Following The Subconscious Without Self-Censure: An Interview With Jen George

We spoke with the writer of the sleeper hit story collection The Babysitter at Rest about her unanticipated writing career, the influence of visual art, and not being afraid of your own imagination.

I discovered the work of Jen George through word of mouth. Several mouths actually—George appeared like an outbreak of Baader-Meinhof: within a year of publishing her first story, which also occasioned her first literary honor, all five of the fiction pieces in George’s debut collection The Babysitter At Rest—now out with the forward thinking, feminine press Dorothy Books—had been placed in magazines. Though I kept seeing her name appear and had heard good things, I really sat up when someone tweeted how a friend had ripped an excerpt of George’s story “Instruction” out of an issue of Harper’s and posted it to her. My curiosity became urgent—I was missing out.

Reading the The Babysitter At Rest is like imbibing a sort of literary ayahuasca. Its stories are placed within phantasmagorical settings and among chimerical characters, but their purposes go further than being merely macabre: they confront what identity means when it is constantly subject to change with age. In one story “Guidance / The Party” a Virgil-like figure guides a 33-year-old woman through the preparations for her first adult party. In the title story, a babysitter plays paramour for her employer—an enigmatic and married chemical plant owner whose son, we are told, is to remain in infancy: “Your father’s good looks and his property will never be yours because you will always remain a baby,” she tells the child, adding “It is better this way.”

At the book launch for The Babysitter At Rest, George acknowledged the influence of The Hearing Trumpet, a novel by the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington that has been called “the Occult Twin to Alice in Wonderland.” George’s stories also bring to mind the eldritch tales of Ontarian and fellow White Review alum Camilla Grudova, as well as the the dreamy narratives of the Uruguayan writer Felisberto Hernandez, once referred to as “a loopier, vegetarian Kafka.” Once could make a number of imaginative contrasts to George’s work, and in the end they would all amount to acknowledging her phenomenal originality. She was also kind enough to answer a few questions about newfound writing career.

* * *

You’ve had a different trajectory as writer than most people. Your first ever public reading ever was this past week despite having stories in many notable publications. In fact, it’s only been a year since Sheila Heti chose the title story from your new debut The Babysitter At Rest as the winner for Bomb’s fiction prize in 2015. Could you talk about what it’s been like to see your work go from being private, to the decision to share them, and the quick praise and subsequent publication they have received?

It’s been encouraging. I thought it’d be terrifying having work in the world- to have this thing you’ve committed to with your name on it that people can reject or dismiss, and also define you by, but it’s actually been fine—both because I haven’t really paid attention to the book as a product in the world, and because I’ve been fortunate enough to deal with very nice people who are inviting and welcoming and friendly and understand the book. I think I expected people to tell me I didn’t belong, but for the most part that hasn’t happened. Just before I submitted the title story to BOMB I thought I’d stop writing. I’d been working in isolation—I had no one at all reading my work, most people I know didn’t know that I wrote. But after awhile working in a vacuum starts to kind of disappear the work, or your drive to make it.

I’d come to a point where I thought I should maybe stop writing and try to lower my ambitions and get a decent paying job instead of a bad paying job, even though I’d never successfully done that before. The only reason I submitted the title story in the collection to the BOMB contest was because the judge was Shelia Heti, who I thought might like it, and because I actually read BOMB—it was kind of a first attempt and a last ditch effort to put my work into the world. The story that was submitted was initially rejected by interns—it didn’t make it to the editors, so it didn’t make it to the Shelia Heti, but then Shelia Heti went back and read all of the contest submissions and saved the story from the slush pile. Had that not happened, I don’t think I would have submitted anywhere else. The experience of having work that’s been well received by the people or places I regard highly has been nice—it’s like I’ve been given the permission or opportunity I’d needed to keep writing.

You utilize feminine, uncanny, erotic, and domestic tropes to magnetic effect. Different details come to forefront with each read, many of them are bizarre, but somehow always comprehensible in the way dreams can be. When you are piecing these stories together, do you let your imagination go “off the leash” so to speak? Are you ever made uncomfortable by where it takes you?

