'Get Out' Composer Michael Abels Details Why Working With Jordan Peele Was a Dream

Rotten Tomatoes might currently rate Get Out at 99 percent, but it will always be a perfect score in our hearts.

We could go on and on about how Jordan Peele’s directorial debut flawlessly portrays racism within a suburban setting and the problems of the white gaze, how it confidently balanced classic physical scares with a far more insidious, vaporous monster (which for many was viewed through a mirror, although not necessarily head on). How, in a moment, audience members would simultaneously feel like laughing and crying, feel intense anger and the desire to collapse into themselves (or maybe better, the “Sunken Place“) in shame. How it all ultimately added up to a freshened outlook on systematic racism that needs to contemplated and discussed with your friends for days because you just watched a horror film.

While the Key & Peele graduate’s success has been praised to no end, from the socially woke stoner to The New Yorker—and most deservedly so—it’s also important to acknowledge a factor that so often goes uncredited: the score. Given that a deserving screenplay is provided, a thoughtful musical arrangement is crucial to a movie’s success, but unless a headlining name like John Williams or Hans Zimmer is attached to the project, or the film is an outright musical, few composers get the nod they deserve.

Few people would probably recognize Michael Abels’ name outside of the orchestral concert circuit. The director of music for New Roads School in Santa Monica, California, Abels was discovered by Peele, thanks to his composition “Urban Legends.” As Abels explains it, the concerto begins with his version of a scratching record before “all hell breaks loose,” and so Peele decided “this guy could terrorize some people in this movie.”

Speaking with Abels over the phone, we discussed how the composer incorporated “black roots” into the score, why working with Peele was a dream, and the piece of music in the film that sounds like “a really bad erectile dysfunction commercial.”

Culture Trip: Get Out is more complex in its emotions and intentions than most films, constantly switching from horror to love story to comedy, and even some where it is funny and terrifying at the same time. How did this affect the way you composed?

Michael Abels: It was really specific in that I noticed the comedy in those moments right away, and there was even a scene—the earlier part of the garden party, not what I call the “fist shake” moment, but the earlier part where all of the guests are saying awkward, inappropriate things to him—all the white guests, anyway. I thought that was very comedic, so the first cue I wrote for that was kind of an early Baroque concerto, kind of like Vivaldi, because I thought it’s funny, summery music, and it really reflects what the characters would be listening to at that party. But Jordan said no, this has to be told from the lead character’s perspective. This was really smart because what it means is that we are aware of the comedy moments in the film, but they occur as awkward moments of reality.

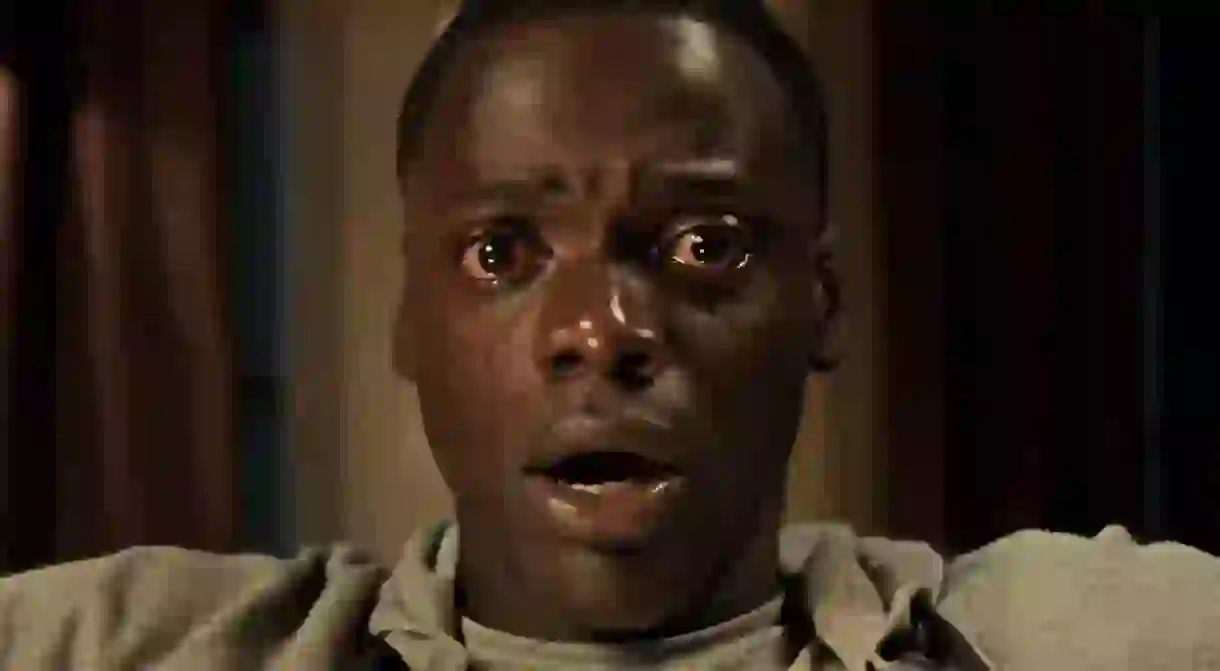

There’s two types. There’s that type in the garden party where what they say is funny, but it’s funny in a way where you’re disappointed in how hard they’re trying and how poorly they’re succeeding. In those moments, the score doesn’t react at all, it’s played purely from [Chris Washington’s, the lead role played by Daniel Kaluuya] perspective, and then Chris is uncomfortable, the music is uncomfortable. But then there’s the comedy that’s of his friend Rob, the TSA agent—who’s the funniest thing ever—and those scenes have no music whatsoever, and it’s because those scenes represent the reality check. It’s the comedy of truth. So the score is used to create the smothering and the inevitable and fateful world that Chris finds himself in in Rose’s parents’ house.

