Face To Face With Fear: 13 Paranormal Literary Works From Around The World

We live in fear; we love our fear. It keeps us out of danger, yet we seek it out for thrills. In the realm of the supernatural, fear is what drives our imagination to unexpected reaches. With clandestine practices such as Paganism and Voodoo, fear of their customs can lead to even scarier forms of prejudice. In literature, fear and horror have long been celebrated tropes, arguably touching upon the folklore of every single culture on earth. Here are thirteen spooky examples from around the world, including classics that highlight Haiti’s zombies and China’s devils, as well as more recent horrors both macabre and existential, like a Chilean office nightmare and a Nigerian take on Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

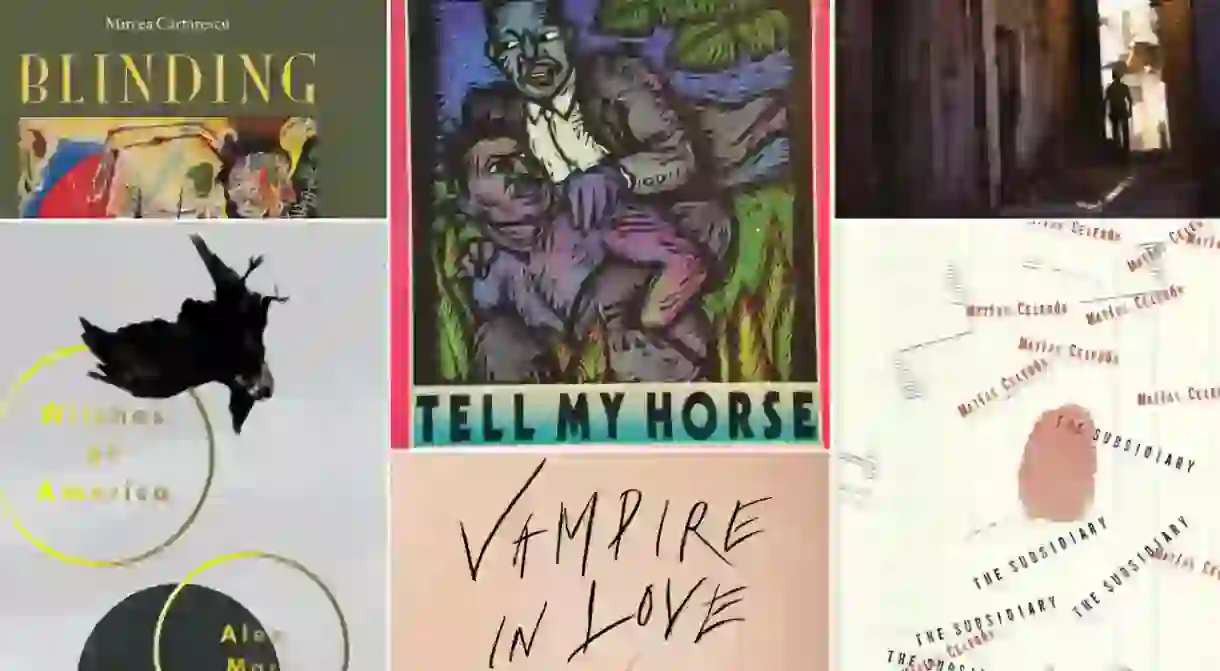

Alex Marr, Witches of America(USA)

Some people are born into a spiritual faith or community, others must go seek it out. Writer and filmmaker Alex Mar is of the later. Witches of America follows her five-year self-investigation into Paganism in its various branches across America. Her studies lead her to join a coven and learn the ways of witchcraft and its power as a matriarchal spirituality. As she gets deeper into her research, Mar participates in spells (she wants one placed on a rival for her lover’s affections) while at the same time learning how to respect the believers of one of America’s oldest traditions. Here, magic is intellectualized: “Magic works primarily through nonphysical means,” says a self-identifying witch, “that we can only observe in subjective ways.” What pagans call “unverified personal gnosis” and the concept of faith give a strong argument for individual subjectivity, all but uprooting the notion that some beliefs are more legitimate than others.

