Inside the Controversial USA Yoga Championships

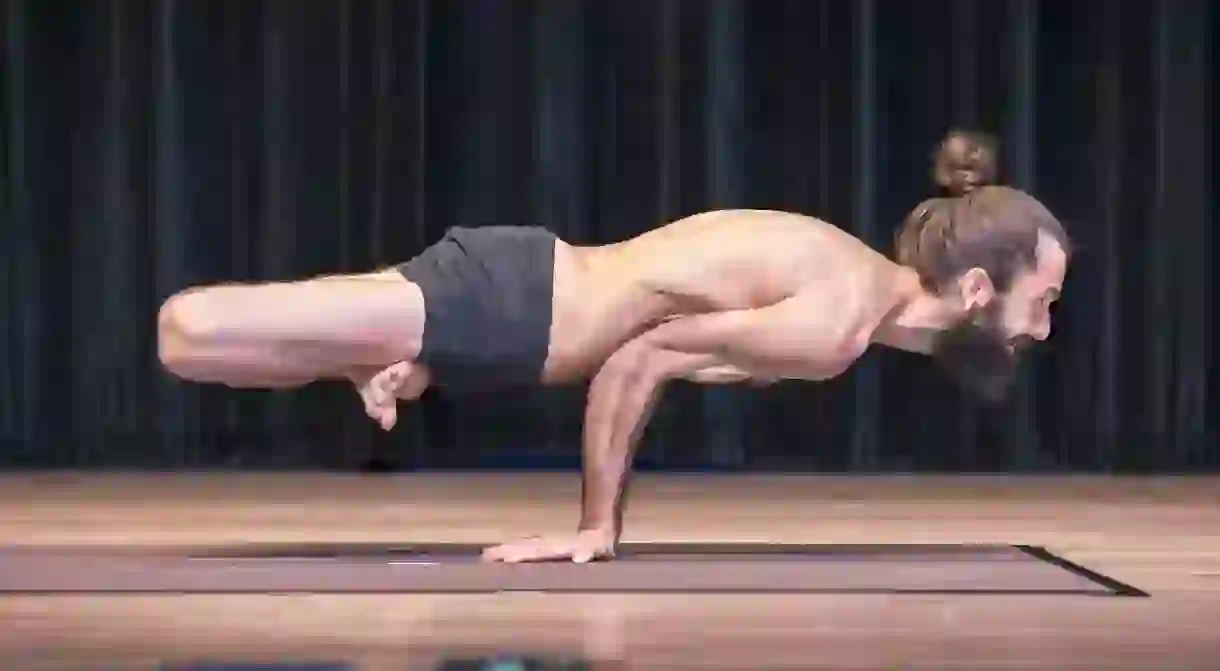

The USA Yoga Championships sees yogis from across the country performing postures in a competition that scores them on alignment and stability. Is a posing contest a betrayal of yoga’s roots or a way to further increase its appeal?

Picture yourself on a spotlit stage in front of a panel of judges and several shadowy rows of spectators. The small auditorium is so quiet you can hear the pounding of your heartbeat. The cue “begin please” signals the start of your demonstration. You have exactly three minutes to complete a six-part routine, comprising four compulsory postures – a forward compression (like standing head-to-knee pose), a backward bend, a traction (like standing splits) and a spinal twist – plus two additional postures from an approved list. You and the other contestants will be scored on the precision of your alignment and your ability to remain stable in the pose for a minimum of three seconds while adrenaline floods your system.

Welcome to the USA Yoga Championships, an annual competition that attracts ambitious, experienced yogis from across the country, all of whom hope for a medal and the kudos of being an asana champion. The competition is organized by USA Yoga, a non-profit founded by Rajashree Choudhury (ex-wife of Bikram Choudhury, the disgraced hot yoga guru accused of sexual assault). It’s one of many organizations contributing to a global movement that aspires to make yoga an official Olympic sport.