I’d say I trust in imagination as part of the process—but imagination can be called other things, like subconscious or intuition. It’s from that more subconscious place that the things you mentioned sort of come together, or at least are not as categorically separate as they are in daily life. I see the uncanny fictive space as a distilled reality where hidden thoughts and ideas behaviors and energies become magnified. We learn how to order our worlds and language so that we can understand our surroundings and function and fit into the world we’re perceiving, and in this book I was interested in what happens when the behaviors and beliefs and perceptions that make up a person or a partial life start to come undone, and how the performance of these things without connection is just that- performance—and I was interested in what lived in that space—which turned out to be a lot of things I had not necessarily anticipated.

I was interested in this landscape where there are fewer barriers between concepts, or where things are more conceptually collapsed, and in focusing on characters in these worlds where their internal perceptions take up the entire frame. I don’t write with an outline, and most of the time without an idea of what I’m writing in a larger conceptual sense, so in that regard I let my imagination or subconscious take over. I’ve come to trust in those things as part of the creative process rather than see those things as being self-indulgent. Imagination is a good source to draw from— it’s kind of like how kids play, they aren’t sitting around worried about holes in linearity or narrative leaps—like how will it make sense to get from this planet to another, how is this person flying, how are they breathing underwater and drinking tea underwater, how are we in outer space now—they just make these jumps, and logic around the narrative kind of falls into place and things appear as they need to.

I think I follow the subconscious or intuitive without much self-censure, so that’s where a lot of the sex in the book comes from. I find sex and the body to be very relevant to the work—to this book in particular. I don’t set out to write about sex but it always comes up, almost how it does in dreams—it’s just there. If people reading certain things in the book are uncomfortable, I think that’s sort of an interesting result of the product of the book, though I can’t say I felt uncomfortable writing it. I think it’s actually a strange idea to be uncomfortable or embarrassed in the very internal space of writing or creating anything—like this is stuff I think about, so it’s a territory that should be explored- otherwise what’s the point. At times when I think about people I know reading it, that’s a little different—especially when they’re not looking me in the eye while telling me the book is racy or gritty or using these other code words that mean sexually graphic and weird.

So, maybe then I’m a little uncomfortable, like in a polite-society sense, when we’re eating dinner together and the person who has read my book is maybe imagining an older man sticking his finger up my ass, as though this is a memoir, but even with that I’m interested in what’s past embarrassment, or in not seeing embarrassment as something that just shuts you down—I think a lot of people just stop when they get embarrassed, I think I used to just stop there. I think it’s important to move through it, I’m interested in what’s past that point, both personally and in my work.

Before this you were working on a television pilot In the Production Office, which you both wrote and starred in. How does fiction and screenwriting play off of each other in your mind? Are you still interested in working in film as you continue to write fiction?

I haven’t thought about filmmaking in awhile. I spent a lot of time with this collection and now I’m writing a novel, so I’ve been in that internal space that writing fiction kind of requires or creates. I think fiction has always been the more natural fit for me. Filmmaking has so many moving parts- I never figured out how to make it work the way I wanted. It requires such a different type of energy than writing alone. I think it’d be a challenge to return to because I’d have to approach it in a totally new way. I have no idea how to set about doing what I’d like to with film, which sounds kind of exciting because if I tried to do something in film, even just screenwriting, I’d have to think about a whole new set of creative and logistical problems that don’t exist when you have control over your world and your product the way you do with fiction. I’m attracted to the collaborative aspect of filmmaking, and even screenwriting, where you have to willingly surrender identity or control in a way I haven’t had to do for years, but at the same time I’ve been pretty satisfied with how autonomous fiction allows me to be.

You seem to have a strong connection to art—both Matthew Barney and Miranda July are admirers of your work—and you’ve mentioned your own admiration for people such as sculptor and filmmaker Mike Kelley and the surrealist painter and writer Leonora Carrington, especially her novel The Hearing Trumpet. Could you talk about how your relationship to art and artists has informed your writing?

I’m interested in the approach to narrative that I see in visual and performance art, and the conceptual perversion that occurs in those spaces, and the subversive product of those mediums. Seeing or being around visual and performance art are really effective in making me think differently or more clearly or even just feel excited about possibilities in making my own work. I don’t have formal training, so I probably don’t consider text alone as holy as maybe people who have more of a formal literary education. The things I’ve been interested in, both with text and art, are the things I’m instinctively drawn to or get kind of obsessed with or possessed by more than what’s maybe considered good or fashionable- I’m pretty ignorant about certain writers or artists that maybe I should know.