Enrique Vila-Matas, Vampire in Love (Spain)

Spanish writer Vila-Matas is primarily known in the English world for his meditative and comic novels about literary figures Bartleby & Co. and the art world, The Illogic of Kastel. In Vampire in Love, his first story collection to be translated in English (by Margaret Jull Costa), Vila-Matas is at his most macabre. Among Vila-Matas’ strange tales are a hunchback vampire named Nosferatu; a mute and demonic, fascist child; and a museum guard who kills herself only to find the afterlife just as irksome: “Happiness kills, and what those suicides are imitating is not the imitable, but the non-existent, thinks Rosa Schwarzer, recalling, too, that unreality is also unpleasant… she is beginning to feel uncomfortable in this incomprehensible culture, in this distant, mysterious place where death is celebrated.” Rare is a talent with supernatural ability to bring fuse genre and literary fiction, but Vila-Matas does it effortlessly. Be prepared to have your breath taken away…

Ahmed Saadawi, Frankenstein in Baghdad (Iraq)

It makes macabre sense that war-torn Baghdad would be an ideal setting for a Frankenstein story. Here, Dr. Frankenstein is a street scavenger named Hadi, who collects human body parts from the rubble-strewn streets of U.S.-occupied Baghdad, stitching those together to create a complete human corpse. His purpose is noble — he wants the corpse to serve as a statement to the government that the victims of war deserve a proper burial. The allegory takes an odd twist when Hadi’s corpse disappears and a grotesque murder spree ensues, the killer reported as a bullet-impervious monster that must replenish its skin with human flesh. This masterful contemporary Middle Eastern take on a Western classic gives the war in Iraq an extra degree of surreality. A new translation into English by Jonathan Wright will be published in July 2017.

Matías Celédon, The Subsidiary (Chile)

Though office existentiality has been around since Melville, and Kafka’s eponymic “Kafkaesque” now defines bureaucratic absurdity, outright office horror hasn’t really received its due. Three examples that come to mind are Die Hard, Vincenzo Natali’s short film Elevated, and this Calvin and Hobbes strip. In other words, office horror is a sub-genre that is still fertile for ideas, especially in literature. Step in Chilean novelist Matías Celédon, whose novel The Subsidiary carves itself a new niche. In fact the book isn’t “written” in the traditional sense — its 208-pages filled are filled with literal stamped notes that tell the story of a worker who is held in a corporate office during a black out. Eerily, only the loudspeakers work. The worker records both the announcements: “ALL PERSONNEL MUST REMAIN AT THEIR WORKSTATIONS” as well as his observations of the terror in the dark, such as when a pack of howling dogs enters the office floor. In a nice touch, even the English translation by Samuel Rutter is stamped.

Zora Neale Hurston, Tell My Horse (Haiti)

Sometime in the early 1930s, American writer and novelist Zora Neale Hurston set off to explore voodoo culture of Jamaica and Haiti. She may have been spurred on to discover the truth behind occultist William Seabrook’s Magic Island, a book which contains a sensationalist account of voodoo and zombies (it is credited as bring the word “zombie” to mainstream America). Her investigation resulted in Tell My Horse, a work of literary journalism in which Hurston explored voodoo culture by participating and documenting its ceremonies, customs, and superstitions. Most arresting is Hurston’s encounter with an actual “zombie,” a woman who her relatives claim to be their long dead and suddenly revived relation, Felicia Felix-Mentor. While Hurston sleuths out the truth about Felicia’s state (rumored to be caused by a powerful psychoactive drug) the zombie woman is taken to a hospital and wanders its grounds. “What is the whole truth and nothing else but the truth about zombies?” Hurston writes. “I do not know, but I know that I saw the broken remnant, relic, refuse of Felicia Felix-Mentor in a hospital yard.”

Mircea Cartarescu, Blinding (Romania)

What’s scarier than a zombie? How about an army of them, as well as brain-raping butterflies, spider-legged and snake-eating women, and secret police task forces. In Romanian writer Mircea Cartarescu’s Blinding, part one of an as yet partly-translated trilogy, the reader is taken through a fever-dreamed Bucharest that lies behind the Iron Curtain—though it might as well be the gate to Hell. The haunted magnificence of this vision is bookended by recollections of Mircea (the character)’s own childhood. His birth is where things get truly weird, as it transpires that Mircea’s coming into the world has been long prophesied, and that upon his birth would begin a new religion. Pushing the messianic fantasy to the maximum is a prose — translated by Sean Cotter — so magniloquent it sounds eerily philosophic: “the I of every moment is connected to the one before through a vigorous umbilical cable, with two arteries and one vein, moving the ineffable erythrocytes of causality.” Don’t be afraid to pick this one up, but be prepared to be locked in its spell.

Jeremias Gotthelf, The Black Spider (Switzerland)

In this classic horror tale, translated by Susan Bernofsky, a Swiss village is plagued by an arachnid infestation. This has been been a problem for generations, originating from the village’s foolish deal with the Devil; he often appears here dressed in monochromatic green, and at one point kisses one of the residents: “Christine felt as if her face was bursting open and glowing coals were being birthed from it, quickening into life and swarming across her face and all her limbs, and everything within her face had sprung to life, a fiery swarming all across her body.” Gotthelf, the pen name of a real-life pastor, isn’t shy about threading his story with allusions to the Old Testament, but then again, what good is a deal-with-the-devil story without a biblical contrast?