CT: It really goes to show how much a moment in a film can be controlled by the presence or lack of music.

MA: The educational video that explains the coagulate procedure and how he’s an important part of this grand experiment. There’s a really lame, terrible piece of music that I wrote for that video, and that’s deliberately bad because it’s supposed to be this homemade video that the Armitage family put together to help educate the lucky Negros who get to experience this little experiment. Then, they took what I did, which was bad enough, and made it sound like it was coming out of a TV show from the 1950s.

CT: Peele stated in an interview that he wanted you to create a score that had this “absence of hope but still had black roots,” and that he wanted the voices to represent those who suffered through slavery and other racial injustices throughout history. Considering that African-American music is often hopeful in its sound, how did you approach striking the balance he desired?

MA: He’s so eloquent in capturing what the challenges are and distilling it down. What I did was I used black voices, but I used very dissonant harmonies that you wouldn’t find in, say, traditional gospel music. You hear the vocal quality you’re used to in that hopeful music, but you hear the harmonies that you’re used to hearing in a horror movie, and it’s a definite contrast.

One thing Jordan said was that strange-sounding lyrics are scary. He gave me this list of different things he thought were scary and on it was foreign lyrics where you can’t understand what they are saying, and it’s true. So I chose Swahili because it’s an African language and it’s a musical language, even though it may not be the language that most of the slaves spoke, but I needed a little bit of artistic license to make it work.

CT: Can you translate exactly what is being said in the main title,“Sikiliza Kwa Wahenga”?

MA: It translates as “brother”—which I left “brother” in English because of how rich it is when black people say brother, what that means, there’s just no translation of that —they say “brother, kimbia,” which means “run,” and then “listen to the elders, run away, listen to the truth, save yourself.”

CT: Was there a significance to having this warning of “run away” right from the start of the film?

This was the first track I wrote, and I wrote it even before the film was shot, just based on the first meeting with Jordan and talking about the tone of the project. He didn’t let me see anything until he had a rough cut, so there was a few months elapsed, and then at some point he said he was going to use “Sikiliza Kwa Wahenga” as the title track. Of course I was thrilled, but then I had to find a native Swahili speaker to make sure the lyrics really said what I thought they did. You really don’t want to get that wrong.

CT: Besides the voices, what other African-American nods are there in the score that maybe some people might have missed?

MA: There’s a tuned-percussion kind of bowl sound that happens a lot in… medium moments of tension, let’s put it that way. I didn’t have a checkbox of African instruments or African influences or African-American influences, but it was important that even though the score referenced older suspense films, it would still feel like it’s happening today, and I think that’s the African-American influence in it to me.

CT: There’s a lot of building strings that fall into dissonant frenzies and big drum hits for the jump scares, but you also use a harp a lot, which isn’t exactly the most common instrument found in a score—not least in a horror film. Why did you choose to include so much harp?

MA: What the film does so well—well, it does a lot of things well—it manages to straddle about two or three genres better than any film I’ve ever seen. It’s really a suspense thriller; it’s not a horror movie by my definition. By my definition, somebody dies in the first reel, certainly in the first 20 minutes. That doesn’t happen in this film. There’s a monster, but it’s about slowly revealing who that monster is. In the classic suspense film, the score is much more of a drama, and so the parts of the film that are a thriller need to play just like a thriller. So strings would be the natural choice to give it that rich, harmonic language of a Hitchcockian thriller.

And then the harp has this very delicate quality to it, most of the time. What the score provides is very subtle coloring, and there’s really no instrument better than the harp to be able to unobtrusively give that emotional musical quality.

CT: The harp has always been a very hypnotic instrument, and that’s definitely a big part of the movie.

MA: Exactly. After we had decided where “Sikiliza Kwa Wahenga” would go, the first scene that I scored that was really purely underscoring was the hypnotism. Obviously, it’s crucial to everything that happens in the film, and so I thought that if I could come up with a sonic palette that Jordan could agree to and approve, then I would not only have instrumentation but also some themes that I could use for the rest of the film.

CT: You’ve talked about it a little bit already, but can you describe what it was like working with Peele? How often were you sitting down with him, what directions did he give you, etc.?

MA: I gotta say, it was really a dream because he’s so smart and he’s so modest, and he enjoys the collaborative process. You put all those things together and you can’t help but have a good experience. He’s very able to express what he wants and he paints very colorful word pictures. For example, for that educational video, he said, “the music needs to sound like a really bad erectile dysfunction commercial.” I said, “I promise I am your go-to guy for your horrible erectile dysfunction needs.”

CT: I think most people would agree that comedians have this ability to get to the truth better than just about anyone else, and it’s really cool to see when someone who has long been embedded in the comedic circle step out into a new form, but with the same precision.

MA: One of the things that impressed me on first meeting was that he has seen every horror or suspense film that’s been made. He’s quite an aficionado of the genre, and with the films that he likes, he’s able to excite exactly what works about them. While he may be known as a comedic actor or a comedy writer, this film represents one tool he’s had in his palette that he’s had his whole life, and this is the first chance we’ve had to see it.

While Abels’ is definitely eager to work more with film, he most recently premiered “Liquify” with the Quad City Symphony, and is currently writing a wind orchestra piece for the West Point Band. If you are interested in scaring the absolute shit out of yourself sporadically throughout the day, you can purchase the Get Out soundtrack on iTunes.