The history of competitive yoga is opaque. The International Federation of Sports Yoga states that yoga competitions can be traced back some 2,000 years, though this was more likely to have consisted of philosophical debates than posture demonstrations. The first recorded competition took place in 1975 when Yogamaharishi Dr Swami Gitananda Giri Guru Maharaj founded the Pondicherry Yogasana Association and began hosting youth championships in India. Fourteen years later, in 1989, the first World Yoga Cup headed by Swami Maitreyananda, founder of the Latin American Yoga Union, took place in Uruguay. In 2019, there are yoga championships in countries all over the world, plus coaches who specialize in preparing would-be champions and hundreds of competitors vying for victory.

Victoria Gibbs, a former ballet dancer from New York, entered the USA Yoga Championships on the recommendation of her yoga teacher. Her innate poise and familiarity with performance under pressure made Gibbs a natural competitor. Ideally, Gibbs would increase her practice leading up to the competition, but after being diagnosed with lupus in 2016 – an autoimmune condition that foiled her first attempt at the competition, leaving her physically depleted – she has to prioritize rest instead. Occasionally, though, Gibbs performs her routine in front of her yoga teacher and fellow students to get feedback and encouragement.

In 2018, Gibbs sailed through the nationals to represent the USA at the World Championship of Yoga Sports in Beijing, an international event organized by the USA Yoga-affiliated International Yoga Sports Federation.

“When I did really well I cried because it had been so many years coming, and there were so many things that have plagued me mentally during my past demonstrations,” says Gibbs. “I’ve never been able to do what I consider the best of my ability. So last year it was super emotional because I was feeling really good, and everything was mentally balanced. And it was like, this is the next phase of my growth as a person.”

For her, the appeal of the championships is the challenge, not just physically but mentally. The competition, the element of performance, the adrenaline, the medal – they add another dimension to her yoga practice. It’s a sense of accomplishment that group classes at her local studio don’t seem to provide.

“It’s mostly a competition within yourself,” Gibbs explains. “It’s about how you wake up that day, how you’re feeling, how you approach your demonstration, and really that meditative aspect of being able to get up on stage and block out everything and everyone around you. It’s a very humbling experience.”

There’s no denying that the physical element of yoga can be very athletic – a blend of flexibility, strength and balance that happens to be beautiful to watch. However, labeling it a sport, as USA Yoga does, feels wrong to many yogis. According to The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, an ancient Sanskrit guide to living a yogic life penned by a mysterious sage, there are eight limbs to yoga. These ethical guidelines, spiritual disciplines and moral codes form a roadmap to samadhi – eternal union with the universe. Ignoring seven of the limbs to focus solely on the physical one seems reductive at best.

To support its stance, USA Yoga brings out the big guns – a letter of approval from one of the founders of modern yoga, BKS Iyengar. His endorsement reads: “Out of the eight petals (limbs) of yoga, the only petal that is exhibitive is the yoga asanas, whereas the other petals are very individual and personal. As such, there is nothing wrong in holding a competition on the qualitative presentation of yoga asanas. The presentation must be very natural with innocence and humility rather than pride and arrogance. Then I consider such competitions as healthy.”

Yoga has continually evolved over the course of its 5,000-year history. Increasingly, the physical poses are being adopted and adapted without integrating the spiritual aspects, and USA Yoga doesn’t see this as a bad thing. The organization’s goal, to some extent, is to separate the practice from religious affiliation – a perceived necessity for it to be taken seriously as a sport for the masses.

“Just as meditation has been secularized, it’s important for yoga to be in order for more people to adopt it,” says Ainslie Faust, executive director of USA Yoga. “We’re only judging yoga asana. You can’t judge somebody on their spirituality.”

According to the latest Yoga in America Study conducted by Yoga Journal and Yoga Alliance, approximately 36.7 million people took a yoga class in 2016. While the top reason for taking up yoga was increased flexibility (61 percent), those who have a regular practice cite its deeper and more profound effects – mental clarity, for example – as reasons to keep returning to the mat. You need only look at the increasing popularity of teacher-training programs (for every current instructor, there are two yogis who want to teach) to recognize that curiosity regarding the history and traditions of yoga is flourishing. Perhaps it doesn’t matter how people find yoga, just that they find it in the first place.