Mati Unt, Diary of a Blood Donor (Estonia)

Take Bram Stoker’s Dracula and place it within the context of the last days of Soviet-ruled Estonia, and you get Mati Unt’s Diary of a Blood Donor. Estonian Joonatan Hark (get the reference?) is summoned by a mysterious person to meet aboard a docked ship — the Aurora. In the meantime, Estonia is celebrating the birthday of poet Lydia Koidula who played an important role in the first Estonian independence movement. Unt constructs an absurdist’s interplay between Estonia’s political upheavals and vampires both symbolic and blood-sucking: “Yes, we need blood to live, but we no longer infect anyone, at least not in this little country, this Estonia with its surfeit of suffering and its many dilemmas.” Through Ants Eert’s hypnotic translation, Unt’s metaphoric language and meditations will have you thinking about vampires in a whole new light (or absence of it).

A. Igoni Barrett, Black Ass (Nigeria)

Like Kafka’s Metamorphosis in which Gregor Samsa wakes up to find himself an insect, Barrett’s debut novel Black Ass follows the strange case of Furo Wariboko, a Lagosian who awakens one morning to discover that he has become an “oyibo” (a white man) — save, of course, for his still pristinely-ebony buttocks. As an unemployed 33-year-old, Wariboko’s transformation completely alters his life: he is ignored by friends, gawked at by strangers, ripped off by cabs, and sunburnt, while at the same time and almost immediately landing a job. Though he begins to benefit from his new pigmentation, Wariboko must still navigate Lagos as a foreigner among his people, a scenario that Barrett uses to explore deeper Kafka-esque meditations.

Christophe Claro, Electric Flesh (France)

In this absurdist horror novel, an electric chair executioner name Howard Hordinary is made redundant with the arrival of lethal injections — thus making him sit around ruminating on the loss of his occupation, and figuring out ways to repopularize electric chair executions. That’s not his only obsession — Hordinary believes himself to be the bastard grandchild of legendary escape artist Harry Houdini. Claro twists the plot even further, delving into the dark history of electricity uses on the human body, and twisting Hordinary into a twisted individual who shocks himself while he masturbates. Inspired by Vollmann, Pynchon, and Danielweski (whom Claro has translated into French), this postmodern French novel, translated by writer Brian Evenson, often goes in intriguingly unexpected directions, just like a bolt of electricity.

Pu Songling, Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (China)

This classic collection of Chinese supernatural tales was originally published in English in 1740, but it wasn’t until Penguin published an edition in 2006, translated by John Minford, that they became widely available. Songling’s tales are unique in that non-human and supernatural entities — phantoms, immortals, devils and animals — are its main protagonists, placed alongside commoners and outsized officials. Songling cleverly used the paranormal to criticize the government and highlight its injustices. Yet these stories are engrossing regardless of their social dimension, serving to introduce a cosmology of the otherworldly to Western readers.

Muriel Spark, Ghost Stories (Scotland)

The doyenne of British postwar literature may be known to most as the author of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, but Dame Spark was also an accomplished short story writer. A few of her pieces, assembled in this collection, are sinister tales with a supernatural penchant — at least in the subtle, unsettling ways typically found in 19th-century horror. If her talent and affection for portraying prim and proper main characters is in these stories undiminished, she’s managed to make the disturbing elements (ghosts, mainly, and a little murder) fit in perfectly. Highlights include ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’, whose progressive intensity and twist ending ought to keep you shocked for a while, and ‘The Portobello Road’, whose supernatural premise is used as a biting commentary on human vanity.

Will Elliott, The Pilo Family Circus (Australia)

It’s not everyday that a clown novel wins a literary award, but Will Elliott’s Pilo Family Circus is one that garnered multiple honors, and allowed its author to be named “Best Young Novelist” in 2007 by the Sydney Morning Herald. The novel combines classic horror with a touch of existentialism, is set in Brisbane, and follows a deadbeat named Jamie who has a heart-pounding experience: while driving home one evening he nearly collides into a clown which, after making silent, mouthing gestures, disappears into the night. Soon after Jamie is tormented by three clowns who destroy his house, leaving a message: “For a Special Guy.” Things get even creepier Jamie not only discovers the clowns’ sinister origins, but also that he is inadvertently becoming one himself.