Corner in gold leaf as his “royal response” to the vandals.

Hon-en Katedral, Niki de Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely, Per Olof Ultvedt

A monumental collaboration between French artist Niki de Saint Phalle, Swiss sculptor and pioneer of kinetic art Jean Tinguely, and Swedish artist Per Olof Ultvedt, Hon-en Katedral (which translates to “She–A Cathedral”) was a large-scale sculpture exhibited at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet in 1966. Taking the form of a reclining woman, the 28-meter-long Hon-en Katedral was an immersive art experience that invited viewers to walk through the body of the sculpture via an entrance at its vagina where they were greeted by various rooms, including a cinema and a milk bar strategically positioned in the sculpture’s right breast.

The Great Wall of Vagina, Jamie McCartney

A self-funded artwork five years in the making, English artist Jamie McCartney’s The Great Wall of Vagina is a nine-meter-long wall sculpture crafted from the plaster casts of 400 women’s vulvas, created as a means of combatting genital anxiety and the cosmeticizing of the vagina via art. Exhibited at Milan’s La Triennale museum in 2013 and later at London’s Mall Galleries as part of the 2015 Passion for Freedom Art Festival, The Great Wall of Vagina has since been cited in many educational and medical texts for its championing of female body positivity.