I’ve always been a more internal person, or maybe just alone, and I’ve pieced together what I like by finding things I could make personal from a lot of different places, so I think that’s reflected in my work. When I was a teenager on my own in Oakland I got into reading these heavy esoteric texts I didn’t quite understand and all this advanced astrology stuff I really did not get, but read anyway, and that way I learned how to kind of take things and read them in my own distorted manner and make them my own. College wasn’t really an option for me because I came from a large family without much money-from the time I was a teenager I had to work full time to pay rent and to eat, I’d found high school boring and miserable, but books and art always appealed to me—I always wanted to be a writer.

When I first moved to New York, I worked at the old Shakespeare & Co. on Broadway—which is now a Foot Locker, I think. That job paid minimum wage, but we could read all day, so when I worked downstairs where all the plays and political books and philosophy were kept, I read a lot of plays and philosophy all kinds of communist and socialist texts that made an impression. We had the booklists from all the classes at Cooper Union, so I’d give the students, who were my age, their stacks of books, and then I read whatever was on their reading lists, from more fundamental stuff like all the Russians, to more abstruse stuff, lots of French and German philosophy—that’s also where I first read DeBeauvoir and Beckett and other authors and books I liked that I maybe wouldn’t have been otherwise exposed to at that young an age. I read without any context, no class or teacher to kind of anchor the work, no one to talk with about the stuff in the books, and no past literary experience from which I could contextualize the work myself, so everything was just very internal and filtered through my personal lens.

In general I think I have a strange and maybe wrong way of reading things since it’s so outside of any academic training, but I think that’s actually a good place to work from, or maybe the only place to work from since the personal is most primary. There’s some osmosis or alchemy that occurs just by being with or around something—that’s partly why performance can be so powerful. When I started paying attention to visual art, it was like that—I liked the energy of certain things, or was around certain work that I liked. Visual and performance art seemed like a way out of straight or everyday life and a way into a life I wanted for myself, so I started paying attention to visual art in the way I’d read other things I maybe didn’t get at first, and then after awhile visual art became an equal, or at times greater, creative source for me than literature. I find the product or involvement of visual and performance art almost more experientially communal because these forms are so open to interpretation and tend to be more conceptually and physically experimental, with higher stakes and a higher risk of failure than you generally see in something as polished as a published book. I think I’m inspired to raise the bar for my own work most when I see art that I find really great, maybe more so than when I read a great book and just feel sort of overwhelmed.

I’d picked up The Hearing Trumpet when seeing Leonora Carrington’s name on the cover of the book because I’d remembered seeing Self-Portrait at the Met years earlier, and that image and her name had stuck with me. The book was kind of the same as the painting- mesmerizing and whole and totally unique and radical. Her worlds are so full. Reading that book was kind of like the last piece of the puzzle for me after internalizing so much work and seeing a way I could actually make something. So, in that sense, I think anything I write is homage to Carrington because without her example I doubt I could have understood that making work I wanted to make was possible, that I was allowed enter these stranger territories though fiction. So I had her in mind when writing, and at the same time I was around a lot of (literally and figuratively) big work by male artists, which in certain physical aspects was polar to Carrington’s work.

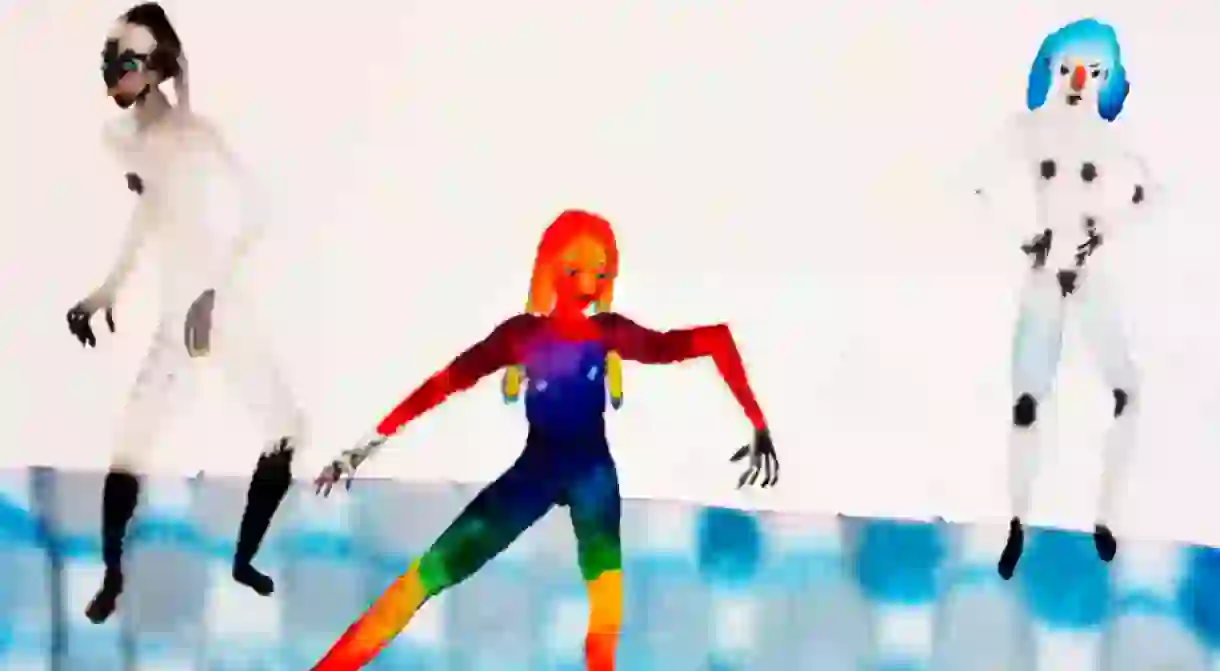

During the time I was working on this book, there were all these huge exhibitions and retrospectives in the city that were almost exclusively the work of men, which wasn’t at all new or surprising, but I started thinking about it in a different way. I felt really inspired by Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley and their work informed how I thought about narrative- especially Mike Kelley’s Day Is Done and Extracurricular Projective Reconstruction #1 (A Domestic Scene) and Odalisque, all of which influenced how I thought about constructing the narrative in the book. But this same work that was proving to be a creative source also had a direct influence on the larger narrative of the book in a more meta sense because I became interested in the place of the unrealized female artist in the space of an abstracted patriarchal capitalist art and political culture, and I became interested in viewing that space pretty exclusively from the perspective of the young female. As a result, this book is pretty connected with visual art and with specific artists.

If I remember correctly, you were previously working on a novel that you were “determined to handwrite,” before putting it down to focus on the stories that would become The Babysitter At Rest. Has finishing these stories given you a better sense of how to return to novel writing? And are you working on something at the moment?

Before starting this collection, I’d been writing by hand after not writing for a bit and it turned out to be a really creatively generative process and a novel started to develop. The handwritten novel kept growing, and at no point did it occur to me to put it on the computer. I started seeing this bigger picture for that novel and soon notebooks were filled with kind of frantic handwriting, and then every page of every notebook was filled with dozens of post-it’s that were notes on characters, relationships, lines of dialogue, and references to other points in the book that were lost in other post-its. It got really out of control and I got to a point where instead of being excited about it, I looked at the notebooks with dread- like there is no way I can ever transcribe all of this and this story is so huge.

When writing this collection I learned how to be a lot more disciplined in the process—not chasing every single thing that came up, and writing on a computer so that I could keep track of things that did, so I was able to focus in a way I wasn’t when writing by hand. This collection was a lot more controlled than that novel was. I think I learned that I had to be able to move things around physically, like cut and paste lines and whole paragraphs. Writing this collection taught me how to make things as full as possible in a controlled space, how to maximize what the form will allow, and how to be more centered in the work in a way that I hadn’t been previously. I’m currently working on a novel about a women’s art collective—I’m still in the in the early stages, but so far the process is very different than it was with Babysitter.

THE BABYSITTER AT REST

by Jen George

Dorothy | 168 pp. | $16.00